What We Owe the Future

by William MacAskill

Basic Books

352 pp., $32.00

Oxford Professor MacAskill is going to save humanity—but he needs our help. Or at least our willingness to put aside our selfish short-term goals and let the experts decide what’s best. This is his gospel of “effective altruism,” in which he claims that technocrats using cutting-edge, data-driven science can optimize the well-being of humanity, both in the present and future.

The key to MacAskill’s plan to save our future is what he calls ethical longtermism. This highfalutin’ idea from a thirtysomething Oxford don starts with “the idea that positively influencing the longterm future is a key moral priority of our time.” He elaborates, explaining that

Longtermism is about taking seriously just how big the future could be and how high the stakes are in shaping it. If humanity survives even a fraction of its potential life span, then strange as it may seem, we are the ancients; we live at the beginning of history, in the most distant past. We need to act wisely.

Fortunately for our future progeny (though less fortunately for us), MacAskill presents a seemingly impressive blend of philosophical argumentation, historical vignettes, thought experiments, hypothetical cases, real-world prescriptions, and charts upon charts of data to argue why the long-term future matters more than the present and more than pretty much everything else.

As one might expect, the gist of MacAskill’s book is that common people aren’t competent to make decisions that will benefit the greater good—these decisions must be made for them by far-seeing data scientists. It is a worldview that is deeply disturbing on many levels and totalitarian in its implications. It is the exact book one would expect from a cloistered academic who fantasizes about having the power to run the world. MacAskill’s intellectual hubris, which drips from nearly every page, is by turns comical and alarming.

MacAskill’s thought is a species of consequentialism, which is an ethical system in which the morality of an action depends upon its outcome. As such, his reasoning suffers from the same general objections as all “greater good” consequentialist reasoning. Namely, it is nearly impossible to objectively measure the good based on outcomes—what is good to some may be bad to others. Furthermore, the idea that we can accurately forecast the results of our actions is dubious, even with the most advanced data analysis available.

More importantly, MacAskill inexcusably dismisses deontological ethics, or the idea that actions are moral or immoral in and of themselves without relationship to their outcomes. Virtues, and duties to family, friends, and countrymen, are left out of the equation.

Even if consequentialism were somehow viable, MacAskill does not explain why his particular version and his particular predictive models take primacy over other competing ones. More broadly, why should we care about consequentialism, future persons, or morality at all for that matter?

In the book’s first part, MacAskill attempts to lay out his moral argument for longtermism. Here he moves from the commonsense assumption that “future persons count,” to the argument that future persons over the long run should count much more significantly than we commonly assume. After diffusing anticipated objections appealing to partiality and concern for one’s contemporaries (such as friends and family), MacAskill moves on to argue for the importance of the aggregated well-being of all of future humanity.

Before one can doubt whether such a vast abstraction can be accurately measured, MacAskill conjures the spectre of cataclysm. Humanity is at a precarious point in its history. What humans do now will have resounding effects, both positive and negative, for the entirety of future civilization. Citing historical examples of Quaker abolitionists and early feminists, MacAskill argues that we are in an analogous situation and are duty bound to change the status quo. He presents the reader with a varied and detailed list of doomsday predictions and existential risks ranging from engineered pathogens, to a world war between the great powers, and civilizational collapse from fossil fuel depletion, climate change, falling fertility rates, and economic stagnation. With this vast, weighty, and utterly terrifying list of eschatological prophesies, MacAskill further hammers home the theme of immanent existential risk if humanity doesn’t make well-informed decisions to promote its future aggregate well-being.

As if the future of humanity wasn’t a weighty enough problem, MacAskill also makes the case for why our present moral calculus should take into account not only the predicted aggregated well-being of future humans but the predicted aggregated well-being of future nonhuman sentient life, too. And as a secular humanist, MacAskill accepts the inherent goodness of progressive politics, feminism, gay rights, and access to abortion. All of these views are somehow related to mechanically employing math and science to moral decision making.

As such, data-driven technocrats should run the world’s governing organizations and use political and bureaucratic influence to promote longtermist aims. MacAskill dreamily concludes by stating “there’s no better time for a movement that will stand up, not just for our generation or even our children’s generation, but for all those who are to come.”

Troubling dangers abound in MacAskill’s longtermist vision. First, such a view provides a convenient justification for both individuals and organizations to ignore their more immediate duties to family, friends, community, and fellow citizens. As a former Oxford philosopher myself, I too was once caught up in a worldview similar to MacAskill’s. Given the apparent severity and immediacy of the world’s existential problems, I flattered myself with a heightened sense of my ability and purpose as an intellectual to solve them.

The hubris of the would-be class of world-controlling technocrats makes them inconsiderate, irresponsive, and contemptuous of their fellow humans. Any obstacle to longtermist solutions can justify any repressive act whatsoever, no matter how heinous, irrational, or absurd, as long as it can be justified as part of the greater good. We should warily eye every theorist, organization, and movement that justifies its actions as benefitting all of future humanity. Such utopian promises lead to corruption, hypocrisy, and abuse, despite their good intentions.

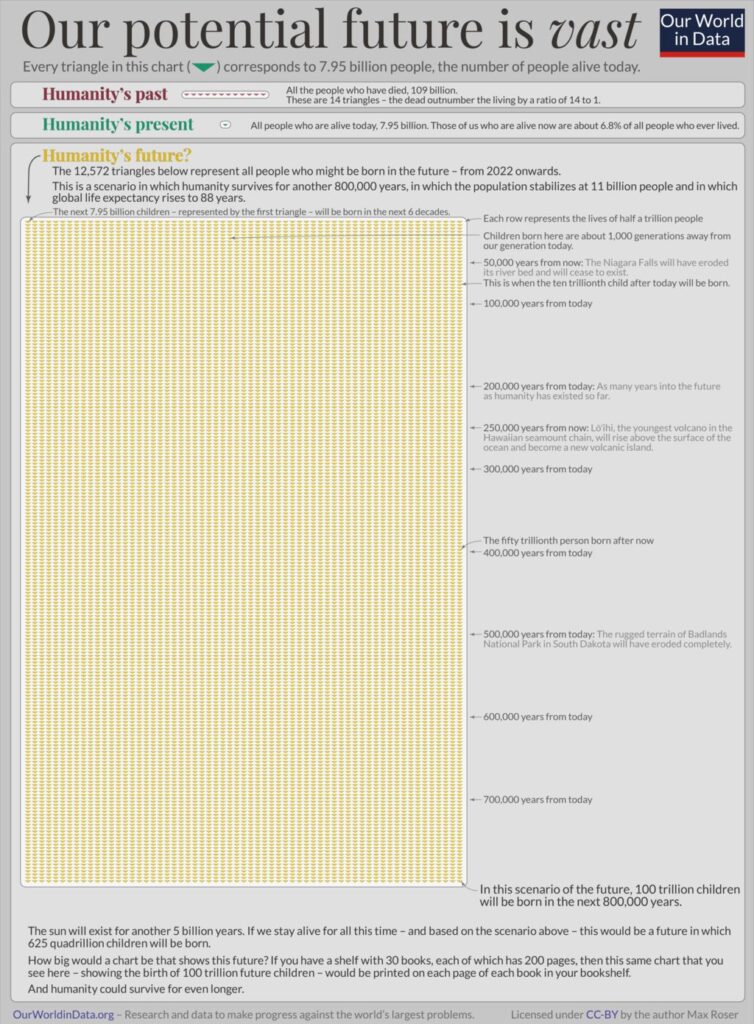

Each small triangle represents 7.95 billion people.

(Max Roser / via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY)

Sadly, this book’s popularity, along with the popularity of the “effective altruism” concept more generally, reflects today’s deep and persistent spiritual bereftness. Having fully dismissed both God and his laws, the modern, secular mind rushes headlong to refill His absence with inadequate man-made artifices and contrivances. Despite the complexity, sophistication, and cleverness of MacAskill’s ideas, there is no doubt that absurdity, ugliness, and evil will follow from their implementation.

There is still time left to rescue the past, present, and future from MacAskill’s ideological future savers. Effective Altruists must consider the real world beyond their charts, spreadsheets, and maximin utility calculations. MacAskill and his acolytes must exercise some much-needed self-reflection and humility and then repent for all the damage that they’ve caused thus far. Heck, if I, a former Oxfordian caught deep in his ideological grasp could do it, then there’s hope for them as well.

After repenting, they should get to work on disassembling the Frankenstein monster they’ve unwittingly created. Then they can move on with their lives to begin doing human things in the present. Instead of saving a theoretical world that doesn’t yet exist and may never exist, they could start a family, open a small business, connect with their roots, volunteer at a soup kitchen, plant a tree, or take up beekeeping. Anything would be better than trying to save everything all the time. And while they wouldn’t get the same rush as they would from saving the totality of future humanity, the newly-enlightened might nonetheless come to discover that they’ve made their little corner of the world and the particular people in it a little bit better off by performing such boring, mundane, and simple day-to-day acts. In so doing, they would come to realize just how much they owe to the friends, family, and community who made them who they are and, after that, what they owe to God.

Leave a Reply