Let’s say that a state passed a statute proscribing teachers from teaching reading in a language other than English until the student had passed the eighth grade. Violation of the statute was a misdemeanor. The state’s rationale was to assure that immigrant children learned English and assimilated. In fact, the state declared that teaching immigrant children in a foreign tongue “was inimical to [the state’s] own safety,” adding, “the English language should be and become the mother tongue of all children reared in this state.”

Let’s further suppose that a teacher defied the law and taught reading to an elementary-school student in his native German. The teacher was convicted and appealed, citing the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution: “no state . . . shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” The state might then invoke the Tenth Amendment: Powers not delegated to the federal government nor prohibited to the states are reserved to the states or the people. School curriculums are not areas of federal power, it would argue.

Let’s further suppose that the teacher’s appeals were unsuccessful, even at the state’s supreme court, which held that the law represented the state’s proper application of its power over the health and safety of its citizens. The teacher appealed to the United States Supreme Court, again invoking an interest in liberty under the Fourteenth Amendment. Again, the state invoked its police powers in its defense.

How should the Court approach the case in order to reach the right answer? The answer for Justice Antonin Scalia was originalism: the idea that “the meaning of a constitutional provision is fixed at the time it is adopted and it cannot be changed through judicial interpretation.” Scalia believed that every legal question had a correct answer and that originalism and textualism, the doctrine that the words in legislative enactments should be given their ordinary meaning at the time they were passed, would reveal that answer. In his new book, The Justice of Contradictions: Antonin Scalia and the Politics of Disruption, Richard Hasen, Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Political Science at the University of California, Irvine, examines how well Scalia’s theories worked in practice. Do the neutral principles of originalism and textualism produce the proper legal result when applied? His verdict: Without a lot of fudging, they do not. That verdict seems fair.

Back to the Germans. To apply textualism, we need to know what the Fourteenth Amendment means by “liberty.” Fundamental liberties, the Court has written, are those freedoms that “are deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition” such that “neither liberty nor justice would exist if [they] were sacrificed.”

So if we put our facts about the teacher and the German student into Antonin Scalia’s neutral decision-making machine, what answer comes out? Federalism or freedom? As this exercise has shown, and as Professor Hasen makes clear throughout his book, originalism is not very workable, which is why Scalia himself inconsistently applied it. In fact, the teacher, Robert Meyer, prevailed against the state of Nebraska on these facts in 1923. The United States Supreme Court made its decision not by applying principles of originalism but by conjuring up the horrors that seven-year-old boys endured in Sparta when separated by the state from their parents. So the Supreme Court chose liberty over federalism. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

Nearly 100 years later, thanks to the Supreme Court, we have a lot more liberty—or at least some people do—and a lot less collective say about governing our communities. As the legal scholar Erwin Chemerinsky has noted, the Supreme Court has for some time safeguarded the right to marry, the right to control the upbringing of children, the right to procreate, and the right to engage in homosexual activity, “even though these liberties are not mentioned in the Constitution and were not intended by the framers.” Why should the right to use cocaine be treated differently? Why not indeed? We are all familiar with that famous tenet of constitutional interpretation, “In for a dime, in for a dollar.” This ratchet effect continues to drive constitutional decisions.

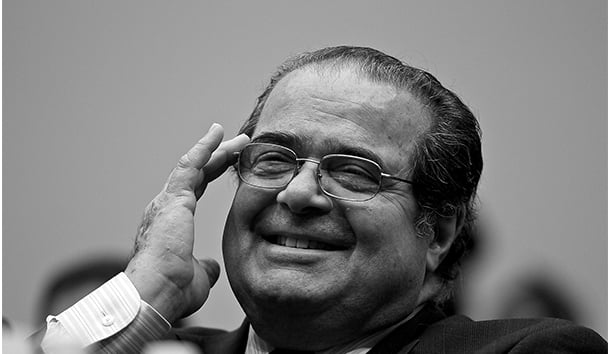

As has been clear for awhile, the Constitution has become the house that Jack built on a pile of sand. The problem for conservatives is that “liberty” has become a runaway train, with no hard definition and no brakes. For decades, we were without principled means to defend our communitarian and moral concerns against its invocation. Associate Justice Antonin Scalia became our voice.

Professor Hasen efficiently covers a lot of ground in this informative and generally fair presentation of Scalia’s contradictory jurisprudence. His point is not that Scalia was more inconsistent than his colleagues, or even more oriented toward results. Rather, Hasen corrects the impression that Scalia himself projected of having developed a foolproof formula for getting the right legal answer every time without regard to those results. As Richard Posner and others have demonstrated in their critiques of Scalia’s embrace of textualism and originalism, these vary. Methods of interpretation compete. Facts are messy. Consistency is, frankly, impossible. Scalia’s self-admitted inconsistency in applying textualism and originalism comes from competing but acknowledged means of interpreting constitutional and statutory provisions, such as stare decisis, to which he adhered selectively; to the rule of lenity (when statutory interpretations appear equally valid, the criminal defendant prevails); and to the avoidance of absurd results. Mix it all together, and Justice Scalia was left with considerable flexibility in his approach to cases. In general, this flexibility redounded to the benefit of his preferred outcomes. And as the author notes in asides, originalism has become as flexible a concept as liberty. Scalia, for example, declared that originalism compelled the result in Brown v. Board of Education; a laughable remark, for, as Richard Posner has noted, had the public understood the Fourteenth Amendment to require school desegregation, that amendment never would have passed. More recently, conservative scholars have posited that originalism compelled the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage decision, a truly imaginative theory that one must charitably attribute to self-delusion. One is reminded of the line in Cyrano de Bergerac, where the hero justifies his deceptions by musing, “After all, a lie is a kind of myth, and a myth is a kind of truth.” It is also the case that Scalia was not above virtue signaling, denouncing the correctly decided Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 Supreme Court case that held constitutional an executive order temporarily banning Japanese living in the United States, including U.S. citizens, from certain West Coast areas after Pearl Harbor.

This brings us to Professor Hasen’s subheading—Scalia as disrupter. Hasen suggests that the Supreme Court’s fall in public esteem might be owing to Scalia’s vitriolic dissents and sarcastic communications. He even provides silly charts revealing Scalia’s energetic public-appearance schedule. The Justice accused his colleagues not just of error but of bad faith, toadying to elites, and truckling. Hasen’s point is not that Scalia was wrong to criticize them, but that Scalia was no better than his fellow Justices in manipulating his opinions to obtain the result he desired. His barbs, therefore, were nasty, hypocritical, and unprofessional.

Well . . . whatever. We Scalia admirers did not love him for his consistency or his good manners. We loved him for his intellect, his insights, and his courage. As we in the provinces saw the Supreme Court turn criminal behavior into constitutional rights, for example, or diminish our allowed roles in our communities, we could only retreat, watch, and worry. After all, we had families to raise and livings to make. We feared the repercussions of fighting back. Perhaps we really were the mean-spirited hayseeds that Supreme Court majorities identified in rejecting the results of our political will. Scalia did not start these conflicts. In fact, his declamations were nearly always responses to majority provocations. But with his wit, intellect, and flourish, Antonin Scalia assured us we were not crazy, and in an attention-getting style that made us smile. Perhaps we, too, had legitimate interests—maybe even rights. In fact, the most compelling parts of this book are the long, impassioned passages from Justice Scalia’s dissents. Who can forget his characterization of the majority opinion in the same-sex marriage case as “cooing”?

Will there ever be another Antonin Scalia? Certainly, it is hard to identify a successor. Hasen suggests the Federalist Society as a possible source for one, but optimism on this score is unwarranted. The Federalist Society is split between the libertarians and the paleoconservatives, and business interests put up the funding. Should it supply libertarian justices to the Court (and the courts), we are likely in for deregulated industries, open borders, and no-fault crime, none of which would have appealed to Scalia. These new freedoms will be celebrated in the name of liberty. And we the people will have had nothing to say about them.

The Justice of Contradictions: Antonin Scalia and the Politics of Disruption, by Richard L. Hasen (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) 248 pp., $30.00

Leave a Reply