Donald Rumsfeld has produced, four years after his departure from government, a memoir of no stylistic distinction. It contains few if any interesting revelations, save, perhaps, those relating to President Nixon’s choice of vice presidents. For what it does contain, it is at least twice as long as it should be. There is a great deal of not particularly subtle score-settling, the principal targets of which are Colin Powell, Condoleezza Rice, George H.W. Bush, and Richard Armitage. The superficial reader will find the book to be a fairly interesting narrative by an important and more than ordinarily outspoken actor who both gave and received the usual blows of politics. More informed readers will view it as, at best, a “modified, limited hangout,” which is at important points an exercise in mendacious concealment and occasional outright lying, and which betrays an attitude that seriously threatens the American constitutional order and whatever prospects exist for order among nations.

One will learn nothing here of the writer’s intellectual formation. Donald Rumsfeld is the self-confident, industrious, and ambitious son of a realtor in the Chicago suburbs. He says scarcely anything of his passage through Princeton with the aid of an NROTC scholarship. Unlike his prep-school-educated contemporaries, he was insufficiently prepared to be excused from required courses. He led the wrestling team and majored in government. In retrospect, he regrets not majoring in history, an appropriate reflection and a regret he shares with another actor in the Iraq imbroglio, Tony Blair. The only professor he deems worthy of mention is a left-winger whom he criticizes for disparaging private enterprise.

Rumsfeld is a child of the Eisenhower era who took for granted American omnipotence and supremacy in a world in which the other great powers had bombed each other to smithereens. Unlike the mature statesmen of that era, he was unscarred by the Depression and by America’s defeats and military inferiority in the first year of World War II.

He is to be commended for publishing, together with his book, a website (www.rumsfeld.com) containing numerous documents declassified at his request, most of which would not have otherwise seen the light of day for many years to come. Rumsfeld views these documents as helpful to his reputation; they are anything but.

The most significant revelation in this archive, and the most serious elision and misrepresentation in the book, concerns Rumsfeld’s campaign to modify the Posse Comitatus and Insurrection Acts so as to give the military the authority to arrest U.S. civilians in the United States. This began with a note to his old friend and Ford-administration colleague Vice President Richard Cheney in May 2001: “the pretense that posse comitatus prevents us from being engaged except in a support role will drop by the wayside at the first sign of an attack.” The note was followed by a memorandum, dated October 23, 2001, from the ever-helpful John Yoo, upholding military arrests. In May 2002, President Bush’s Homeland Security Strategy included a requirement to conduct “a thorough review of the laws permitting the military to act within the United States.” This prompted a memorandum of July 24, 2002, from the general counsel for the Department of Defense, William Haynes, declaring, “If an enemy of the United States is located in the United States the President may direct you to employ the Armed Forces of the United States against such an enemy.” In October 2002, Rumsfeld sent a memorandum to Haynes, Paul Wolfowitz, and Douglas Feith asking for a study of posse comitatus. Then, in September 2005, following Hurricane Katrina, he directed a memorandum to Gen. Dick Myers urging that

DoD [be] the lead agency for “catastrophic events”—natural or terrorist . . . DoD personnel, preferably Guardsmen, but not necessarily only Guardsmen would be permitted to engage in law enforcement activities consistent with law . . . The NORTHCOM commander . . . would become the principal USG officer for that ‘catastrophic event’ and relevant FEMA and Coast Guard elements would report to him . . . The USG and DHS will need to focus on the reality that state and local governments are uneven in capabilities, sometimes politicized, and prone to spend funds in areas that are of interest from their own perspectives, and not on what the federal government needs them to fund.

As a blueprint for military dictatorship, this puts the famous Huston Memorandum of the Nixon era in the shade.

From this memoir one would gain the impression that Rumsfeld was a voice of restraint in supplanting state-government authority. He declares that the decision not to do so at the time of Katrina was a correct one. (He does not concede that it was constitutionally required.) For good measure, Rumsfeld includes in his archive a note describing the modification of posse comitatus as “a solution in search of a problem.” Nowhere does he disclose that the Department of Defense during his own tenure caused a “stealth amendment” to be included as Section 1076 of the Defense Authorization Act of 2007, effectively nullifying posse comitatus, which was repealed in the following year only because of a letter of protest dated August 6, 2006, and signed by all 50 state governors (including Jeb Bush, Mitt Romney, Mike Huckabee, Haley Barbour, Tim Pawlenty, Jon Huntsman, and Mitch Daniels). The memoir also refers to arrests by the FBI of Yemeni Americans in Lackawanna, New York, without disclosing that Cheney, at least, wanted the military to conduct the arrests, before being restrained by Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, FBI Director Robert Mueller, and others.

Another interesting omission relates to the so-called torture memorandum. Rumsfeld devotes an entire chapter to his crocodile tears over the lack of a detention policy, which he thinks should have been forged by the NSC Deputies Committee presided over by Condoleezza Rice. Instead, he acknowledges, “Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz eventually encouraged a group of senior officials from across the government to hold ad hoc deputies-level meetings to address detainee-related questions outside the formal NSC system.” He does not tell us that some of the decisions resulting from this process were approved by the President without the usual interagency review and with the complicity of the Vice President and the White House counsel’s office, nor that the State Department was excluded from the process, leading to a famous and explosive memorandum from its general counsel, William H. Taft IV, himself a former acting secretary of Defense. The only reference to Taft in the memoir appears when the author tells us that Taft agreed “that al Qaeda or Taliban soldiers are presumptively not POWs.” Taft’s conclusion that they nonetheless are entitled to the protection of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention is unmentioned. (It is unlikely that Taft will have this distortion of his expressed views brought to his attention since, inexplicably, his name is omitted from the book’s 22-page Index.)

Elsewhere, Rumsfeld names several service secretaries who did not dissent from Department of Defense detention policies; he fails to mention the fact that all three service judge advocates objected to these policies. We learn that the International Red Cross had access to Defense Department detainees; no mention is made of the denial of access by the Red Cross to CIA detainees. Rumsfeld invokes the Supreme Court’s decision in Ex Parte Quirin as demonstrating the propriety of executive detention and the use of military commissions, while ignoring that the Supreme Court itself provided judicial review by habeas corpus. He criticizes the Court for its invalidation of various provisions of the Military Commissions Act, which, we are told, “created various avenues of judicial review,” without adding that the act attempted to bar Supreme Court jurisdiction by constituting the politically sympathetic Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit as the final authority.

Rumsfeld notes Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson’s approval of executive detention abroad in the Eisentrager case, yet nothing could be more foreign to Rumsfeld’s policy than Jackson’s statements in other cases: “[M]en have discovered no technique for long preserving free government except that the Executive be under the law, and that the law be made by parliamentary deliberations.” “[E]mergency powers are consistent with free government only when their control is lodged elsewhere than in the Executive that exercises them.” “[P]rocedural due process must be a specialized responsibility within the competence of the judiciary on which they do not bend before political branches of the government, as they should on matters of policy.”

Rumsfeld, quoting Bryce Harlow, expresses great fear about “the erosion of executive power.” He blames the change on a new world of judicial activism, instancing abortion, gun rights, and campaign-finance cases. But, as Jackson reminded us, there is nothing new or illegitimate about judicial concern with personal liberty—with freedom from arbitrary confinement by the executive. Both Merryman and Milligan were decided 150 years ago; Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the remonstrances of the Declaration of Independence do not evince enthusiasm for unconstrained executive detention of citizens. “What was the alternative,” Rumsfeld asks, “—letting them go and then hoping to catch them as they were committing the next terrorist attack against the American people?” The alternative was that which was followed by the British courts and government: statutorily authorized brief detention followed by judicial review, and the acceptance of releases as a normal part of any judicial system.

An equal lack of humility appears elsewhere. “After a few in the CIA alleged that some policy officials had ‘politicized intelligence’, I asked not to receive my daily oral briefings from the CIA”—supposedly out of fear that any questions he asked might be misconstrued. Rumsfeld voices skepticism about the wisdom of creating the Directorate of National Intelligence; he does not acknowledge his refusal to cooperate with it by allowing the assignment of DIA agents to other agencies, nor his creation of an assistant secretary for intelligence within the Department of Defense.

He treats with derision the requirement for approval of hostilities by the U.N. Security Council—“not a necessary precursor to military action”—and alludes to “a Bush doctrine of pre-emption” as, “more precisely, anticipatory self-defense.” This is no service to Bush’s reputation. In presenting the case for the Iraq intervention to the United Nations, our U.N. ambassador carefully avoided reliance on any such doctrine, alleging instead Iraqi breaches of earlier resolutions relating to disarmament. The Security Council approved the Gulf War, the cost of which was borne by allied nations, including Germany, France, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. (By contrast, the never-approved Iraq war laid its entire cost, said to be a trillion dollars and counting, on the United States and Britain.)

There is astonishingly little concern in this work for the military as an institution. (Rumsfeld has nothing to say, for example, of the programs of the military academies and war colleges.) One may suspect that a contributing cause of the Abu Ghraib scandal in Iraq and similar recent events in Afghanistan is the recruitment of the volunteer army from among the poorest American communities. But if Rumsfeld has any ideas for creating a more representative military (shorter tours, direct commissions or promotions for enlistees with needed specialties in sciences, medical care, or exotic languages), they are not presented here. Rather, he treats the military as an instrument that will not break, despite the arbitrary prolongations of enlistments and battlefield tours and the stripping of the state National Guards to reinforce the Army overseas.

Rumsfeld had at his disposal a trillion-dollar military and a $50 billion per year intelligence establishment. In the run-up to the Iraq war, the present reviewer, responding in a letter to the London Spectator of April 5, 2003, to Richard Perle’s derisive treatment of the U.N. Security Council, observed that, “if there is conceit, it is on the part of those who believe that powers have ceased to be powers and that infantry is no longer important in war.” Andrew Bonar Law, in rejecting British intervention in Turkey in 1922, declared of Britain, “we cannot alone be the policeman of the world.” That decision preserved British power for another generation and assured Turkey’s sympathy in World War II. America has yet to find her Bonar Law.

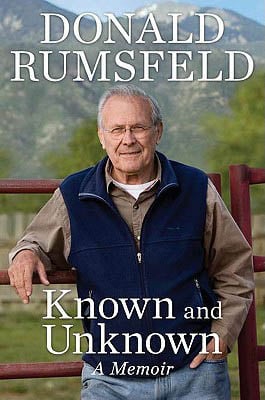

[Known and Unknown: A Memoir, by Donald Rumsfeld (New York: Sentinel) 832 pp., $36.00]

Leave a Reply