All literary genres have their loyalists, but few have more devoted—and querulous—readers than the Western. So when in the mid-1980’s rumors began to circulate that Larry McMurtry, hitherto known for his angst-ridden tales of modern Texas, was at work on an epic oater, shoot-’em-up fans began looking for a noose, sure that the bespectacled belletrist would revise their Old West out of existence. He did; but McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove went on to become one of the best-selling Westerns of recent times. Of course, diehard oatereaters had their day with it; they even convened a special panel at the 1985 Western Historical Association convention to squabble over why the mock-heroic cowboys who populate the novel needed to drive their cattle all the way to Montana when they would have hit a stockyard-bound railroad line in southern Kansas. In Lonesome Dove McMurtry took pains to strip away the legendary West, to discover a region plagued by genocide, random violence, failure, and frustrated dreams, a West where many lose while few gain, where people travel far to go nowhere.

Sequels never quite match up to their progenitors, and McMurtry’s Streets of Laredo is no exception. Partly, this is the inescapable result of its setting. Texas has quieted down since the hellraising days of Augustus McCrae and Woodrow Call. In Lonesome Dove, the protagonists were retired from the Texas Rangers and happily settled into a life of hard drinking and cattle rustling, ending with McCrae’s death far from home. The second book finds the fast-aging Call at loose ends, adrift in the place he helped settle. His friend, the historical figure Charles Goodnight, describes the situation, remarking of his ranch-hands:

The cowboys wore guns from wistfulness. . . . They wanted to feel that they were living in a West that was still wild. It was harmless nostalgia, for the most part; as long as they didn’t injure themselves or the livestock, he put no strictures on their use of firearms. But the Panhandle was no longer the wild West—not by a long shot. The cowboys could play or posture all they wanted to, adjusting their holsters and practicing fast draws. The fact was, they were herdsmen, not gunfighters, and it would be colossal bad luck if their herding ever brought them into contact with a real killer, of the sort that had once been common in the West.

Such psychopathic killers may have dwindled in number, but the deeds of one of them helps to propel Streets of Laredo. Across the border in Mexico, a teenager named Joey Carza has discovered that he enjoys wasting most of the people who cross his path. Had he stayed put in Ojinaga, the good gringos across the way would not have minded this antisocial behavior, but Joey has taken to crossing the line, killing whole train crews, and felling innocent men with a long-range rifle just for the pleasure of practicing his aim. In one particularly gruesome scene, the bandido slaughters a hapless cowboy and deposits choice bits of the buckaroo’s body atop the sheriff’s desk in the nearby Presidio jail, inches from the snoring lawman. When Garza unites with the racist bandit John Wesley Hardin, it is only out of expediency; their common front will earn him enough money to return to Mexico, live in high style, and mutilate his neighbors whenever the fancy strikes.

Psycho or not, Garza is the most interesting character in the novel. Woodrow Call, who should hold center stage, has always been a one-dimensional character, without much to say and without many thoughts in his head. Call, loyal as a bloodhound, is good for killing, but even being whittled down bit by bit over the years fails to inspire him to much reflection. Garza, on the other hand, actually feels passion for his line of work, sinister though it may be, and is the only character who might be said to possess an idea. The taciturn Call (“I ain’t a lawman. I work for myself.”) naturally has to go up against Garza, inspired not by noble thoughts but rather by a bounty offered by a railroad tycoon. Call suffers all kinds of setbacks, and only the help of his trustworthy sidekick Pea Eye saves him from winding up any worse than he does.

Devotees of the Western genre will find little to displease in Streets of Laredo. McMurtry peppers his story with enough historical characters to keep diehards guessing and uses his considerable literary skills to elevate his story far above the average oater, bringing in some of the dark vision that makes his earlier modern novels like The Last Picture Show so compelling. As he remarks of the people of the borderland, “Survival was all they had time for, and numbers of them failed even at that.” His sequel is not, and probably could not have been, the great achievement of Lonesome Dove, but far weaker attempts have been made at getting to the heart of the West than Streets of Laredo.

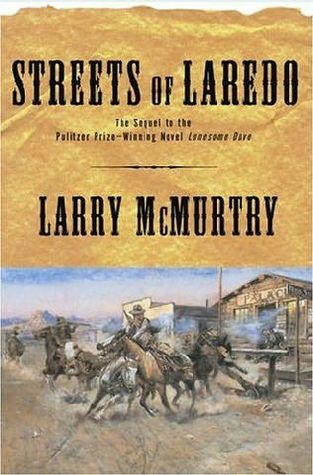

[Streets of Laredo, by Larry McMurtry (New York: Simon & Schuster) 864 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply