Paul Johnson’s book Intellectuals, published last year, chronicles the transgressions of modern avatars of wisdom (among them Rousseau, Marx, and Sartre) who, while professing a fervent devotion to humanity, behaved inhumanly toward those most meriting their compassion—spouses, lovers, family, friends, and associates. Although the targets of Johnson’s caustic pen all were idols of the left, the volume would have been more credible had its author included at least one intellectual of the right. As Nathaniel Branden amply illustrates, the prophetess of laissez-faire capitalism would have been a worthy candidate. Judgment Day was written by Ayn Rand’s former disciple and intellectual agent, who for twenty years played St. Paul to her messiah, and for most of that period also played a more earthy role in milady’s boudoir.

Rand (1905-1982) was a novelist and self-styled philosopher who expounded her economic-political-moral theories in such best-selling novels as Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead, and in nonfiction works including The Virtues of Selfishness and Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal.

Had the Russian-born author stopped after defending the free market and opposing collectivism, it would have been well and good. She went much further, however, attempting to construct an ethical system based on the idea of the individual as the highest human value. Capitalism became not merely utilitarian or a matter of justice but a moral ideal. In human relationships, selfishness was extolled. Her view of government bordered on anarchy. The Randian philosophy gained adherents in the 60’s and beyond, most among callow collegians who believed reality could best be apprehended in works of fiction. Nathaniel Branden (né Nathan Blumenthal of Toronto) was one of these. While still a teenager, Branden read The Fountainhead the way a yeshiva student studies Talmud and sent a philosophical fan letter to the author. The two eventually met, and a strange, symbiotic relationship evolved.

Initially Rand was Branden’s mentor and patron; later he became her intellectual advance man, founding an institute to disseminate her ideas via lectures, tapes, and publications. Eventually, the greatest philosopher of reason since Aristotle (her own words) decided it was only fitting that the most heroic man and woman in the contemporary world should share the delights of Eros, as a complement to the communion of their spirits.

Notwithstanding that each was married to another, this superman and superwoman became lovers, until Branden tired at last of a physical relationship with a woman twenty-five years his senior and developed a serious case of the hots for a comely Objectivist wench, who was rational and heroic (also pneumatic). When Rand learned of the affair, the earth shook with her Olympian rage and Branden was cast into outer darkness: removed from his offices of trust, shorn of emoluments, and branded “irrational.” All personal association between herself and the betrayer was terminated.

Judgment Day is Branden’s belated attempt at self-justification. In it he provides an intimate view of the great woman and her court (called the “inner circle”), from which we may infer a lady who made Lillian Hellman seem positively charming by comparison—Margaret Hamilton with a philosophical system in place of a broomstick. As any who witnessed her withering contempt for questioners who challenged her during Ford Hall Forum appearances can attest, this was not a lady to be trifled with.

Casual observers could be blinded by the glare of contradictions. The exponent of reason (whose works exalted independent judgment and critical analysis) demanded cult-like obedience from her followers. Life with Ayn—the champion of individualism par excellence—included worshipful study of the master’s canon, self-criticism sessions for errant disciples, denunciations, star chamber proceedings, and expulsions (and excommunications). Like other ideological trailblazers, Rand created a secular religion—which, for a militant atheist who damned faith as “mysticism,” was quite a feat.

Her books, treated as revelation by followers, projected a self-contained world view: suffering is the result of altruism (which subjugates the human spirit) and collectivism (which enslaves man physically). Salvation lies in capitalism (with its corresponding economic and technological progress) and the liberating doctrine of rational self-interest—breaking the psychological chains of bondage to others. Only the deity could appoint the apostles of the new creed. After Branden was banished (with the malediction that he become impotent for at least twenty years, as atonement for his sins), Leonard Peikoff, a psychiatrist, became the new supreme pontiff. The punishment for heretics was banishment from the. divine presence and eternal damnation as a “mystic” (irrational), “whimworshiper” (one dominated by his desires), “second-hander” (uncritical absorber of ideals drawn from the surrounding culture) or other species of Randian apostate.

Some of her admirers have tried to excuse Rand’s quirky, tyrannical nature with the observation that she was the architect of a noble creed, who regrettably was incapable of living up to her ideals—a transparent rationalization that Rand herself would have sneeringly dismissed as an “evasion of reality” when applied to the conduct of lesser mortals. In fact, her life—a miserable, bitter, vindictive, lonely existence in the midst of fame and fortune—was the direct result of the ethos of Objectivism. Ayn Rand lived only for herself, measuring the value of others solely in terms of the benefit that she could derive from them. She was a user who exploited the blind adoration of her immature followers, relied upon her husband, Frank O’Connor, for emotional support, before coolly asking him to exit their apartment for her twice-weekly trysts with Branden.

Like secular humanism. Objectivism is founded upon the deification of the individual. By enshrining the self, it tends to rationalize human failings and exalt human appetites, which, after all, serve the greater good (the human self). Rand, worshiping the ego, became the supreme egoist: self-assertive to the point of boorishness, candid to the point of cruelty, displaying a total lack of sympathy for the frailties of others. This is the creed she championed and lived by, a remorseless dogma without room for tolerance, compromise, or compassion.

Ayn Rand did make a number of positive contributions to the political debate. Having lived through the Russian Revolution, she was an ardent anticommunist: no one was more trenchant than she in damning the evils of the gulag state. And her opposition to collectivism was unsparing. In an age of anti-heroes, of hopelessness and determinism, she made a persuasive case for free will and celebrated the transcendence of the human spirit. Her failure was the downfall of most secular intellectuals: an obsession with ideals to the exclusion of human beings, a belief in the ultimate perfectibility of humanity, an attempt to create a man-centered moral code divorced from the eternal. Her private life stands as the ultimate refutation of her philosophy, as well as proof that utopianism of the right can be as delusionary and dangerous as utopianism of the left.

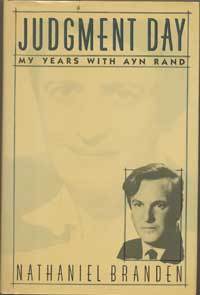

[Judgment Day: My Years With Ayn Rand, by Nathaniel Branden (Boston: Houghton Mifflin) 416 pp., $21.95]

Leave a Reply