The American poet and man of letters John Berryman created in his half-memoir, half-short story “The Imaginary Jew” what is very likely the most powerfully compressed vision of vulgar, visceral racism in our literature. In this present, honorably intended biography of Ezra Pound by an apparently Jewish and leftist professor at Queens College (whose previous books have dealt with Beats and radicals), we will not find that Pound the anti-Semite, whom Berryman visited regularly in a federal madhouse, told many, including Berryman himself, that he considered “The Imaginary Jew” a masterpiece. Nor do we learn of Pound’s hefty personal check to Louis Zukofsky (part of Pound’s Dial award he might well have spent upon himself, Zukofsky being Jewish, Marxist, experimental, and in need), which Zukofsky chose to keep forever uncashed as a monument to artistic magnanimity.

Nor does Tytell mention that history repeated itself later when Hemingway was moved (in spite of his total contempt for the political follies that got Pound put away in the first place) to send him the last of his Nobel money—along with the medal itself!—which the novelist asked Pound to keep till he got his own. Pound returned the medal but not the check. That he had locked in Incite, in spite of his own financial need. “Hem,” he would reminisce in deep age after the novelist’s suicide, “had a gift for friendship.”

Clearly Pound did, too. He got on with more creative geniuses who could not abide one another; influenced more of them to the good; publicized, cajoled, defended, promoted, and coached more of the obviously gifted of his own time than probably any other single patron, with the possible exception of Maecenas and various Medicis—and he had no money, and they were not artists. Mr. Tytell seems honestly to believe himself when he suspects Pound may have done it all—a thousand or so pieces of correspondence, among other things, per year, over decades—out of self-promotion, though he was the least conventionally successful of the great writers of his time.

The problem is, was, and will be that Pound’s genius was of a unique sort that seemed to embrace the highest reaches of human aspiration as well as the lowest depths of human claptrap. He saw through most of the conspiracies of most of the eras of most of the great civilizations only to be suckered into one of the worst ever, right in his own time, sincerely believing the Axis were out to end Usury—the root cause, for Pound, of the collapse of civilizations through the ages—whereas it now seems entirely self-evident that it was simply its latest, worst form.

What is clear, though, is that Pound acted, in his distraught and mistaken way, to preserve civilization. One important letter to Mussolini (which Tytell takes no note of, perhaps because he appears to have only the shakiest grasp of the relevant foreign languages as well as of Pound’s actual motivation) goes something like, “For twenty years you have said you would move against the monopolies, and you still have not; you have said you would move against the gold dealers, the munitions cartel, the banks, the insurance magnates,” and so on, on and on for several amazing pages—to which Mussolini, having been a tool of precisely all those interests, appears to have made no answer, perhaps, for once, out of respect for the truth. One must ask again and again as one plows through Mr. Tytell’s almost clinically detached mosaic of megalomania, racism, and political crankhood whether he even likes art, whether the obvious contemporary smash-up of human heart, mind, soul, heritage, and will touches him at all.

But, worse luck for all of us, it’s the age that seems to have managed to embrace the highest reaches of human aspiration simultaneously with the lowest depths of claptrap. Hardly any of the artists of the first half of our century were at all sanguine about the era they were forced to suffer through and into. Now they seem, frankly, well out of it, since communism, fascism, and the present comprehensively conformist subjugation of our own heritage of respect for the individual may all equally stem from the 20th century’s self-congratulatory promotion (as defined by an international credit monopoly) of so-called ordinary people, an orthodoxy of nobodyhood and nothingness that thrives on the suppression not only of Napoleons of Poetry like Pound, but all our Jeffersons, Edisons, Einsteins, Henry Fords, and Bucky Fullers, past or to come, as well.

We all survive, average Joe, genius, and plutocrat, on the collective heritage of superior acts of intelligence, perseverance, productivity, and unselfishness. We find it convenient to refer to this as human genius. But the establishment of our time seems to have taught itself an ultimate barbarous lesson: that there is an infinitude of profit in encouraging human corruptibility. Call it Apocalypse? As soon as the parasite has killed the host, the parasite will also die.

The struggle to maintain any of the glorious and useful traditions of human genius in an age that seems so bent on enthusiastically denouncing, discrediting, and abolishing them might well have produced a certain sense of strain. In Pound’s case, this struggle led to uncontrollable wrath combined with political delusion, not entirely unlike Dante’s, who stuck several of his worst enemies in Hell as much out of spite as anything, and whose worshipful attitude toward the would-be conqueror of Tuscany might have proved as mistaken as Pound’s toward Mussolini—had Henry of Luxembourg lived.

It is worth noting, too, that Shakespeare’s evident and potentially deeply compromising involvement with Essex and Southampton might not have passed for complete political wisdom, had anyone been in a position to think about it in the intervening four centuries. (Nobody was; only very recent scholarship has been able to uncover what the Bard kept hidden.) If Timon (apparently abandoned as unproducible) had seen the light of day, one might well have wondered about its author’s soundness of mind.

As for Pound’s grudge against his native land, I note only that Melville’s going quietly mad in the East Lansingburg post office or Miss Dickinson’s agonizing secret little verses she stuffed into her mattress or Whitman’s selling pencils, palsied and alone, in the streets of Camden or Hemingway’s putting the muzzle in his mouth or Berryman’s waving and flying off the bridge above a frozen Mississippi are not events to inspire confidence in our nation’s abiding love for literary art. Nor is it easy to admire the state of mind that awards an absolute army of mediocrities for their half-century of conscious willful fellow-traveling while refusing Pound any benefit of doubt in spite of his lifelong devotion to the principles of the Founders, in spite of his admission of error, in spite of a punishment cumulatively worse than death by firing squad.

So once upon, well, a time, a little before the Age of the Hero finally came to an end, our then-greatest poet sailed his silvery voice over the blue and not-yet-polluted waters of Lake Ontario in prophetic prayer for the resumption, after civil war, of the unique destiny of Americans:

the gait they have of persons

who never

knew how it felt to stand

in the presence of superiors

. . . But unfortunately the prophecy, unheeded, coincided with the beginning of the systematic corruption of our public life (the Grant administration. Boss Tweed, Mark Hanna, on and on) that brought shame upon our first centennial. Whitman died broken, destitute, unread, a little ways across the Camden River from a seven-year-old boy, the only offspring of the assistant assayer for the Franklin Mint, whose own father had been a prominent congressman dedicated to reform of the nation’s monetary system according to the principles of the Founders and the Constitution.

This boy grew up to become far and away the most completely controversial and difficult poet of modern times, yet always a defender of our Constitution, Walt Whitman’s truest and best successor, a final heroic personality struggling, sometimes unsuccessfully, in the universal oobleck of the Age of Fools. When Pound walked “under the larches of paradise” of the arboretum of the asylum of St. Elizabeths in Washington, he walked where Whitman had walked before him, during our first national catastrophe, when the future madhouse was a hospital for Union soldiers (“Bearing the bandages, water, and sponge . . . “).

However hard Pound tried to write in the Dantean tradition of comedy and paradise, the times would permit of nothing short of Apocalypse—Apocalypse therefore discounted, especially by those happy to be living in this Age of Fools because they were instrumental in bringing it on, or because they are inadvertent beneficiaries of it. There is a third factor, of course, the unmentionable, unpleasant fact upon which democracies stumble and tyrannies ride: that most men are fools—but let it pass. For the rest of us, in spite of this underdone study of the life of Ezra Pound, there might be some meaning in The Cantos’ music, a cycle as bitter in the end as Winterreise:

In meiner heimat

where the dead walked

and the living were

made of cardboard.

We might hear, and out of shame regain, that gait we had “of persons who never knew how it felt to stand in the presence of a superior.” Otherwise it is just as well that the nation of, by, and for the people perish from the earth.

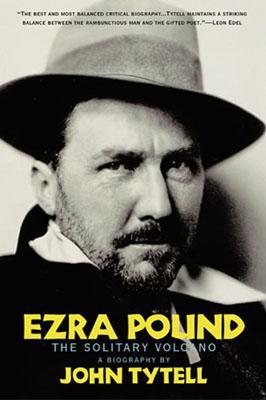

[Ezra Pound: The Solitary Volcano, by John Tytell (New York: Doubleday) 384 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply