This gathering of essays, studies, reviews, and occasional pieces is united by its subject and fused by the imagination and knowledge of the author. Clyde Wilson has responded not only to a host of opportunities as a professional historian and scholar but to sundry provocations as a lively contemporary who knows the implications of ideological distortions and of political logrolling. This Distinguished Professor has not said so explicitly, but I say that current and even emerging and future events have echoed and will echo what his sense of history has said to him, and have justified and will justify his examination of the past and its connections with the present.

Those connections are most striking not so much as deep continuities but as unaccountable absurdities. The funniest pages in this book, if these may be identified from among the strenuous competition, are those devoted to an episode in 2004 when nine Democratic presidential candidates were scheduled to appear at the Longstreet Theater on the campus of the University of South Carolina, a venue which had previously featured appearances by two presidents of the United States and a pope. Suddenly, it was discovered that the theater was named after the Rev. Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, president of a predecessor institution and others, author of Georgia Scenes (1835), defender of slavery on biblical grounds, and advocate of secession. The gathering of Democratic contenders was hastily removed to nearby Drayton Hall, the name of which not only had Old South connections but was located on streets with similarly contaminated names. There seemed to be a pattern here—a Southern pattern. The politicians were seeking Southern votes in the South, but the context had somehow to be airbrushed or gelded of all historical associations—the whole thing seemed to be more a mental-health issue than a political matter, in the ordinary sense.

So we would have to be reminded that such an inane, if not insane, episode is related to others, such as the various censorious and uninformed attempts to ban the Confederate Battle Flag from public display. The issue has its own interest, but the reaction to, or spin regarding, the “issue” is even more compelling. George W. Bush, in South Carolina in 2000, said one thing about the flag issue and later did another. John McCain tried to pander to the apparent constituency for the flag and later claimed that he had lied about it. Dick Cheney was later involved in another grotesque episode involving the Confederate Battle Flag at a funeral. Though these actions cast quite a shadow on those individuals, what is more important is a pattern that must be seen as bizarre: the repeated manipulation of Southern votes by Republicans who hold Southern people and values in contempt. This little game has been revealed for what it is for quite some time. The end of such hypocrisy is in sight, and that is going to be too bad for Republican officeholders.

Of course, there has been some fun along the way. Clyde Wilson has good reason for emphasizing the South Carolina events, but there have been other stories as well. There was a call from several directions, including from national “conservative” publications, for the correction of the Georgia state flag to the pre-1956 version. But now that the matter has indeed worked out to the old state flag, too few are aware that its design is derived from “the Stars and Bars,” the flag of the Confederate nation. Oops!

How crude the political class is, after all, and how rude the columnists and talking heads who affect to cobble together a coalition that includes Southern votes but allows nothing to Southern interests or identity or history. And that is just the point of Wilson’s essays. He is defending Dixie because she is under continual attack. Now why should that be so, so many years after Appomattox, and even so many years after the centennial of the Late Unpleasantness, and the concomitant recapitulation of Reconstruction which is now so institutionalized that Southern senators today support its extension?

After all, demonization and hatred of the South are now presented in Southern universities as Southern history, politics, and literature; since the 1960’s, the radicalization of Southern institutions has been part of a destructive, power-seeking ideology. Beating the South like a gong has been an effective political stance for a long time, and, if that were not so, then Clyde Wilson would have had that much less call to write as he has done of Southern history and culture. Covering theories and visions, politics and theory, the Revolution, the Civil War, the history of the country, the exfoliations of literature and the mass media, and the stories of heroes and rascals, he has written a book that is not for beleaguered Southerners alone but for everyone interested in what it means to be American, what it means to be free, and what it means to live in a community.

Jefferson Davis declared that the War settled the issue of the practicability of secession but not the principle, and that the issues of the constitutional crisis would sooner or later reassert themselves. He was right about that and a lot of other things as well. But to know all this, as would benefit many citizens of Boston and Minneapolis, not to mention Tuscaloosa and Biloxi, Professor Wilson’s tour of several horizons will prove of immediate and lasting value.

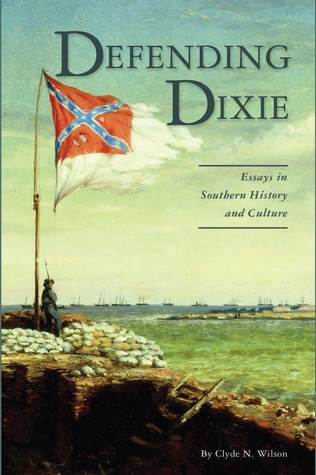

[Defending Dixie: Essays in Southern History and Culture, by Clyde N. Wilson (Columbia, SC: The Foundation for American Education) 370 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply