“Love-making is radical, while marriage is conservative.”

—Eric Hoffer

One day in the early 70’s, I read a magazine article in which Gloria Steinem was reported to have said that she would have no problem continuing her work as a writer should she ever have a baby—she’d do her writing when the baby napped. I can’t recall the date I read this, or even the year, but I do remember vividly that it was a rainy afternoon and those words about writing mothers and sleeping babies were responsible for what you could call a significant moment. For I was on that afternoon the mother of two toddlers, one of whom had avoided sleep since birth and continued to defy parental expectations, not to mention physiological law, by thriving nicely without once lying down, much less closing his eyes. And I was certain that if he ever did take a nap, I would not sit down to write. I would do instead something meaningful, something important. I would take a nap, too.

Parenthood may be the world’s biggest club, but it’s not a club without rules. And the first and most inflexible rule is: If you aren’t a member, you don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. (Which is not the same as saying that you automatically know what you’re talking about if you are a member—but that’s a different issue completely.) Gloria Steinem didn’t know what the hell she was talking about. And I had the proof—pudgy, cheerful, diapered, and sleepless—right in my own house. The knowledge of this proof was, well, liberating. So liberating that it presented, yes, a Female Option: I could completely ignore Gloria Steinem.

And now, over a decade later, it turns out Gloria Steinem is still at it. She has written a book called Marilyn: Norma Jean, in which she demonstrates that feminist thinking has changed through the years only to the extent that it has become even less connected to reality. Ms. Steinem’s subject this time is Marilyn Monroe, at first glance an unexpected choice for a feminist writer. But feminists have fallen on hard times since the glory days (people are sick of them—a definite handicap for a social movement), and the subject of Marilyn Monroe seems to offer Gloria Steinem what it offered Norman Mailer—any port in a storm.

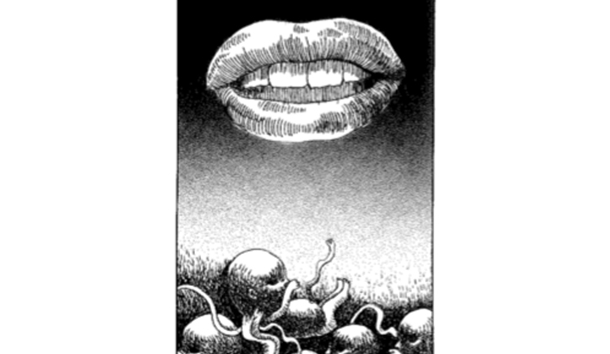

Steinem begins her “factual and emotional holograph” of Marilyn Monroe with the assumption that Monroe is a cultural “icon of continuing power,” a lasting “part of our lives and imaginations,” a woman whose “enduring” force “hook[s] into our deepest emotions of hope or fear, dream or nightmare of what our own fates might be”—in short, a “legend.” Can we stop right there? What is most interesting about this idea of Marilyn Monroe’s deep and abiding Legend is that it is universally accepted by those who write about her, and nearly nonexistent to everyone else. Steinem marvels at seeing Monroe’s likeness displayed everywhere from dress shop windows to magazine covers and cites these encounters as “everyday signs of a unique longevity.” What she actually is seeing are everyday signs of effective merchandising, and what this pervasive merchandising proves is not the strength of Monroe’s Legend but the shallowness of it. Marilyn Monroe does not “inhabit” our lives and emotions. To the degree that she exists in our “consciousness” at all, it is as a mind sketch, visual shorthand. A logo.

The notion of Marilyn Monroe’s unique and enduring grip on our imaginations has come directly from the imaginations of those who have written about her, writers who invented her Legend in order to examine it. It is significant that few of these writers are film critics, and few of the “more than forty books” about Marilyn Monroe deal specifically with her acting. (Once her “luminescence” on screen is acknowledged and her “flair for comedy” discussed, what’s left to say?) The best-known of the Monroe chroniclers are from the “cultural critic” mold, and no cultural critic worthy of the name is about to shine his light on a mediocre American actress with a flair for comedy. The Legend of Marilyn Monroe was born because she was there, once luminescent, now dead by her own hand, and they were there, the culture analysts, just popping with “perspective.” (And if the Kennedys figured in there someplace, so much the better.)

Once all the sordid details of Marilyn Monroe’s life had been revealed fully and analyzed thoroughly, these writers began repeating themselves and each other, shouting “Legend,” whispering “Myth,” murmuring “Tragedy” over and over again. And when they could repeat themselves no longer, when the mine was completely played out, they added to their books the Monroe photographs—many, of course, “never before published”—and started analyzing those. There are now available what appear to be thousands of “never before published” photographs of Marilyn Monroe, all of them blurring into one picture, just as the books dissolve into one book.

Thus, unsurprisingly, Gloria Steinem’s text in Marilyn: Norma Jean is the binder for yet another collection of seen-here-for-the-first-time photographs, pictures that are simply one more encounter with the mental outline, one more display of the logo. Still, this is one book that will never dissolve into the others.

With Marilyn: Norma Jean, Gloria Steinem has written the perfect companion to a logo: a jingle—a familiar ditty we are meant to associate with a product. The product is, of course, feminism, and this jingle is sung to the tune of “I Am Woman, See My Pain.” After ritually declaring Marilyn Monroe an “icon of continuing power” (after all, what feminist wants to hold forth on a logo?), Steinem gets down to business by asking whether, had Marilyn lived, she could “have stopped her disastrous marriages” and “kicked her life-wasting habits.” In other words, what would she have been if she hadn’t been what she was, i.e., an extremely maladjusted person; and what would she have done if she hadn’t done what she did, which was to kill herself “We will never know,” sniffles Steinem. No matter. Gloria Steinem is not seeking an answer. What she’s after here is the effect of the question. This type of self-serving nonquestion is the required groundwork, the setup, for the exemption of “cultural victims” from personal accountability for their actions and decisions.

A neglected and traumatized child, Marilyn Monroe grew into an excessive and destructive woman. What Steinem wants us to know is that Monroe was not responsible for her misspent life because not only was her childhood environment beyond her control, her adult environment was, too. If Marilyn Monroe entered womanhood with two emotional strikes against her, it was a sexist society’s refusal to offer “respect,” “support,” and acceptance of her “full humanity” that finished her off. When seen in this light, everything about the disaster that was Marilyn Monroe’s life “makes sense.”

When, for instance, she misrepresented facts, inventing what Steinem calls “parables,” she wasn’t lying, because these parables were “always consistent in emotion.” When she “ignored her own [financial] security,” she wasn’t being foolish; she was demonstrating “her emotional connection to ordinary people” and her abhorrence of becoming “one of the rich.” If she “exchanged sex for small sums of money from men she didn’t have to see again,” what counted was that she first “resisted pridefully” and “then [gave] in only when she thought there was no other way out.” Her inability to alter her distorted expectations of male-female relationships was largely the fault of her “various psychiatrists,” who “did not challenge Freudian assumptions of female passivity, penis envy, and the like.” And when she was jealous, paranoid, chronically late, and professionally nonfunctional, it was because “she felt used . . . and perhaps she was.” She was, above all, “vulnerable.” And it is her vulnerability, above all, with which other women identify.

Here, then, is Steinem’s two-pronged thesis: Because Marilyn Monroe (1) couldn’t find and wasn’t given the strength to change the course of her doomed life, she is therefore (2) some kind of metaphor for American women. This thesis captures perfectly the contradictory message of organized feminism (Your power is within you—no, it must he ceded to you by others) and the reason women by the millions avoid it. Any woman who possesses what Marilyn Monroe lacked and Gloria Steinem would give—the personal authority and dignity to live a constructive life—knows (1) that her personal authority and dignity aren’t granted or withheld by “society” and never have been, and therefore (2) the story of a movie star who lived badly and then killed herself may suggest a lot of things, but a recognizable female metaphor isn’t one of them. If a woman responds to the unhappiness of Marilyn Monroe, her response is human, not female; it is sympathy, not “empathy”; and it’s for the fact of Monroe’s unhappiness, not the price of it. But Steinem makes sympathy all but impossible by trading the real lessons of Marilyn Monroe’s life for a chance to sing the jingle, pitch the product.

If the idea of Marilyn Monroe as an identity figure for American women is bizarre, it is as nothing compared to Steinem’s account of Monroe’s “dozen or so” abortions. Even as a means of description the words are shocking. A “dozen or so”: enough to denote an accumulation; too many to be fixed precisely; an estimate. In a statement both pious and obscene, Gloria Steinem labels this pattern of ghastly, habitual destruction “an exaggerated version of most women’s struggles to control their reproductive lives.” The reason for this “exaggerated” struggle is that Monroe’s pregnancies did not occur conveniently “within a marriage and within Marilyn’s own life as an actress.” And the explanation for the bad timing is: “[O]ne can imagine her sacrificing contraception and her own safety to spontaneity, magic, and the sexual satisfaction of the man she was with.” There you have it. Marilyn Monroe had a “dozen or so” abortions because she was too unselfish for her own good. And there but for the grace of feminism go we.

As a shameless but fitting finale to this chorus of ideological excuses for personal dissipation, Gloria Steinem has donated her writer’s fee from Marilyn: Norma Jean to a “project” of her own creation, something called the Marilyn Monroe Children’s Fund. The name of this fund honors Marilyn Monroe’s “special kinship with children.” Its work will “continue something that Marilyn herself eared about.”

And logos count as legends, and babies sleep at their mothers’ convenience.

[Marilyn: Norma Jean by Gloria Steinem (New York: Henry Holt and Company) $24.95]

Leave a Reply