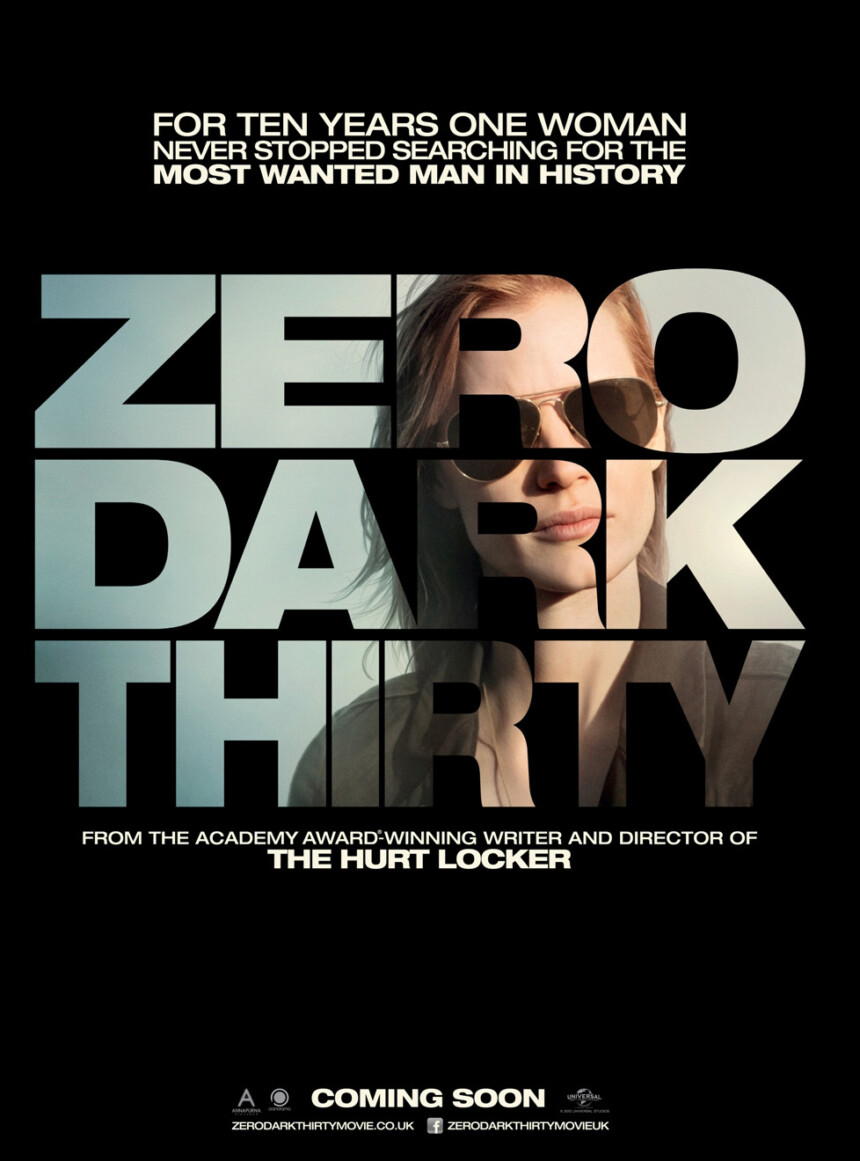

Zero Dark Thirty

Produced by Columbia and Annapurna Pictures

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Screenplay Mark Boal

Distributed by Columbia and Sony Pictures

Those who read this column may recall how impressed I was by The Hurt Locker five years ago. As directed by Kathryn Bigelow and written by Mark Boal, it still is the most honest portrayal of America’s inexcusable misadventures in Iraq.

Now Bigelow and Boal have returned with another film that attempts to depict with equal honesty our activities elsewhere in the Middle East. This time, however, their honesty is somewhat compromised, paradoxically enough, by their attempt to render actual events faithfully. The Hurt Locker was fiction based on facts; Zero Dark Thirty is fact developed with fictional tropes. Well-executed fiction can convey a sounder sense of truth than does a straightforward recounting of actual events. Among other things, the “true” story often puts the viewer at an odd remove from the events being dramatized. As scenes unfold, the question of their authenticity pushes itself between the screen and the audience. Soon we’re interrogating the narrative as we watch it. We no longer have the luxury of suspending our disbelief.

Case in point: When Zero shows us a trained CIA veteran getting herself and five colleagues blown up by making the mistake of waving an Afghan visitor through a Camp Chapman checkpoint unchecked, I found myself wondering: Could this be true? Incredibly enough, it was. In 2009, a CIA agent was so eager to meet her high-value asset that she violated protocol and signaled the perimeter gate guards to let him through without performing standard scrutiny. I may have read about this at the time, but I didn’t recall it while I was in the theater. The episode seemed so preposterous that it distracted me from the narrative. This is not to say the film is a failure. Not at all. Much of it is compelling both as fact and drama. But because so many of the “real” events it is reporting are so improbable, questions of plausibility keep popping up. We’re constantly being pulled out the film to check our memories. A writer of fiction schooled in his craft wouldn’t let this happen. He’d shape his story to give it ironclad verisimilitude.

Well, I see I’ve made a long-winded dissertation on the obstacles to effective mimesis in factual storytelling. And yet, I think it worth going into the matter because it may help to explain how the film has opened itself to grandstanding criticism from some of our officially and unofficially appointed guardians. Sens. John McCain and Dianne Feinstein have attacked the film for advocating torture. (It doesn’t.) Others have demanded hearings to determine whether or not the Obama administration gave the filmmakers unwarranted access to information in order to improve the President’s electoral chances. (Its release date was moved to after the election.) It seems our kindly watchdogs are trying to harness the film’s popularity to advance their own interests.

As if to proclaim its dedication to telling the truth, Zero begins with a raw sampling of actuality. The screen is black for the first 30 seconds, as we hear actual telephone recordings of people about to die in the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Against a cacophony of shouts, screams, and pleading, a woman’s voice emerges with clarity. She is talking on her phone to another woman who seems to be an operator at a 911 emergency call center. The first woman implores the second to send help. Her office, she sobs, has begun to catch fire; she and her coworkers are going to die. The second speaker responds with soothing professionalism: Don’t think that way; help is coming. The voices then fade out, as images take shape on the screen. It’s three years later. A ghostly pale woman stands in silence outside some roughly constructed buildings in an undisclosed desert location. She’s Jessica Chastain playing Maya, a CIA analyst who’s come to an agency black site to gain information that may further her search for Osama bin Laden, the man ultimately responsible for incinerating the nameless woman we just heard facing death in Manhattan. With this sequence Bigelow establishes the resurrection of hope from the ashes of America’s extravagant defeat at the hands of the jihadis who slammed 747s into our proud monuments of power in Manhattan and Washington, D.C. Maya is a fictional composite of two women who would spend eight years obsessively searching for Bin Laden, finally running him to ground in an unprepossessing compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, just a few blocks from the Pakistani military academy, our allies’ West Point.

Then we learn that this delicate-looking woman has been sent to watch an Al Qaeda agent named Ammar undergo torture. She meets Dan (Jason Clarke), the handsome, affable young agent who is conducting the torture, and they go inside a Quonset hut to confront the jihadi. Here, a few questions arose in my mind. Would a female analyst who looks like Chastain really be expected to witness such cruelty? It’s hardly impossible, of course, but it certainly seems improbable. A fiction writer would have prepared us for these scenes with some sense of Maya’s background and motivation. But there’s none of that here. It seems to me that Maya, whatever her reality, has been fictionally constructed to function as our surrogate. She cringes at the torture at first, and then by degrees comes to accept it. A few sessions later, her colleague leaves her alone with the trussed, naked Ammar who appeals to her to end his agony and humiliation. She approaches him a few steps as if to offer solace but then coldly tells him he can help himself by telling the truth. However imaginary this sequence, it admirably distills the reaction of most Americans to news of tortured detainees: horror, disgust, and then resignation. After all, we told ourselves at the time, if torture is the necessary means to a justifiable end, so be it.

There’s been much complaint about the torture scenes by the professionally sanctimonious in the press and in Congress. Either they haven’t seen the film, or they’ve decided opportunistically to use it as an occasion to showcase their moral superiority. Their criticisms miss the film’s point entirely. Boal and Bigelow make it clear that the torture did not work. Maya does get one piece of information from Ammar, but not while he’s being tortured. During a moment of calculated respite from his ordeal, Ammar shares lunch with Dan and Maya, and he gives her what he claims is the cover name of Bin Laden’s courier. Hardly helpful, yet Maya runs with it. And after many false starts she discovers that, even as a cover, the name is a ruse. Nevertheless, she manages to locate the courier by scouring CIA files. It turns out that he and his brothers had already been detected years before Ammar’s torture. (So much for supporting America’s brutalizing techniques.) She then locates his mother’s home. Instead of breaking in on this poor woman, she monitors her telephone line, banking on the probability that her son calls her from time to time. As it happens, he does rather regularly. Astonishingly enough, this Muslim is human. The agents shortly track him to Bin Laden’s compound.

Maya must then confront the bureaucratic indifference to her search. The CIA is presented as having ceased to worry about Bin Laden. Perhaps they took their lead from George W. Bush, who in 2007 confided to an interviewer with jolly complacency, “I really just don’t spend that much time on Bin Laden, to be honest with you.” Elsewhere, Mr. Bush told us that he never had trouble sleeping nights. I believe him on both counts, absolutely.

After the finding, Maya flies to Langley for a meeting with agency director Leon Panetta (James Gandolfini). Six or seven men enter a room, including Maya’s station director, who promptly directs her to take a seat in the back. After some preliminaries, Panetta asks who found Bin Laden. As the men dither, Maya stands and fairly shouts, “I’m the motherf–ker who found him,” glaring at the others as if to challenge contradiction. I’ve long thought the term motherf–ker had become entirely risible, as in the impolite racial joke in which a black minister responds to a parishioner’s good-morning greeting with “Mornin’, motherf–ker.” Did Maya’s real-life counterpart say it? Or is this Boal’s way of asserting Maya’s manly determination? Even if it is true, hearing it used in this scene seems, well, silly.

The film spends the better part of two hours with the preliminaries, emphasizing again and again how close we came to losing Bin Laden. A few missed details, a few uninterested superiors, and Al Qaeda’s leader might still be spinning ever more deadly plans. Finally, Maya’s pieces fit together, and her superiors reluctantly listen. At last, the mission is under way.

The film’s last 30 minutes credibly dramatize the Navy Seal assault on Bin Laden’s compound. Bigelow smartly eschews the standard action-adventure clichés. No pounding explosions, no ear-piercing heroic score. The Seals are quietly efficient. Their rifle shots are muffled; the explosives they use to blow down gates seem almost polite compared with those in a Schwarzenegger film. The final showdown ends in seconds. Blink, and you’ll miss it. Not dramatic; just real.

This brings me back to Maya, the film’s focusing lens. Her name seems chosen for its allusive suggestiveness. In Greek mythology, Maya was a daughter of Atlas, who along with her six sisters came to her father’s aid when he was condemned to hold up the skies on his shoulders. The film’s Maya carries the burden of finding Bin Laden on her narrow, small-boned shoulders, while the CIA Atlases fumble with the task. Alternately, Maya in Hindi means “illusion.” This association also seems pertinent. There is something illusory about Maya. Her sudden appearance at the film’s outset, her pale complexion, her frail body—these make her seem a ghostly avatar of the collective September 11 victims. In their name she has come to prod her associates with superhuman determination to renew their search for Bin Laden.

The narrative ends with a question posed to Maya. She’s just climbed aboard a military transport plane, its sole passenger. As tears streak Maya’s face—relief? sorrow?—the pilot asks her where she wants to go. She doesn’t answer. Instead, Bigelow is asking us through Maya where we want to go. Should we continue to provoke the Muslim world with our benighted Middle Eastern policies? Should we abandon our misadventures? Or is there another path to take? Like Maya, we’re at a fateful crossroads. Our fate depends on what we decide.

Leave a Reply