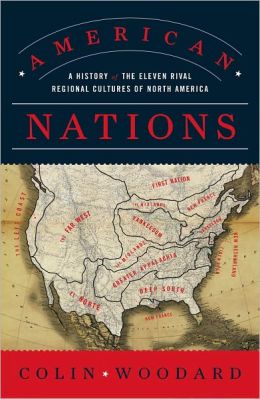

The recent flood of secession petitions in the wake of the re-election of President Barack Obama has raised secession to something more than the curiosity or esoteric joke that it has been heretofore. In the 1990’s an occasional newspaper article appeared about the League of the South or the Vermont independence movement, treating them as a harmless band of Don Quixotes or Yankee eccentrics. That was then. What is happening now is something the country has not experienced since the early 19th century: a growing sentiment among millions of Americans that they would rather their state or region separate from the mass of states and be free from a general government that many regard as tyrannical. There is no recent book more timely or prescient than Colin Woodard’s American Nations.

For readers over 40, the title will bring to mind Joel Garreau’s 1982 cult classic

Woodard’s 11 nations are Yankeedom, New Netherland (New York), the Midlands, Tidewater (Virginia and the Maryland Eastern Shore), the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, New France (Quebec and New Orleans), El Norte (Spanish New Mexico), the Far West, the Left Coast, and the First Nation (the indigenous peoples of Alaska and northern Canada). For comparison, Garreau’s eight nations were Quebec, New England, the Foundry (the Mid-Atlantic and industrial Midwest), Dixie, the Breadbasket (the agricultural Midwest and Great Plains), the Empty Quarter (the Rocky Mountain region), Ecotopia (the Pacific Coast), and MexAmerica.

Woodard argues that politics has become a struggle for power between two antagonistic national coalitions: a northern and far-western alliance of Yankeedom, New Netherland, El Norte, and the Left Coast versus a southern league composed of Tidewater, Greater Appalachia, the Deep South, and the Mountain West. The neutral Midlands currently holds the balance of power. (The recent elections suggest that the Tidewater may be shifting alliances, or becoming a second arbiter.) The balance of forces is so equal between the two coalitions that neither one is able to govern effectively. Furthermore, neither alliance is willing to compromise with the other. The result is political dysfunction and stasis.

Woodard sees no way out of our current predicament other than radical devolution. He recommends a “loose EU-style confederation of sovereign nation-states” whose powers would be limited to “national defense, foreign policy, and the negotiation of interstate trade agreements.” He points to the Articles of Confederation as a model. Under a decentralized, confederal system, he believes, the nations would be better and more happily governed, yet not sufficiently independent to go to war with one another. Without such decentralization, he foresees either secessions or the emergence of a unitary state under the dictatorial control of one coalition of nations.

Woodard anticipates, but does not really answer, an objection to his devolution scheme: the problematic existence of national enclaves within other nations, as well as newer nations that run across national boundaries like purse-skeins. An example of an enclave would be the Kentucky Bluegrass, which Woodard regards as a Tidewater colony in an otherwise Appalachian state. Another Tidewater enclave is found in northeastern Missouri, an area that was settled by Virginians and which fought for the Confederacy, but Woodard overlooks it. The Mormon West is a much larger example. It is so large, so culturally distinct, and so despised by other Westerners that it is hard to agree with Woodard’s including it in the Far West category rather than designating it as a separate nation. And what about polyglot South Florida?

African-America and Hispano-America are examples of ink-blot nations that are scattered about inside other nations. Woodard does not account for either one, yet the two constitute some 25 percent of the overall population. He also fails to deal sufficiently with the new and growing Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist immigrant nations, surmising that these foreign enclaves are being assimilated into the regional nations in which they reside. His assumption is questionable, to say the least. Are we really to believe that Somali refugees in Minnesota and Maine are becoming an integral part of Yankeedom? Or Arabs in Detroit? Or that Hispanics in the Carolinas are becoming Southerners?

Massive immigration, in other words, is a huge problem for Woodard’s model of national diversity. On the one hand, where the numbers are large, immigration is surely diluting regional identities and weakening regional loyalties. On the other, it is certainly intensifying preexisting regional antagonisms by making the biggest receiving states more multicultural and ever-more hostile to the less diverse regional nations.

Woodard’s assimilationist fantasies are necessary to sustain his belief in the possibility of peaceful, consensual devolution. We may hope that it happens, but the list of likely opposing actors is long and includes multinational corporations, the national news media, neocons, neoliberals, nonwhite minorities, the national-security complex, and so on. What’s more, the Northern nations may be no more ready to part with their erring Southern sisters than they were in 1861. Radical devolution, much more than secession, would mean the failure of the left’s postcommunist ideal of multiculturalism in one country. Since leftists see the United States as the vanguard and vindicator of a new globalized humanity, it is hard to believe they would be willing to watch while the country devolves into a loose confederation and thus see their last utopian dream perish, however false it may be.

Colin Woodard, a son of eastern Yankeedom, does not attempt to hide his cultural preference for the Northern nations, which he sees as more progressive, inclusive, and enlightened than their barbaric Southern and Western foes. His bias is such that he ascribes virtues to them that they do not deserve. For instance, he gives New Netherland exclusive credit for the Bill of Rights, when Virginia deserves equal or greater credit. He makes the preposterous claim that Yankees have fought “from the beginning” to “defend the public good from the selfish machinations of the moneyed interest,” when it was Virginia that led the opposition to Alexander Hamilton’s corrupt funding and assumption schemes, and, a century later, the Southern and Western nations who rebelled against the avaricious rule of the Northeastern plutocracy under the banner of populism. He asserts that “opposition to foreign wars . . . has been concentrated in the four nations of the northern alliance.” Yet the most catastrophic of all our overseas interventions—Woodrow Wilson’s crusade for democracy—was brought on by the bankers of New Netherland and the Anglophiles of Yankeedom.

When Woodard argues that the United States was never a unified nation, but always a federation, he has a point, while overstating his case. Before the influx of non-Western immigrants and the rise of militant atheism, Americans were united by Christianity and (with one large exception and two small ones) by a European ancestry. The states have had effective and broad-based governments in the past, never as fractured and disunited as they are today. The Jeffersonian coalition of New York, the West, and the South governed the confederacy for 60 years. The New Deal coalition, based on a similar regional alliance, did so for 50. In the 20th century, four different presidents won 60 percent of the popular vote: Roosevelt in 1936, Johnson in 1964, Nixon in 1972, Reagan in 1984. Such landslides are inconceivable today. What’s more, it is obvious that Americans (as members of rival regional nations) now hate and fear one another more than they do any foreign nation. It is not even clear what an American is anymore.

So what does the future hold? If the past is any guide, four things are certain. Regional-national differences in this continental polity are ineradicable. The multicultural project will fail. The central government will not become less corrupt or more frugal with time. Devolution and dissolution, or both, will happen one way or the other. We should learn from Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, who witnessed the tragic end of his nation in civil war and imperial autocracy, that “Mighty structures collapse onto themselves; for the gods have set this limit to growth.”

Leave a Reply