David C. Downing’s study of C.S. Lewis and his conversion to Christianity in his early 30’s offers more than the title might suggest. What we are given is not a repetition of the well-known narrative from Surprised by Joy, in which Lewis recounts his journey from youthful atheism to Christian belief 15 years later. Nor does Downing lean conspicuously on the exhaustive biographies of Lewis that have appeared in the last 10 to 15 years (for example, the widely available works of George Sayer, A.N. Wilson, and Walter Hooper). Rather, he approaches his subject’s religious life as a kind of intellectual problem, whose Christian end may have been more in doubt before Lewis’s “reluctant conversion” than the remainder of his life might lead us to believe.

Although Downing has published a previous work on Lewis, his earlier interest was in the Ransom Trilogy and in other literary products of the figure whose “journey to faith” he traces here. For Lewis, as he is understood by Downing, religious and literary truths were inextricably related. Thus, “Christianity would become the fountainhead of all myths and tales of enchantment, the key to all mythologies as the myth that unfolded in history.” Moreover, “for Lewis the incarnation became the archetype of a larger pattern, the principle of descent and reascent. In Miracles he calls this the ‘very formula of reality.’” While Lewis spoke of a specific conversion experience that he underwent in 1931, Downing points to a cumulative process of shifts that, over a 15-year period, resulted in an irreversible turning toward the Faith. Walter Hooper has described Lewis as the “most thoroughly converted man I have ever encountered.” Although Downing does not question that conclusion, he nonetheless creates a portrait of Lewis in early manhood that may cause us to marvel at such an outcome.

The most striking aspect of that early life is how much was packed into it. After losing his mother and serving on the Western Front in World War I, Lewis, an Ulster Protestant who went to Oxford on scholarship, distinguished himself as a student and teacher of modern philosophy. At a time when mathematical and positivist trends were dominant in English philosophy and when the neo-nominalism of G.E. Moore was becoming the rage at Cambridge and Oxford, Lewis was drawing his learning from other sources: the voluntarism of Schopenhauer, the evolutionary vitalism of Henri Bergson, and William James’ pragmatic defense of faith. In short, Lewis was an odd bird for an English academic philosopher; not at all surprisingly, he drifted into an intense, prolonged study of literary myth.

During this time, he frequented the magnificent poet—albeit dotty spiritualist—William Butler Yeats (a fellow Irish Protestant) and struck up a friendship with a circle of Oxford scholars who combined Christian convictions with a passion for pagan myth. Lewis’s adherence to this group (the Inklings, which included J.R.R. Tolkien, Owen Barfield, and Hugo Dyson) was fateful for his spiritual journey. The members of this circle convinced the conflicted young scholar that Christianity and pagan mythologies were not at variance: “Mythology reveals its own kind of truth and Christianity is true mythology.” In fact, “the life, death, and resurrection of Christ embodied central motifs found in all the world’s mythologies.”

Reading Downing’s chapter “Finding Truths in the Old Beliefs,” I was struck by how this drawing of comparisons between pagan and Christian stories and images decisively influenced Lewis’s return to the Faith of his childhood. Unlike an Old Testament Jew or a biblically based Protestant, Lewis was not apparently concerned about the fit—or lack of one—between the doctrines of a particular Christian church and what the candidate for conversion could accept as divinely revealed truth. Rather, he was looking to see whether Christian redemptive history could be squared with the constant elements of world mythology. His test seems to have been more literary than historical and involved Christianity’s compatibility with the ancient narratives of other cultures. I am equally struck by the range, clarity, and number of the books Lewis published or left in his estate (altogether, about 40) that were intended to be defenses of Christian belief.

Downing leaves the reader asking how Lewis’s journey to faith could result in such a multitude of brilliant apologetics. To his credit, he avoids p.r. gimmicks in dealing with the biographical aspects of Lewis’s life. He does not go into his subject’s tragic love life with poetess Joy Davidman, but he does refer briefly and unobtrusively to the successful presentation of this story in the play and movie Shadowlands. And he mercifully eschews speculation about Lewis’s alleged affairs while a young tutor at Oxford. In this case, decus may indeed be veritas.

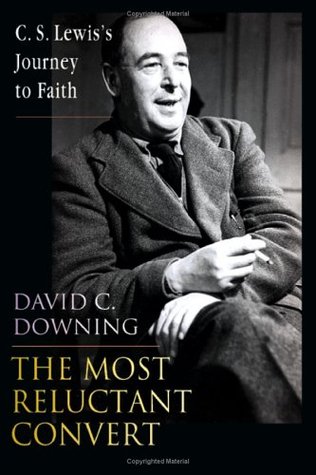

[The Most Reluctant Convert: C.S. Lewis’s Journey to Faith, by David C. Downing (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press) 180 pp., $15.99]

Leave a Reply