The American short story is moribund. The passing of giants (Flannery O’Connor, John Cheever, John O’Hara, Irwin Shaw, Peter Taylor) has relegated the form to the purgatory of academic hackdom and its innumerable ideological ax-grinders paying homage to a plethora of multicultural grievances. In the 1980’s, we had a short story “renaissance” of sorts (so, anyway, we were told) as the teacher class gave us their take on the nuances of trailer-park existence and life in the dysfunctional family. As a school, this bleak lot were known as “Minimalists” (or “the K-Mart Realists,” as Tom Wolfe branded them), taking their cue from the work of the arch-Minimalist Raymond Carver. Meanwhile, the New Yorker—despite format changes and editorial upheavals—continues to print John Updike’s and Ann Beattie’s sugary-sweet cookie-cutter tales of adultery by the pool in Connecticut. And so the short story is less and less a hot topic of conversation in our land of digital everything.

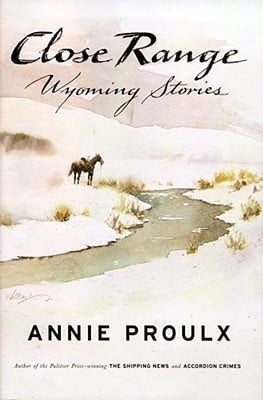

Annie Proulx, author of the Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winning The Shipping News and other works, makes her home nowadays in Wyoming, the inspiration for Close Range: a collection numbering 11 pieces, some of which appeared previously in the New Yorker, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s, most of them set on ranches “scattered like a shovelful of gravel thrown on rough ground.” Since the majority of Westerners live in cities or small towns, the possibility exists that these stories were written exclusively with Eastern readers and reviewers in mind: While most of us out here drive Subarus and Suburbans and live within sight of Safeway, the contemporary New West literati is composed mostly of carpetbaggers taking a high-horse view from the saddle. For Easterners, the much-maligned Old West remains very much alive.

Certainly, Proulx is a skilled practitioner of her art. Readers of her 1988 collection. Heart Songs and Other Stories, were made privy to the low lives of backcountry New Englanders in a land of hardscrabble dairy farms and deer hunters, where a Snopes lurks in every sugarbush. Wyoming—like Vermontis prey these days to resort development and suburban sprawl, and the juxtaposition of old and new is evident in both books. Proulx’s Vermont stories showed her very much at home in the woods and fields and in the world of physical work: Her attraction to life on the Wyoming range, with its hard climate and seasonal vagaries of weather, is palpable. She does the landscape well (“Cloud shadows race over the buff rock stacks as a projected film, casting a queasy mottle ground rash”), and has a good ear for the Southern- inflected speech of the Wyoming native.

In “The Mud Below,” a rodeo cowboy named Diamond Felts refuses to deal with the more banal realities of life and relationships by obsessively pursuing his vocation. Still young at the end of the story, though his body is a beat-up wreck from bull riding, he catches a ride to the next rodeo and realizes he has nothing in the world but memories of a few hard won and ephemeral triumphs in the arena. “People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water” is Proulx’s nod to the Gothic element in literature, a Faulkner-O’Connor parody in which the sexually misbehaved and grotesquely mutilated son of a rancher is castrated (off stage, mercifully) by the ever-present “they” concerned for the public decency. And “Job History” has the cold formality of a resume but holds up nevertheless as a man’s life and work in Wyoming unfold on the page. As a commentary on the state’s notoriously stagnant economy, the piece rings true: Leeland Lee lives in a place that just won’t give him an inch.

The Touheys are a multigenerational ranch family in “The Bunchgrass Edge of the World.” Ottaline Touhey, longing to break out of this life, is pulled back from the border of sanity by marriage to a traveling cattle buyer, only to lose her father in a small-plane crash on the ranch. ” . . . [S]tand around long enough and you get to sit down,” Old Red, the family patriarch, mentally observes.

Two “New West” stories illuminate for the outsider what it is like to live in the West of the present day. In “The Governors of Wyoming,” a young rancher, converted by an extreme Earth First! type, sells off his livestock and is abandoned finally by his mentor after getting shot while cutting a fellow rancher’s fence in the middle of the night. “A Lonely Coast” has a cast of modern Lost Generation characters who live out empty lives working dead-end town jobs and pursuing promiscuous sex and cowboy fantasies in a local bar. Like a Hollywood Western, the stor}’ ends with a nihilistic O.K. Corral-style shootout on the highway to Casper, where two people die as the result of a “road rage” incident.

The collection’s best and most controversial piece, the 1998 O’Henry Award-winning “Brokeback Mountain,” is the (at first unlikely) story of two young men—Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist—who conduct a homosexual affair while working together for a summer as sheepherders. Sheepherders usually work alone, so the story comes across initially as another strained attempt at trendy political correctness. As it develops, though, and as Ennis and Jack marry their sweethearts and raise families while periodically getting together to fish and hunt and continue their affair, it becomes apparent to the reader that their summer on the mountain was the high point of their emotional lives. Jack tells Ennis in perfect-pitch Wyoming vernacular: “You got no f——idea how bad it gets. I’m not you. I can’t make it on a couple a high altitude f—once or twice a year. You’re too much for me, Ennis, you son of a whoreson bitch. I wish I knew how to quit you.” Proulx succeeds admirably in this story of a stoic homoerotic relationship involving tvvo taciturn Old West types, comparable to such classical homosexual pairings as Alexander-Hephaestion or Hadrian-Antinous. In the end. Jack dies accidentally or is murdered (Proulx is ambiguous about this) in a ranch mishap, and Ennis is left with his memories and the credo, “if you can’t fix it you’ve got to stand it.”

Close Range: Wyoming Stories is a commendable first effort at understanding and dramatizing life in the dizzily changing contemporary American West. But if Annie Proulx has any stick-to-it-iveness, next time she’ll climb out of the saddle and drive the pickup to town for a closer look.

[Close Range: Wyoming Stories, by Annie Proulx (New York: Scribners) 283 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply