Picture this: A president, working partly through a political appointee at CIA headquarters, presses the intelligence community to come up with the “right” intelligence that this president needs to justify his actions. The president has singled out a particular foreign leader for demonization, has convinced himself that this leader is the embodiment of evil, and will not listen to dissenting opinions. The president lives in isolation in his Oval Office bubble. He is cut off from the rest of the country, surrounded by like-minded people, and derides his critics and opponents as beneath contempt. The careerist CIA hierarchy and the political appointee on the “seventh floor” at Langley are inclined to “serve” the president (that is, give him what he wants, not what he might need to make informed decisions) and choose selectively from the information they have at hand (often using dubious sources) spinning that information to give the president what he needs to justify his views and his decisions—especially when things begin to go wrong. Nevertheless, the president’s plans come to naught, and his policies fail. Yet his arrogance and self-satisfaction are such that he stubbornly clings to his version of reality, impervious to reason or evidence. This president is incapable of introspection or self-criticism.

The president is Barack Obama; the political appointee at CIA, John Brennan; the foreign leader, Vladimir Putin; and the policy, that of fomenting a conflict with Russia. A by-blow of this policy is the demonization of an antiestablishment rival, Donald Trump, who has been accused of being a Russian agent at worst, the subject of Russian blackmail at best: a stooge who is portrayed as being manipulated by the Kremlin, a portrayal based on questionable assumptions and highly dubious sources. Following its loss to Trump in the presidential election last fall, the Democratic political establishment explained its failure by spuriously claiming that the election was stolen by Moscow on its agent’s behalf, as Obama and other supporters, including their defeated presidential candidate, continued to snipe at Trump after the election and following his inauguration.

George W. Bush at least had the courtesy to shut up after he left the White House. Otherwise, little has changed in Washington or the intelligence community since then.

“W,” as John Nixon, a former senior CIA intelligence analyst who interrogated Saddam Hussein after his capture in December 2003, calls him, is smug, convinced of his own righteousness, dismissive of informed opinions, isolated, stubborn, and arrogant. (Nixon briefed the President and his advisors, including Vice President Cheney, a number of times following his return from Iraq.) As described by Nixon, Bush is by no means stupid, but willfully ignorant, a man who never reflected on his disastrous decision to invade Iraq (a decision that Nixon initially supported), and never gave much thought to the destruction that followed or to the chaos that “Operation Iraqi Freedom” unleashed. Impelled by false rumors that Saddam had planned to assassinate his father,

Bush 43 was determined to outdo Bush 41. It was almost like watching a test of strength. Whether compelling Saddam to surrender or forcing the CIA to support his efforts, Bush wanted to prove that he was a more powerful chief executive than his father had been.

Then came the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Bush now had his pretext:

The issue of Saddam and what to do about him went into hyperdrive after the 9/11 attacks. The very next day, according to White House Advisor Richard Clarke, Bush asked Clarke to find the links between Saddam and the attacks. . . . It was clear in Langley that the White House would look with favor on interpretations that supported its desire to solve the Iraq problem once and for all.

The Bush White House found its source in the Iraqi exile Ahmed Chalabi’s Iraqi National Congress, which fed self-serving and highly questionable information to an administration that was eager to hear it. Responsible intelligence officials refused to endorse the information: Iraq analysts for the CIA drafted a dissenting note on the Chalabi information, but to no avail. The dissenting opinion was “gutted,” according to Nixon, by the “seventh floor,” then transmitted to Bush by CIA Director George Tenet, another political appointee and holdover from the Clinton presidency eager to prove his worth to the Bush administration.

During his time in Iraq, Nixon found not only that Washington was ignorant of that country and of the Muslim world in general, but that it wasn’t even interested. (“Do I need to know this?” asked one administration official of a report Nixon had written on Shi’ite leaders’ clash with Sunnis after Saddam was toppled.) The focus was on finding evidence of nonexistent “weapons of mass destruction,” which the Bush White House had claimed Saddam would use against the West, including the United States (recall Bush advisor Condoleezza Rice’s ominous pre-war references to “mushroom clouds over our cities”), and on speeding up Nixon’s interrogation of Saddam Hussein, so the FBI could have a crack at him and build the case for his criminality and eventual execution.

Nixon, in his interrogation of Saddam, found that the dictator was hardly the mastermind that the Bush White House imagined; Hussein was a man who had disengaged himself from the job of managing his country. Saddam, as it turned out, had been busy writing a novel, even as the buildup for the invasion was under way. He was a wily and ruthless political operator, certainly, but a man genuinely flummoxed by Washington. Saddam insisted that he had been ready to negotiate and could not understand why the Americans should target him, a staunch opponent of Islamic radicals:

Saddam was forever puzzled by his country’s relationship with the United States. When we talked about U.S.-Iraqi relations, Saddam often got a perplexed look on his face, as if he was still trying to figure out where the relationship went wrong. “The West used to say good things about Saddam,” he said. “But after 1990 all that changed.” ( . . . The Bush 41 administration had been caught unaware by Saddam’s foray into Kuwait. I strongly doubt that if Washington had made it clear to Saddam what it was willing to do to reverse any hostile Iraqi move against Kuwait, he would have crossed that red line.) Pointing out that America had supported Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war [when, as Nixon notes, Saddam had used chemical weapons, which are clearly WMD, against the Iranians, Washington ignored it], Saddam said, “If I was wrong, why did the U.S. support me? If I was right, why did they change?”

Nixon’s book, despite devoting a central portion to the author’s interrogation of Saddam, is more about Bush than about the Iraqi dictator—and more about the United States and the flaws in her intelligence apparatus than about Iraq. Toward the end of the book, Nixon notes that Saddam and “W” were actually similar men:

Both had haughty, imperious demeanors. Both were fairly ignorant of the outside world and had rarely traveled abroad. Both tended to see things as black and white, good and bad, or for and against, and became uncomfortable when presented with multiple alternatives. Both surrounded themselves with compliant advisers and had little tolerance for dissent. Both prized unanimity, at least when it coalesced behind their own views. Both distrusted expert opinion . . . Both had little meaningful military experience and had unrealistic expectations about what force could achieve . . . Both considered themselves great men and were determined that history see them that way . . .

After becoming acquainted with both men, and having spent a number of tours of duty in Iraq, Nixon concluded that Saddam had been a “paper tiger” all along, that the war had unleashed chaos in Iraq and the Middle East, and that he—as one who had initially bought the story of a potential WMD threat from Iraq—and the CIA were all part of the disaster. Saddam was ruthless and determined, but no fanatic. As portrayed by Nixon, however, George W. Bush is a man deluded by the arrogant and ignorant ideology of universal democracy, an ideology that did not allow for human differences or for the complexities of the world as it is. Bush conscripted his religious beliefs into the service of neoconservatism. In this context, Nixon describes Bush’s farewell speech to the CIA:

He trotted out all his familiar redmeat lines . . . talking about how the future belonged to freedom. “Don’t let anyone tell you anything else. There is a God and He believes in freedom!” he told his audience. “There are those who would argue that it is OK for some people to live under dictators. That it’s just too bad and that it’s tough luck for you if you have to live in one of these societies.” Strangely enough, Bush looked at me when he made his next point: “Don’t listen to those people. Those people are eeeeeeLEETeests,” he said, dragging out the word for effect. Once again I was struck that these words were coming from a man shaped by Andover, Yale, and Skull and Bones.

John Nixon eventually left the CIA. The Obama administration proved to be cut from the same cloth as its predecessor, being full of preconceived ideas. The CIA’s “cover your ass” culture continued. Nixon offers a critique of the agency and its approach to its job. Expertise is not valued. Careerists can climb the ladder by playing the game. The agency needs fewer analysts generally, but also to develop and retain more experts. It needs to value substance over form, truth over politics.

These criticisms are cogent ones, yet Nixon stops short of addressing the real issue, which is that the United States of America, no matter how rich or how powerful, is not capable of managing the world. Nixon himself, a man who had spent years studying Iraq and Saddam Hussein, got the Iraq war wrong at first, but soon learned that there was more to Iraq than he could ever completely grasp or fully understand. How can any president, however interested, receptive, and engaged, possibly be certain of his actions regarding distant countries—alien in their culture and language, complex in their social structure—whose leaders are as ignorant of us as we are of them? The lessons of Iraq (and of our current clashes with Russia), are that more humility is in order, more thought should precede action, and Washington must recognize that it cannot solve every problem or transform every society. Taking these lessons to heart would benefit Americans, and the world. President Trump has said that he does not intend to seek to impose our values globally and that it is not our job to engage in “nation building” by attempting to transform entire societies. That is a good start, and a promising sign for the future as well.

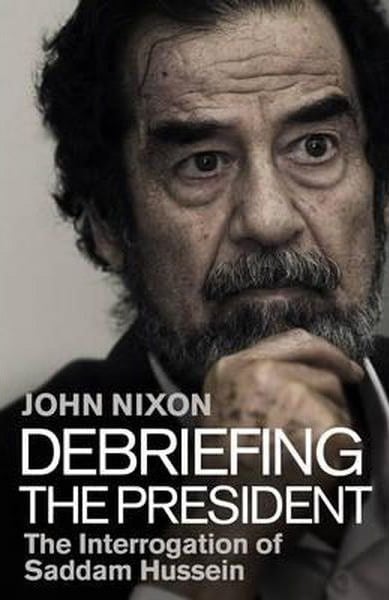

[Debriefing the President: The Interrogation of Saddam Hussein, by John Nixon (New York: Blue Rider Press) 239 pp.; $25.00]

Leave a Reply