This volume is particularly notable for readers of this journal for two reasons: First, some of it has appeared in these pages, and, secondly and more importantly, the truths it conveys have been a part of the core vision of Chronicles as, literally, a magazine of American culture. But I think too that there are certain flaws in Kauffman’s version of the essential American culture—that culture, like others, having shown contradictions we might attribute more to human nature than to political theory.

Bill Kauffman deserves much credit for the good he has done in revising some of the cliches, the received opinions that, dominating the media and the academy, have distorted our sense of American history. Going back to original sources, reading neglected texts, and rethinking old issues, he has refreshed our sense of ourselves and of our sense of nonsense. In doing so, he has stepped on many a toe, for there are a host of political reasons why convenient myths are broadcast today with religious fervor. The self-evident collapse of liberalism has exposed to everyone what a few have long known; the rationale of Big Government, if it was ever justified, no longer holds.

A primary rationale for Leviathan has been the warmaking power, which is why Kauffman has devoted much attention to the America Firsters of 1940-41. I think it is here that Kauffman, as a revisionist who has reconstituted the sense of forgotten days, has done his best work. He has revived some of the leaders of that movement as thinkers and as individuals, restoring them to our historical imagination. His treatment of Hamlin Garland and Amos Pinchot shows a background to isolationism that has roots both populist and patrician, and personal qualities that are appealing. His reconsideration of the literary side of isolationism is revealing, uniting in his view Robinson Jeffers, Kathleen Norris, Edgar Lee Masters, Edmund Wilson, John P. Marquand, John Dos Passos, Sinclair Lewis, and William Saroyan. His point is that before Pearl Harbor and Hitler’s declaration of war, America First was a rational and respectable movement that had precedence in the best American traditions as sanctioned by Washington and Jefferson—and even Hamilton— among the founders, and by widespread and thoughtful opposition to the “splendid little war” of 1898. Kauffman has made his point, and in so doing he has examined the charges of anti-Semitism that have been leveled against the America Firsters. His conclusion, based on the evidence, is to dismiss most of those charges.

Was there indeed a movement to precipitate America’s entry into the Second World War? Kauffman’s look at Anglophile Hollywood reminds us of the celebration of the British Empire that was mounted by Hollywood, and shows us that subsequent revelations by William Stephenson and Michael Korda have literally vindicated the charges brought by Senator Nye. His amusing essay on Alice Roosevelt Longworth reminds us that not everyone was reverential about FDR. His book reminds us that neither was, or is, everyone reverential about the Popular Front mentality that seems to have rewritten the national history. In such pages, and others devoted to such individualists and rambunctious reformers as the late Edward Abbey and the alive and kicking John McClaughry, Kauffman is as entertaining as he is informative.

I must say that I am less satisfied with other aspects of Kauffman’s presentation. His remarks on Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan have been already rendered obsolete by events, though I think Kauffman’s sense that there is a national grassroots movement in the direction of isolationism has much truth to it. Application of theory is contingent at best, anyway. But I cannot share Kauffman’s admiration for Gore Vidal, whose interminable rehashes of American history that everyone should know always recur to celebrating the ineffable wonderfulness of Gore Vidal, and whose fictions are either exercises in camp or, what is worse, boring historical novels that make Thomas B. Costain look like Shakespeare.

I cannot share either a related though unnecessary hostility to William F. Buckley, Jr., who, it must be said, has written the best column in this country for decades, who has been an indispensable leader of the conservative movement for those same decades, and who, more than any other prominent American in the last 40 years, has personified the once unquaint term gentleman. While I am at it, neither do I believe that there is any such thing as a “Catholic Right,” that “gay-bashing” is an adequate term for resistance to homosexual aggression, or that anticommunism was a pretext for imperialism.

On the whole, I think that Bill Kauffman’s vision of a yeoman America that looks after itself is authentic and in the best tradition of our country. But we must admit as well that there are other, baser traditions that go deep in our history —in our national psyche. Washington was tough with the Whiskey Rebellion. Jefferson—Jefferson!—precipitated Manifest Destiny and empire with the Louisiana Purchase. Who, seeing such an opportunity, would have turned it down? Why did Vermont farmboys burn houses and steal chickens in Virginia? Why did Alabama farmboys fight for independence while their leaders eyed Cuba, and more of Mexico? Americans have not resisted the masked temptation of power, and have always been contaminated by it—like the rest of humanity. Our biggest mistakes have been the subtlest ones, and insofar as they were inevitable, they were tragic.

One of Bill Kauffman’s most powerful implications is that untruth is no basis for reform. Another is that now is the time to undo the damage that has been done at home. At the end of the Cold War, we have a chance to rethink our policies—and our national mythology as well. Toward that end, Kauffman has made an important and very readable contribution.

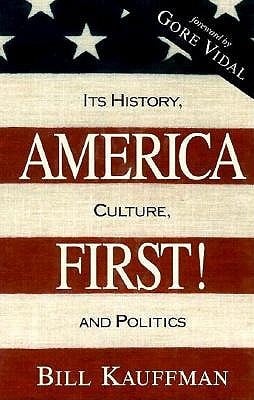

[America First! Its History, Culture, and Politics, by Bill Kauffman (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books) 296 pp., $25.95]

Leave a Reply