An untimely cold finally gave me a chance to watch The Godfather (I and II)—30 years late, but just in time for fitting juxtapositions. I spent my down time sleeping, reading news about Mexico’s ongoing narco-cartel bloodbath, and reviewing former U.S. Amb. Jeffrey Davidow’s book, The Bear and the Porcupine. Most poignant were the similarities between the Sicilian Mafia’s culture of unmitigated and ruthless violence, corruption, and paternalism and Mexico’s.

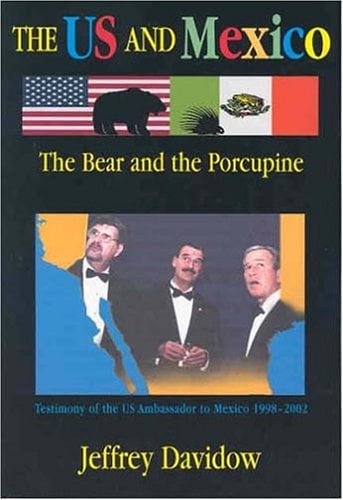

The Bear and the Porcupine is a phrase coined by Davidow to describe the overbearing tendencies of the U.S. government and the porcupine-like paranoiac defensiveness of the Mexicans toward their northern neighbors. Despite this 30-year Foreign Service apparatchik’s terminal diplomacy and conciliatory inclinations, much truth about the character of the Mexican nation comes through in his book.

This highly readable testimony is packed with back-to-back accounts of Mexican corruption, criminality, incompetence, inefficiency, and triumphant self-defeat. Davidow gathers insights not only from his four-year tenure as U.S. ambassador to Mexico (1998-2002) but through his extensive travels throughout the republic with his wife, Joan. “I learned more,” he says,

about Mexico—the dimensions of poverty and disease in the countryside, the lack of rule of law, the power of drug lords . . . the corruption of local officials . . . by moving around the countryside, talking, and listening.

Davidow chronicles his interactions with U.S. law-enforcement agencies (DEA, FBI, INS, CIA, Treasury, Customs, et al.) and the frustration he experienced from their “ingrained prejudices” about institutionalized Mexican corruption—insinuating that it is not so, while, in almost every case, verifying that it is so.

Davidow makes no bones about his conciliatory position toward Mexico, his integrationist views and fondness for the culture, and his belief in “constructive engagement.” Yet his first-hand descriptions of the Mexican government and people highlight the impossibility of positive results and, while denying the futility of U.S. engagement with Mexico, document it at almost each turn of the page. The Mexican diablo is definitely in the Machiavellian details.

Davidow asserts that “Combating the drug trade was difficult in Mexico for many reasons. The country was plagued by corruption . . . [and] a massive web of politically-motivated complicity.” In fact, he continues, “Most of the governors had no confidence in their own law enforcement officials . . . Most were absolutely convinced that . . . the Federal Attorney General (PGR) or Mexican Customs Service . . . were even more corrupt.”

The “War on Drugs” was doomed to failure from the beginning, because “every major investigation in which the DEA cooperated with the PGR was blown by well-remunerated leaks to the drug dealers from inside the Mexican government.” For example,

Mexican customs officials would pay their superiors up to a million dollars to be appointed agent-in-charge at a busy border crossing . . . the job gave them the chance to make arrangements with the local narcotics, migrant and contraband smugglers . . . the PGR was rotten with corruption.

Moreover, “Mexico’s newly appointed drug czar, Army General Jesus Gutierrez Rebollo, was arrested for being in league with the traffickers.”

There are oversights and contradictions in Davidow’s testimony, which, although raising many questions, do not detract from the merit of the whole. Whether his intention was to “remove some of [his] more outrageous statements and opinions,” as the Foreword suggests, or to cover for brazen U.S. policy blunders, or simply to keep from burning his bridges for future bi-national endeavors, only he and his editors know.

Never does Davidow mention the historical roots of Mexico’s staunchly defended inferiority complex, which is often used to justify inferior behavior: namely, the Arab component of Spanish colonial influence. Mexicans, men particularly, place pride and ego beyond all other considerations, thus sabotaging real honor and the fulfillment of their duties. Like the Arabs who, out of spite as much as politico-religious considerations, blow themselves up throughout the Middle East, Mexicans will gladly sabotage cooperative efforts at solving problems if they are not receiving sufficient recognition or a big enough piece of the pie. Their insurmountable egos create an almost insatiable desire for power and control, one that will see the ship sunk rather than commanded by another. Mexico, writes Davidow, “suffers from an arrested state of national psychological development that too frequently infuses the bi-lateral relationship with adolescent resentment and self-defeating posturing.” If Davidow’s testimony has one shortcoming, it is that he is too diplomatic.

Davidow does give due focus to the unreasonable demands and hypocrisy of Mexican attitudes toward the United States, including repeated mention of their criminality in America. The human-rights issue, which has become almost a cause célèbre for Vicente Fox’s foreign policy, does not help either the average Mexican or American victims of Mexican crimes but only Mexican criminals and lawbreakers in El Norte.

More blood-and-guts facts regarding the negative impact of Mexican crimes in the United States would be instructive. Over 100,000 Mexican felons are currently incarcerated in American prisons, and over 360,000 have already been deported after serving time. Some have returned illegally as members of the prison-formed Barrio Azteca gang (among others) to engage in drug running and other criminal activities. In Arizona alone, Mexicans have committed more than 60 murders, only to flee across the border, where immunity from punishment is virtually guaranteed. Mexican law prohibits extradition if the subject could face the death penalty or life imprisonment, so the villain walks free. A truly objective account of Mexican behavior in the United States would see an astronomical bill sent south of the border for all of the rapes, murders, robberies, carjackings, drug trafficking, and other damage done to innumerable American victims.

Mexicans cry havoc when a Mexican in the United States is facing the death penalty. (Some even accost unsuspecting gringos on Mexican streets to complain about alleged racism up north.) The Mexican constitution, however, provides absurd and biased protections against foreigners, including a prohibition on “agrediendo a un Mexicano” (“insulting a Mexican”), which is punishable by incarceration and deportation. Mexicans commonly hide behind this clause when cheating or abusing foreigners.

Another oversight on Davidow’s part is his faith in Mexico’s lame-duck president, Vicente Fox Quesada,

an honest man . . . a religious man . . . a man who [has] obviously thought carefully about Mexico’s future. He [is] committed to . . . changing the country’s political dynamic to give the people faith in their government. [He has] the ability to see himself at a distance . . . [He is] someone who [can] offer Mexico a concrete plan for the future.

In fact, Fox’s government has abused power and state institutions no less than his predecessors in the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, and Davidow rightly notes that, just as not all that was done by the PRI was bad, so not all that Fox has done is good. Fox has proved himself to be a demagogue, a paper jaguar unable to produce results, irrespective of opposition.

Just what has been achieved with a nonconfrontational Good Neighbor policy of “cooperation,” Davidow’s book never convincingly explains; and any benefit that could possibly be derived by the United States through further integration with such a dysfunctional, failed society remains unclear. Davidow openly admits the failings of current U.S. immigration policy: “[T]aken together, the millions of lies of [Mexican visa applicants] had changed the demographic face of America and made a mockery of US immigration policy.”

And those who did not lie for a visa and risked the mojado border journey played Mexican roulette with their lives: “There [on the border] they suffered depredations at the hands of gangs who robbed, raped, and sometimes killed, often with the connivance of local [Mexican] police.”

Davidow finishes his book with a futuristic prologue leaping forward to 2025, when an Open Borders agreement exists throughout North America, creating an arrangement similar to that of the European Union. But his utopian (or hellish, depending on one’s point of view) theorizing does not address the impoverished, crime-infested, depressed barrios throughout the United States, where Mexicans have achieved numerical majority. More competitive wages would make jobs that attract illegal migrants viable for native-born Americans, thus improving the national economy and greatly reducing unemployment and immigrant crime. Nowhere in his epilogue does Davidow suggest sealing the borders and repatriating illegal migrants; yet these measures might be as good a way as any to prod Mexico toward an understanding of what it means to be, truly, a Good Neighbor.

[The U.S. and Mexico: The Bear and the Porcupine, by Amb. Jeffrey Davidow (Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Weiner Publishers) 254 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply