Way back in prehistory—1991, or thereabouts—a promising Alabaman author started to register on readers’ radars, thanks to lambent reviews from Northern litterateurs surprised to discover that there was at least one Southron who could not only write, but write as though an amphetamined-up James Joyce was simultaneously charioteering Jonathan Swift, Flannery O’Connor, and John Kennedy Toole.

Lee, Tito Perdue’s story of the deeply misanthropic Lee Pefley’s flailing progress through flaccid late-modern America, execrating and excreting as he lashes and limps, displayed “magically evocative descriptive powers, pungent wit and [an] iconoclastic point of view,” marveled Publishers Weekly. Its author, the New York Press opined of a subsequent book, “should certainly be considered among the most important American writers of the early 21st century.” Even the New York Times Book Review noted that there was a “vitriolic and hallucinatory” stranger in town. Educated eyes swiveled South, breaths were inhaled, another Yellowhammer breakthrough (the new Harper Lee?) into the East Coast big time was eagerly expected . . .

And then something happened—or, rather, did not happen. The author kept producing equally dashing novels about Lee at different stages of life, pre-life, and afterlife. These were published by well-known firms and attracted top-drawer admirers, like a certain Thomas Fleming: “Tito Perdue has written some of the best satire on contemporary America, and he has put his criticism in the form of novels which can hold their own with the best postmodern fiction.”

Yet whatever sales there had been slowed, and the briefly proffered palms and plaudits were pulled back—and eventually the author retreated back to his Alabaman ashram, from where he could see but no longer hope to scale the Parnassian heights swarmed over by assorted Updikes, Mailers, Vidals, and lesser imitators. Who knows quite why? Maybe his publishers did not market hard enough. Or maybe rumors started to spread among the kind of people who type reviews for “prestigious” journals that Lee Pefley was not wholly abstract, a monster to be hated/chortled at and then safely locked away between cardboard, but was in fact a distorted reflection of the author, with a license if not quite to kill, then at least to cudgel, raining down reactionary isms on the pates of book-buying innocents. These rumors, which had always been current, could not but have spread, given Lee’s constant worrying at the fallen carcass of the old America, his wicked adherence to difference over sameness and quality over quantity, his rancid rejection of all the old nostrums in favor of infinitely older ones. Manhattan, which had briefly paused, sighed and passed on.

But Perdue kept writing, in a kind of fever, sequestered in the hind part of his ex-nation like a Dark Ages mystic—books incandescent and dangerous as the volcanoes that dot his imaginary Alabaman horizons. And after a time, he made new, less fickle, less easily frightened friends, who felt it reflected extremely badly on American letters that so distinctive and persistent a stylist had been left so long in the wilderness. So he has quietly slipped back into print through small presses, not a late flowering but a careful bringing-out of a sunlight-starved prize specimen from strangling surrounding vegetation. First was The Node (midwifed by Nine-Banded Books); now comes Morning Crafts—and soon Reuben will attempt to strangle snakes in the cradle.

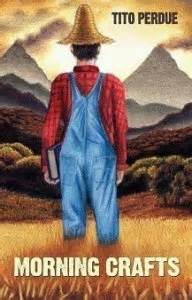

The cover of Morning Crafts, painted by Alex Kurtagic, features a dungareed, plaid-shirted, straw-hatted bumpkin viewed from behind, as he stares (doubtless slack-jawed) at hills beyond which two smoking volcanoes promise both excitement and extreme peril. In his hand is a book—and not just any book, but a proper book, old, large, thick, hardback, probably dusty, almost certainly without any pictures whatsoever. And it is more even than a proper book. It is also a key—the key to the picture, and to Perdue’s passions: the great glories of Western civilization, the wonders of learning and life, the endless igneous possibilities that lie beyond “them thar hills” for a strong-minded minority that takes the trouble to explore.

To begin with, Morning Crafts’ Lee is a slightly reluctant quester for high culture. We meet him first as a 13-year-old, a bucolic cub seemingly content with hoicking harmless bream out of little lakes, and gawping at strangers—like the besuited man who spots something others have not, and asks Lee whether he wouldn’t like to try his piscatorial skills elsewhere, “Where the prey is larger, and the depths so much deeper.” The urchin is inquisitive, and he follows the man, dragging his feet slightly, entangling himself and the man in questions, but ultimately abandoning his prized catch as the man leads him on to new territory. Eventually, they come to a kind of secret and rather Spartan sort of academy, where Lee’s guide and others labor against incredible odds to impart Western Civ., hard science, and antique mores to a small group of young Americans of raw intelligence but less application. And it is more than just education that is imparted at this establishment; as one of the tutors tells him, “advanced instinct is what we seek, refinement without end and the promotion of beauty above everything else.”

At first, Lee resents having been “abducted” (as he sees it); he misses home and nostalgically recalls days of noble savagery far away from Greek verbs or astrophysics. He makes breaks for freedom—but some inner demon always dogs his fugitive feet, drags him back to the academy. It occurs to him as he looks down on the roof of his father’s farm that he has been away too long, seen too much. As Thomas Wolfe could have informed him—had Lee stooped to reading modern novels when there were so many neglected classics unread—you can’t go home again. What Lee has done and discovered has set him fatally apart from his family and old acquaintances—and also from all of America, which so hates all nonfinancial forms of hierarchy, individualism, or quality.

But he finds that he does not mind. Furthermore, he would not have minded even had he known (as we Perduvians know from the other books) that superiority will never bring contentment—although it will bring him at least one great emotion denied to the dwellers on the plain. However high the personal price, it is one Lee has become willing to pay—just as his creator has (presumably) become accustomed to his lack of lionization by the literati.

The book stops, sated with its own weirdness and wit, as the rapscallion turns 14—already unfitted for just about everything the unfit mainstream esteems. He is not yet a man, but he has already become a tragic hero—tragically acclimatized to excellence, to reading by himself in the forest, hearing great sounds, stalking the universe one star at a time, his brain always a-whir, “ruining itself on beauty, aroma, wisdom and the world.” He has just set out on his lifelong progress (which has also been his author’s) toward becoming “naive” in the eyes of an era that knows an awful lot about awful things, but almost nothing else. And even though we know what a terrible, and terribly unhappy, man he is marked out to become, we cannot but wish him well.

[Morning Crafts, by Tito Perdue (New York: Arktos Media) 166 pp., $32.50]

Leave a Reply