As a boy, your author lived in a working-class neighborhood just outside Houston’s city limits. My parents were the children of rural people who had come to Houston looking for work during the Great Depression. They lived in frame houses sitting on cinder blocks in Houston’s West End, a community of people Larry McMurtry called “citybillies,” with chicken coops and deer hanging from trees in small front yards.

We were proud Texans, Southerners, and Americans, and didn’t see any conflict in those overlapping identities. Some of my relations had high, rather grandsounding names—my grandfather was named Oliver Armstrong Allensworth— while others had more common monikers, at least common for their time and place: Billy Lee and Bobby Ray, Flora Mae and Velma.

My relations sinned and suffered but lived mostly happy lives that reflected the culture that made them. Some met tragic ends, but I can’t recall a hint of bitterness in any of them, and none were hateful. They were poor people as measured by today’s standards, but everyone made a living, and some eventually enjoyed a measure of relative prosperity. I’m sure that all of them would have affirmed that America was the greatest country in the world, that God was in His Heaven, and that life could be hard, but joyous as well. They were in no position to indulge in the ideological fantasies of today’s left, or right, for that matter. They were also well aware of two things that the “social justice warriors,” or SJWs, and our Swamp-dwelling Deep State elite have long forgotten: the fallen nature of Man, and the resulting tragedy of existence.

Gentle readers, the point is that our forebears who did so much to define America were far from perfect, but the country they made has been a very good one as far as countries go. I think any fair person would agree to that, not least of all those who are using every method possible to get here, legal or illegal. I’m reminded of a political cartoon I saw recently of a “migrant,” child in tow, turning himself in to the Border Patrol as he wails, “Take me to your concentration camp!”

It’s a country any decent person would forgive a lot of, since there has been far more good than bad in it. What’s more, it’s mine. What yet remains of this great and good land—the American Remnant—is worth fighting for.

It may be hard for some to believe, but no relative or acquaintance of your faithful servant was ever a Ku Klux Klan member. I never saw nor even heard of a lynching. My father did remember hearing of one when he was a boy, but it’s worth noting that during our entire history, lynchings numbered in the thousands—not millions, as the America-haters imagine—and about a fourth of the victims were white, according to historical research by Tuskegee University. They mainly occurred in our distant past, when a frontier mentality was still prevalent. In a more sensible time, ethnic jokes were simply part of the private space, not cause for crucifixion, and your aging chronicler has not heard uttered some of the harsher racial epithets for blacks—at least not by whites—since he was a boy.

Yours truly once worked alongside black and brown people at various manual labor jobs and cannot recall a single instance of strife among the workers. Your correspondent had many relatives who fought the Nazis and never knew any of them to celebrate Hitler’s birthday. We had a number of guns in our house when I was a boy, as did our neighbors, yet I can truthfully claim that no one in my past life was the victim of a shooting. The people we knew could read and write, and my grandfather, who never finished school, was responsible for passing on a love of reading to his grandson. Everyone respected their traditional religion, and some were quite pious. The more hardcore types eschewed drinking and dancing, at least in theory, but none were prudes or Grand Inquisitors in waiting.

In short, the people I knew and know were not and are not the pack of yahoos, peckerwoods, yokels, or not-so-closeted fascists portrayed in Tony Horwitz’s final book, Spying on the South, which reads like a bloated Salon magazine article. I’ve known some folks one could classify as “white trash,” but they were not the norm, and were not as prone to violent crime as some of the so-called underprivileged groups our SJWs treat as sacred objects bereft of agency and free will.

Spying on the South is ostensibly a recreation of Frederick Law Olmsted’s journeys across the South before the Civil War, which he duly recorded for posterity. The abolitionist journalist and landscape architect of New York’s Central Park and other landmarks, traced a route from West Virginia to Texas. The author of the volume in question, Tony Horwitz, retraces that route, comparing his impressions to those of Olmsted. That’s the pretext for Horwitz’s writing this lazy, shallow, unsympathetic portrait of the people and places he encountered along the way.

To his limited credit, Horwitz did wonder whether his “spying” on the people he admitted had treated him with hospitality, friendliness, and courtesy was devious. But he gave us a glimpse into his exploitative mentality when he also admitted the thing he liked the best about the South—the friendliness of the people—enabled him to get to know them before trashing them in this book.

Before he died in May, Horwitz was midway through a storied career of writing books that targeted the South. His most well-known work, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize, was Confederates in the Attic (1998). Indeed, Horwitz was a leading light of the anti-Southern genre currently in vogue, which includes books such as Lawrence Wright’s God Save Texas, and other books intended for the same people who misread J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy for the purpose of laughing at the hicks. Horwitz’s writing presented a picture of Southern life and culture that reflected his view of the region as a black-comedy Hee Haw, in which the coal-barge workers, monster truckers, Cajuns, fundamentalist “Young Earth” Christians, and Trump “MAGA” supporters he encountered were caricatures reminiscent of the hillbillies in Deliverance, with an occasional Boss Hogg thrown in to represent backwater sophistication. Horwitz reported that the people he encountered in his supposedly nonfiction book conversed in racial epithets as a matter of course. But I have my doubts. It’s possible that Horwitz, following the example of the “fake news” media, did some creative editing of their remarks, or simply made up portions to paint a picture confirming “The Narrative.” Namely, that slavery once existed in the South (Gasp!). The people there often own guns and are frequently serious Christians (which is a big problem for Horwitz, who often expressed his disdain for religious faith). They voted for Trump, which makes them inclined to fascism. What’s more, the foul-mouthed characters Horwitz loved to quote are irredeemably white and actually display American patriotism!

Spying on the South often reads like a litany of incest jokes, wisecracks about Southern food (“fried chicken, fried gizzards…It’s a worry when McDonald’s is your healthy meal of the day.”), commentary on the habits of meth heads (“[g]aunt and jumpy, Marty read like a pamphlet titled Warning Signs of Crystal Meth Use…”), sneering references to pistol-packin’ Southerners (“‘You’ll never catch me out of my house without my .9 or my .45,’ says one Louisiana man,” which shocks Horwitz and his traveling companion), and snark about Southern valor (Horwitz has no use for Crockett and Travis, and does his level best to diminish the historical significance of the Alamo and the Battle of San Jacinto, which, he disparagingly notes, only lasted 18 minutes). Helping Horwitz along his cliché-ridden journey is his travelling companion, Andrew, an Australian euthanasia advocate who says of friendly Texans, “They’ll love you right up until they kill you.”

The theme of Spying on the South is that “nothing has really changed” (as one of Horwitz’s interlocutors puts it) across that “great divide” separating the South from Horwitz’s Real World, apparently represented by Manhattan, Washington, Berkeley, and Portland. The South, as cast by Horwitz, is mired in a social system that remains essentially antebellum in nature. He provides a distorted picture that lacks historical perspective, and which relies on a post-modern approach to truth, in order to achieve his political aims. Thus, slavery in the Old South is compared to (what else?) the Holocaust, and slaveholders to Stalin—which raises the question of how the black population in America was able to increase exponentially under a supposedly genocidal system, and yet Jews and kulaks perished by the millions under Herr Wolf and the Man of Steel.

Roger McGrath, writing in the June Chronicles, noted, for instance, that only a small minority of the slaves imported to the Americas went to the British North American colonies, “yet the largest population of blacks in the Western hemisphere today is in the United States.” Dr. McGrath also pointed out that conditions for white workers at the time were often harsher than those for blacks, and that free blacks owned slaves, which is something Horwitz at least mentions, without pointing out the scale of black slave ownership (according to Dr. McGrath, over 20,000 black slaves were held by 4,000 freed blacks). Horwitz also fails to mention that blacks shipped to the Americas were sold by other black Africans, and that slavery was a historically universal institution that still exists in some parts of the world today, including on the African continent.

Spying on the South actually tells us a lot more about Tony Horwitz and his readers than about the South. The SJWs’ historical ignorance, lack of self-awareness, and anti-Americanism has fueled the mass hysteria known as “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” a phenomenon evident in Spying on the South. Thus, Horwitz’s Narrative demonstrates the left’s tendency to portray the “deplorables” backing Trump as extremist Klansmen and neo-Nazis on a violent rampage, rather than the hospitable, friendly, and courteous folk he admits to encountering on his journeys.

Further examples of the mirror-world of The Narrative: Trump is supposedly a fascist who plans to suppress free speech, while Silicon Valley totalitarians censor conservatives from the Internet in the name of combating “hate.” Alleged foreign interference is undermining our democracy, while the globalist activists attempt to dissolve the nation itself, and Democrats ponder abolishing the electoral college and packing the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, suicide is on the rise in the American heartland, and deaths of despair driven by opiate addiction are diminishing the core of the nation. That’s a story Horwitz doesn’t deign to mention.

For Horwitz and the choir he preached to, America is uniquely evil, alone in bearing the stain of Original Sin they deny in themselves. What right have they, the supporters of abortion on demand, outright infanticide, and euthanasia, to judge the past? How can the preening left that celebrates transsexual delusions and promotes such cultural vomit to children assume moral superiority over Middle America? Slinking cowards like Horwitz and his pal Andrew could only dream of emulating the courage and sense of honor of a Jackson, Crockett, or Lee.

A simple mental exercise might be worth pondering: Let’s suppose that during Tony Horwitz’s journey his car broke down and he could have chosen where that event would occur: an urban slum, or a Southern rural community. Does anyone believe that he would have chosen a ghetto over a Southern rural community?

Horwitz disingenuously states in Spying on the South that he had hopes of promoting a “dialogue” with the inhabitants of a section of the country he insinuates are beyond redemption. But his version of dialogue turns out to be a preachy, one-sided propaganda tirade. It’s not unlike the prissy, presumptuous lectures we’re used to hearing from the leftist intelligentsia, which are applauded by their audience of screeching harpies and effete snobs, circus freaks and weirdos bent on exacting revenge upon the world.

Horwitz’s writing is seemingly driven by a resentment against the institutions that support civilized life, especially the family and the Church, and a perverse desire to “revaluate” all traditional values. Thus, the grotesque is celebrated over the beautiful, disloyalty over patriotism, and all normal attachments are mocked and undermined. Ingratitude is a hallmark of the SJWs, and Tony Horwitz’s obvious disdain for America is particularly ungracious coming from someone who had done very well in a country that he nonetheless resents.

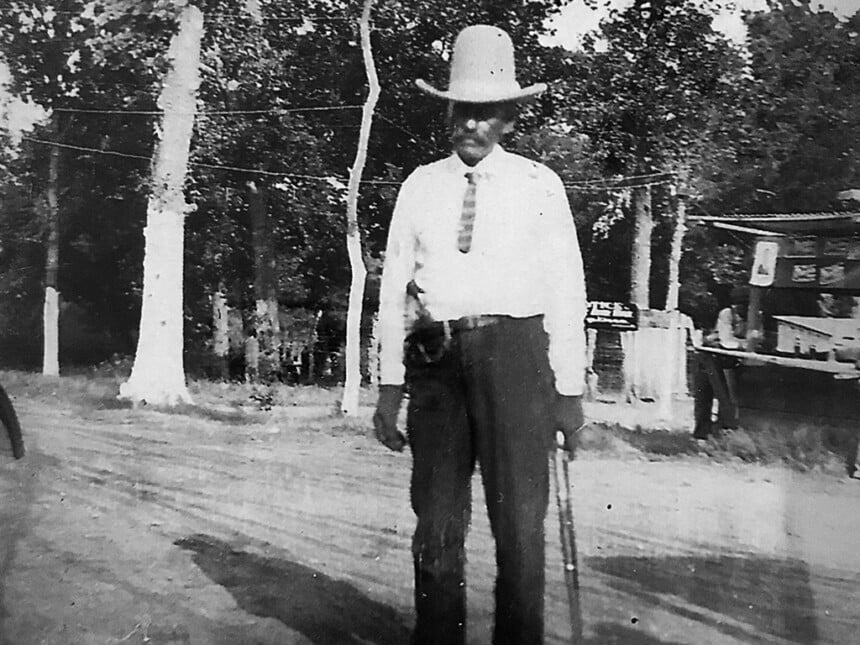

I often survey the rows of photographs, images of a lost world, hanging on the walls of my parents’ house: A lean man with a handlebar moustache, my great grandfather, wearing a white Stetson and holding a repeating rifle, the sheriff’s badge pinned to his shirt. A farmer with a determined look, a great-great grandfather, holding a shotgun, his wife beside him, a forlorn windmill in the background. My grandfather in a black Stetson, cigarette dangling from his lips, standing with his brothers outside a tiny, lonely house somewhere on the prairie. My great-grandfather Sam in a flannel shirt and suspenders skinning a deer in Aunt Peggy’s yard. My teenaged father posing outside Taft’s beer joint, “The Swanky Inn,” in Galveston. My brothers and I at Christmas in the old house, the one my father built in 1955…

Spying on the South is an attack on how we in the American Remnant think about our ancestors and our heritage. It’s a hit piece on “legacy America” that uses the left’s favorite target, the South, as a stand-in for Middle America as a whole. The South plays its role in the SJW Narrative as the favored initial target in the program to extinguish the old America once and for all, a country they see as illegitimate and evil from its very beginning. It’s up to us, dear readers, to defend the history of what has been a great and good country—our country.

[Spying on the South: An Odyssey Across the American Divide by Tony Horwitz; New York: Penguin Press; 496 pp., $30.00]

Image Credit: Wayne Allensworth’s great-grandfather James Franklin Allensworth in Caddo County, Oklahoma, at the turn of the 20th century

Leave a Reply