“Therefore nowe is it tyme to me

To make endyng of mannes folie.”

—The Last Judgement, York Cycle Plays

Nothing seems very certain nowadays for writers of fiction. Traditional religious and moral values have been under attack for so long that many writers uncritically assume they are thoroughly discredited. Even much of the certainty of science is now considered tentative, history is equated with fiction, and the very notion that language can represent reality is frequently denied. But writing, like other human activities, is generated out of a sense of purpose, and purpose presupposes certainty of some kind. For many contemporary authors the one remaining certainty standing as foundation for purpose is the force of narrative.

The enduring attraction of narrative seems coextensive with human existence itself. In a world of relative or indeterminate truths, this certainty can be relied upon: humans love stories. Thus narrative, as an end in itself, has become for many writers the ultimate concern. And if Paul Tillich was right about faith being ultimate con cern, narrative has become their faith, their religion. Some devote themselves to the mysteries of narrative technique with the fervor and reverence of a theologian devoted to the mysteries of heaven. These two Latin American novels provide contrasting examples of this current preoccupation with the force or appeal of narrative, the one demonstrating fertile abundance in variety of character and incident within the limits of realism, the other demonstrating a similar fertility in self-conscious anti-realism.

The War of the End of the World is a fictional treatment of an actual event in Brazilian history, the remarkable heroic resistance of the backland natives at the siege of Canudos in 1896-97.The energizing force behind this resistance was a charismatic religious fanatic named Antonio Mendes Maciel, known as Antonio Conselheiro (the Counselor), who gathered about him the poor and alienated inhabitants of one of the most inhospitable back land regions of the country. With his preaching against the new Brazilian republic and his apocalyptic vision of the destruction of the forces of the Anti-Christ, he welded the dispossessed into a guerrilla army that repeatedly humiliated government forces until the full resources of federal troops eventually succeeded in destroying this strange leader and his remote stronghold.

Vargas Llosa, a Peruvean, used as his principal source Os Sertoes by Euclides da Cunha (Rebellion in the Back/ands is the title of the English translation). This 1901 Brazilian classic has been called “the Bible of Brazilian nationality.” It is a perfect do-it yourself kit for a novelist because in addition to narrating the events of the battles it has long and detailed chapters describing climate, geography, flora and fauna, and the racial, social, and cultural characteristics of the people, including a biography of Antonio Conselheiro, described by da Cunha as a man existing “indefinitely on the wavering frontier of madness, in that mental zone where criminals and he roes, brilliant reformers and moral defectives, meet and genius jostles degeneracy.”

Another source available to Vargas Llosa but unsuited to his purposes is R.B. Cunninghame-Graham’s A Brazilian Mystic, Being the Life and Miracles of Antonio Conselheiro. This book does not add much to da Cunha’s, and as a matter of fact, Vargas Llosa makes no attempt to explore the life and personality of Conselheiro. One would expect a novelist to seize upon this unusual and complex personality, but in this novel the Counselor plays only a minor role. The focus is on the people he inspires and the events generated by their attachment to him.

The War of the End of the World is large and panoramic, displaying extraordinary imaginative inventiveness, the kind of fertile inventiveness demonstrated in the author’s last novel, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, but pushed to an even more ambitious level. In alternating sections our attention is drawn to dozens of characters ranging from a wealthy and worldlywise baron to a bearded lady in a pathetic traveling circus composed of a handful of grotesques. As the battles progress, we shift back and forth to simultaneous scenes involving various combatants on both sides as well as those caught in the middle, and we move forward and backward in time for multiple perspectives on the principal events. The dust-jacket comparisons with the great historical novels of Tolstoy and Stendhal should not be taken lightly. This is obviously a stunning and significant novel.

The comparisons with large-scope historical novels of the past century, however, need qualification, and this brings me back to my initial point about contemporary preoccupation with pure narrative. Vargas Llosa has said he does not like novels with morals, and this novel certainly propounds no overt morals. Indeed it differs from those large 19th-century novels by appearing indifferent to major themes, ideas, or conclusions. The phenomenon of Antonio Conselheiro and his rebellion in the backlands poses a multitude of baffling questions. Vargas Llosa makes no attempt to answer them. His refusal as narrator to get inside the minds of the Counselor is perhaps symptomatic of his interests and approach. His objective is to provide rich, engaging, often startling narrative as an end in itself. Of course every narrative will bear to some degree the stamp of the author’s character and philosophy, and one such as this that describes so many characters and incidents is bound to touch upon a variety of themes and issues. Nevertheless, the dominant motivation behind The War of the End of the World is story for story’s sake. I’m certain that Vargas Llosa would concur with Richard Poirer’s notion that “literature has only one responsibility—to be compelled and compelling about its own inventions.”

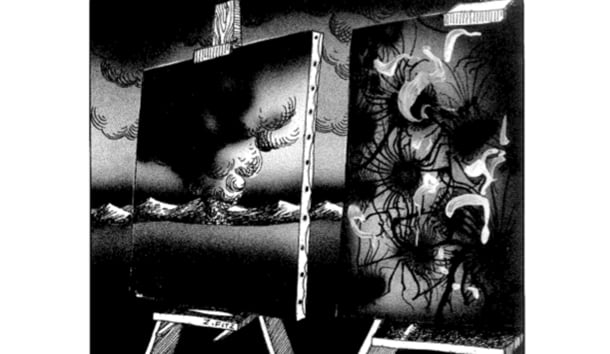

José Donoso’s A House in the Country is another impressive feat of the imagination, but a more problematic one. It is set in the backlands also, this time in an unidentified South American country. Donoso himself is a Chilean. In the novel, a wealthy family composed of seven sets of parents and 35 cousins spends its summers in a large country estate in a remote region. The house is enclosed by an iron-lace fence, which forms a barrier against a vast and encroaching prairie of thistles and against the natives—thought to be cannibals—whom the family exploits to mine gold and hammer it into fine sheets for export. Here the adults live in selfish luxury and self-deception while the children pursue their own elaborate games of incestuous intimacies, jealousies, and intrigues. When the adults leave for a picnic that lasts a day for them but a year for the children, the children’s “games” are transformed into a nightmare of anarchy and destruction. The fence is torn down and children, servants, and natives engage in a bloody struggle for power.

The novel is self-consciously antirealistic. The narrator intrudes periodically to remind us that everything is his own rather arbitrary invention. “By intruding myself from time to time in the story I simply wish to remind the reader of his distance from the material of this novel, which I would like to claim as something entirely my own, for exhibit or display, never offered for the reader to confuse with his own experience.” The strategy is precisely that described by Gerald Graff in a chapter of Literature Against Itself tided “The Politics of Anti-Realism.” Graff explains that the enemy of mimesis believes that by acknowledging the representational nature of literature we reconcile ourselves to the established order. On the other hand, by refusing to imitate nature, by rejecting the very idea of a stable “nature,” literature strikes at the psychological and epistemological bases of the ruling order, which is the product of bourgeois myths.

Donoso’s narrator explicitly rejects “the mimetic concept of art.” Realism is unpalatable to him “because every attempt at ‘realism’ however unpleasant or disturbing, always meets with official approval, since in the final analysis it is useful, instructive, it points out, it condemns.” He chooses the alternative of an “exaggerated artificiality” as a means of creating “an equally portentious universe: one that might similarly reach and touch and call notice to things, though from an opposite and disapproved angle, since artifice is a sin for being useless and immoral, whereas the essence of realism is its morality.”

Much can be said for this strategy. It bears resemblance to that of Hawthorne, who walked the narrow frontier between the real and fanciful in order to treat more profoundly the truths of the human heart. But the differences are significant. Donoso doesn’t walk that frontier; he obliterates it and thumbs his nose or makes obscene gestures at those on the side of realism. Thus, what Hawthorne gained is lost to Donoso.

A primary weakness in the strategy is an over-reliance on the power of pure narrative. Donoso’s narrator insists that there is nothing in his pages, as complicated as they might at times appear, “that can’t be grasped as pure narrative.” In fact, he suggests that “pure narrative is the true protagonist in a novel that sets out to grind up characters, time, space, psychology, and sociology in one great tide of language.” His confidence in the forceful attraction of pure narrative is that of a true believer. No amount of artificiality or implausibility can negate that force. At the end of the book he makes a special point of saying that “in spite of having created my characters as a-psychological, unlifelike, artificial, I haven’t managed to avoid becoming passionately involved with them and with their surrounding world.” And he intimates his assumption that his readers have experienced the same passionate involvement.

I was not passionately involved. Instead, I felt impatient with Donoso’s self-indulgent trifling with artifice as a means of making thinly disguised angry and hyperbolic commentary on his government and society. It seems a form of cheating to deny responsibility for representing reality or that reality can be represented at all, while leveling charges of the most grievous cruelty and barbarism. The lure of pure narrative lies behind this cheating. The contemporary writer, defensively recoiling from the oppression, exploitation, and violence in modern life, seeks to escape complicity by repudiating rationality and representation and perhaps even meaning itself. But men and women being what they are, “pure” narrative remains ultimately an illusion, and its pursuit serves only to widen the division between art and society and gives impetus to the spiral of artistic impotence and alienation.

Maybe the ineluctable and enduring appeal of narrative is a reasonable article of faith, but only if we understand that that appeal is conditioned and not absolute. Narrative’s power over us diminishes with exaggerated implausibility. Artifice or fantasy played off against the real can delight and illuminate, but used programmatically to undermine confidence in the real may only confuse and unsettle. Vargas Llosa’s novel demonstrates the power and charm of narrative, even pursued primarily as an end in itself, when it remains within mimetic bounds, Donoso’s novel demonstrates the emptiness and confusion that result from an aggressive and politically centered anti-realism.

[The War of the End of the World, by Mario Vargas Llosa; Farrar Straus Giroux: New York]

[A House in the Country, by José Donoso; Alfred A. Knopf; New York]

Leave a Reply