Some years ago, in a discussion with the late Joe Sobran about the motivations of those managing our vastly overstretched empire, I pointed out that, for certain strata of the bureaucracy (the people who meet with E.U. officials in Brussels and attend cocktail parties in Georgetown, for example), as well as think-tank warriors theorizing about battles they will never fight themselves, empire can be great fun. For our ruling class, detached as it has become from the country whose interests it pretends to defend, managing a vast empire is loaded with opportunities for travel, career advancement, and a sense of superiority to a rabble concerned with mundane problems like crime, schools, employment, or filling potholes. And yours truly should not have left out the lower echelons of the vast machinery of empire—the foot soldiers of the bureaucracy, who can play at being Lawrence of Arabia or James Bond, whichever suits their fancy, never questioning what the endgame is or why the game is being played at all. The game is an end in itself, providing escape for the seasoned player from those common, everyday chores (family, church, community) that fail to stimulate the interest of rootless and detached people whose personalities have been shaped by a smarmy and nihilistic culture of cheap irony and smug sarcasm.

But there is something else driving imperial expansion, something veteran Foreign Service Officer Peter Van Buren clearly reveals in his readable, tragicomic account of one year in Iraq working at a Forward Operating Base as part of a Provincial Reconstruction Team. He was among soldiers, spooks, and careerist bureaucrats, many of them content to spend their tour of duty ensconced in the World’s Biggest Embassy—air conditioning purring away, water flowing (to irrigate the embassy lawn, planted in a desert) as freely as the booze in the embassy bar, in a land devastated by war and lacking clean water, sewage treatment, and jobs. When a former colleague commented (after his own small adventure in the empire’s outback) that Washington was carrying on multiple wars to see to it that Afghan (and Iraqi, and Libyan) women could have abortions and get driver’s licenses, he was not far off the mark. For no matter how careerist and cynical a particular official cog in the bureaucratic machinery might be, that cog has been molded in the forge of evangelical liberal-democratic imperialism. It’s what Jacobinism and Bolshevism look like when stamped with the puerile smiley face of Western democratic ideology.

It is important to keep Washington’s soft totalitarian assumptions in mind while reading Van Buren’s catalog of wasteful, utterly useless “reconstruction projects,” designed on the ideological level to transform Iraq into a consumerist democracy, and on the practical level to serve the immediate purposes of bureaucrats (showing “progress” in reports to higher-ups). At times it reads like satire. As they say, you can’t make this stuff up.

“Empowering women,” especially by employing them outside the home, and otherwise pushing liberalism’s ideological agenda, was always a priority in the various “reconstruction” and “hearts and minds” projects. Van Buren wryly observes that “The plan was that disadvantaged Iraqi women would open cafes on bombed out streets without water and electricity.” Another plan gave $22,500 to the Iraqi Artists Syndicate for the production of a play (Under the Donkey’s Shade) preaching against sectarian violence. Money was spent on publishing children’s calendars stressing “peace . . . education, tolerance” in order to “advance civil society.” American dollars bought bicycles for children to use “on streets filled with trash, pockmarked with shell craters, and ruled by packs of wild dogs.” A number of projects were targeted at farmers (if earmarked for women farmers—not exactly a large segment of Iraqi society—so much the better), including the investment of money in seed for wheat to be grown in the desert. (“The locals, knowing the crop would fail for lack of water, sold the good seed for a profit, bought some cheap stuff, and watched the sprouts die in the field.”)

And those were the small projects. Others, equally crazy, easily cost tens of millions of dollars, including an ineffectual English-language academy for Iraqi bureaucrats ($13-$26 million); a “road to nowhere,” intended to increase commerce, which had to be closed after it proved to be a convenient route for insurgents (“Cost: unknown”); and a roofless hospital built by the Army and abandoned for security reasons (“Cost: no one will ever know, but in the millions”). The list goes on: almost $9 billion unaccounted for in an audit of Army reconstruction projects; a $40 million prison that was never used; a $171 million hospital “opened” by Laura Bush in 2004 that has never seen a patient; and numerous other projects whose cost Van Buren calculates at a total of $5 billion. These projects accomplished little or nothing, except to serve the interests of corrupt Iraqi officials, shrewd and greedy sheiks and tribal leaders eager to enrich themselves from the (literal) piles of readily available American cash, and American civilian and military officials aiming to “punch their tickets” on the way up the career ladder by holding a Baghdad Flower Show, sewing classes to promote the “freedom-liberation-empowerment” of Iraqi women, or “some [other] kind of g-damn chick event” to satisfy the feminist “line of effort.”

Van Buren’s account confirms that the Bush administration went to war with no postwar plans, but on the insane assumption that Iraqis wanted to be like “us.” To his credit, Van Buren recognized that they did not; that establishing chicken farms and milk-processing plants (both of which failed at great cost, largely from ignorance of basic economics as well as of local conditions) would not dissuade Iraqis from joining the insurgency; and that Islam and the violence Americans had perpetrated in invading their country and killing their friends, fellow tribesman, and relatives had something to do with the subsequent violence in Iraq. As Van Buren notes, a major task in the reconstruction effort was to

convince yourself of the overall premise of the US efforts, that Iraqis want to be like us. They want to have . . . fast food, rock and roll, MTV like us. Hire Iraqis who see it our way, find young women who change from hijabs into club wear on campus, happy natives to confirm our visions . . . Enjoy the Kool-Aid, sweet even when it is bitter.

And the Iraqi women who received so much attention from reconstruction officialdom?

The area women were clear that they liked their veils and they liked raising their kids, and they worked hard to make sure their daughters grew up the same way. Few of our efforts acknowledged this, and many times we proceeded into failure believing the Iraqis wanted to be like us, sustained in our vision by locals who had learned that goodies would flow if they said the things we wanted to hear.

All of these projects and “goals” were couched in the arcane gibberish of acronym-heavy bureaucratese, the nonsensical “line of effort” serving the Big Lie that “reconstruction” in Iraq was successful. Van Buren offers this sample of the use to which QRF (Quick Response Funds) cash was put:

QRF proposals must be tied to the recently updated PRT work plans, per OPA and QRF policy. Proposal themes in the database are based off the old PRT Maturity Models and will continue to be used as broad indicators of targeted impact. The QRF team will coordinate with the OPA Plans Office to ensure proposals fall in line with PRT strategic objectives.

To be plain, the masters of the universe simply don’t know what they are doing. Despite their pretensions to intelligence and education, they tend to be hopelessly ignorant of the world outside the Beltway bubble; filled with hubris; arrogant, shallow, and irredeemably provincial—even naive—in their childlike, vulgar manner and in their unshakable belief not only that Iraqis, Afghans, and Libyans want to be like “us,” but that the American Empire can achieve the dystopian goal of converting vastly alien peoples into soulless and banal yuppies.

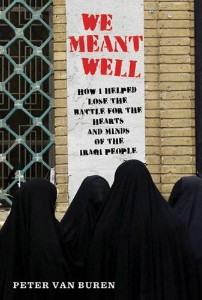

[We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People, by Peter Van Buren (New York: Metropolitan Books) 269 pp., $25.00]

Leave a Reply