The pro-life movement today almost completely identifies with the Republican Party, despite its support by a few Democrats such as Pennsylvania Sen. Robert Casey (sometimes). It wasn’t always so.

In 1972, at the age of 17, I worked against Michigan’s Measure B, which would have legalized abortion in the state. It lost, with 61 percent of Michiganders opposed. Most of the pro-lifers in Detroit and the industrial suburbs to its west were Democrats, including state Rep. Tom Brown, a friend of my father’s. Those Democrats included what then were called “ethnics,” especially Poles, Italians, and Irish; whites from the South; and, overwhelmingly, black Democrats in Detroit.

The pro-aborts who were backing Measure B largely were wealthy Republicans, including then-Gov. William Milliken and his wife, Helen.

All that began to change the following year with Roe v. Wade, which overturned not only state laws outlawing abortion but also state laws that legalized but regulated abortion, such as those in New York and California. Since Roe, more than 57 million babies have been slaughtered.

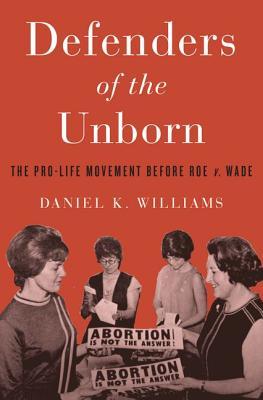

Daniel Williams’s book is the first comprehensive review of the pro-life movement in the pre-Roe years. Williams notes that, although Catholics played a major role among pro-lifers, and

The media portrayed the pro-life movement as a Catholic cause . . . by 1972, that stereotype was already outdated. In Michigan, for instance, the fight against a referendum to legalize abortion was spearheaded by three Protestants—a gynecologist, a white Presbyterian mother and an African American woman who was a liberal Democratic state legislator.

In New York, where abortion had been legalized in 1970 under Republican Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, “Catholics had joined forces with Orthodox Jews” to fight for the unborn.

Standard histories of the legalization of abortion

do not mention the African Americans in Detroit, the Lutheran wheat farmers in rural North Dakota, or the Catholics in Midwestern parishes who mobilized on behalf of the unborn at the beginning of the 1970s.

It was a remarkable grass-roots movement, a truly democratic reflection of the will of the American people. That will was mocked openly by Roe’s cruel distortion of the Constitution.

But Williams goes back even further, detailing how pro-life activism “actually began decades before Roe v. Wade. . . . And it originated not as a conservative backlash against individual rights,” the putative argument behind Roe, “but as a defense of human rights for the unborn.” The movement actually was closely aligned with liberal human-rights movements, such as those to advance the rights of blacks. In the pre-Roe period, pro-life arguments

drew on the same language of human rights, civil rights, and the value of human life that inspired the struggle for African American freedom, the feminist movement, antiwar protests and the campaign for the rights of gays and lesbians.

Of course, the situation quickly became contradictory. A majority of blacks, for example, have always been pro-life. Yet they continue to vote overwhelmingly for candidates of the explicitly pro-abortion Democratic Party.

Purchase your copy of Defenders of the Unborn here

Following World War II, as the West learned of horrors committed by the Nazis, pro-life Americans also drew comparisons between the holocaust and the abortion genocide—comparisons that are still made today. In 1951, Pope Pius XII declared that “every human being, even a child in the mother’s womb, has a right to life directly from God.” He attacked those who believed it was licit to destroy that which is deemed “life without value,” a phrase stemming from euthanasia laws of the pre-Nazi Weimar Republic and adopted and expanded by the Nazis. And the pope compared those committing abortions with Nazis killing people with “some mental or physical defect.”

“Within the next fifteen years,” Williams writes,

the comparison between abortion and Nazi eugenics or the Holocaust would become so common in the Catholic press that it would be hard to find a right-to-life advocate who did not make it. . . . Catholics who had been speaking out against birth control and eugenics for several years before the rise of Adolf Hitler did not need to see reports of the horrors of Auschwitz and Buchenwald to believe the worst about the likely consequences of legalized abortion. But the hideous results of Nazi eugenics gave them new reasons to believe that if their fellow citizens ever removed the law’s protection of an entire class of humans simply because those people had not yet been born, those consequences would be ghastly.

As is the case today, in 1950-65, advocates of legalized abortion resented these comparisons, framing their cause as one of human liberation. Yet mainstream opinion in America, including that of the media, reflected a strong belief that, as Vatican II put it, “abortion and infanticide are unspeakable crimes.” This view is reflected in the popular culture of the period. In the 1951 film noir Detective Story, for example, Kirk Douglas pursues an abortionist whose unspeakable actions aren’t directly mentioned, although moviegoers understood the nature of his villainy.

Williams recounts the long legal battle over abortion. The country still had some degree of federalism, so the battle was fought at the state level. In 1959 the American Law Institute “endorsed abortion liberalization by making it part of ALI’s model penal code.” ALI lawyers argued that, as hospitals across the country already were performing thousands of abortions, statutes ought to be made consonant with practice.

Purchase your copy of Defenders of the Unborn here

Catholic lawyers responded by “translating their arguments for fetal life into the language of constitutional law,” which “created a nonsectarian defense of fetal rights that could reach a much broader audience than natural-law based arguments ever could.” Such arguments have been repeated in dissents written by Clarence Thomas and the late Antonin Scalia.

A key time was 1962-63, when Catholic political power in the United States was at its peak, strong enough to excommunicate segregationists in the South. Whereas today, Catholics such as Vice President Joseph Biden and Govs. Jerry Brown and Andrew Cuomo defiantly support the right to abortion, Catholic politicians of that time never dreamed of relaxing restrictions on the practice.

Back then, legislators in several states introduced abortion liberalization laws based on ALI’s agenda. Pro-life advocates defeated this agenda first in Minnesota. The major battle, however, was in California, where a young lawyer, Walter Trinkaus, representing the Catholic Conference of California Hospitals, testified before the state legislature. In Williams’s summary, Trinkaus argued that every unborn child had “a constitutional right to life under the Fourteenth Amendment that no state law could take away.” Trinkaus and others defeated liberalization laws for the time being. But their victories made Catholic pro-lifers overconfident, Williams says.

In 1964, abortion zealot Alan Guttmacher and other physicians and lawyers formed the Committee for a Humane Abortion Law. For several years before Planned Parenthood endorsed legalized abortion in 1968, its officials were already doing so; the committee’s honorary cochairs for fundraising were former presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Harry Truman.

In 1965, California state assemblyman Anthony C. Beilinson (later a state senator and U.S. representative) began pushing a new therapeutic abortion bill. “More than 1,100 Protestant and Jewish clergymen had signed a petition in support of Beilinson’s bill, as had more than 1,000 doctors,” Williams writes. But for one last time, the pro-life forces prevailed—barely.

Then the dams broke. In 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Griswold v. Connecticut decision struck down state prohibitions on birth control under Justice William O. Douglas’s infamous claim to have discovered “penumbras, formed by emanations” in the Bill of Rights. This was another judicial fraud of the Warren Court. In practice, Connecticut’s antiabortion laws were largely flouted, and liberal New York City was close by. The federal government, wanting justification to fund population-reduction measures at home and abroad, rapidly sank the national birthrate below replacement levels. Eight years later, Roe cited Griswold in legalizing abortion.

Purchase your copy of Defenders of the Unborn here

“At the same time,” writes Williams, “the reforms of Vatican II brought a tsunami of cultural change within the Catholic Church. Laypeople quickly began defying clerical authority, especially on the issues of birth control and abortion.” Pope Paul VI’s Humanae vitae in 1968, and numerous later documents by Pope John Paul II, upheld the old strictures, and as recently as a couple of years ago a few politicians were denied communion by American bishops. But without excommunications, Catholic doctrine had no teeth, and politicians took the pro-abortion positions paid for by their wealthy contributors.

In 1967, Colorado became the first to legalize abortion at the state level. Then California enacted a new Beilinson bill, supported by several conservative Republicans. After obtaining minor changes to the legislation, Gov. Ronald Reagan, newly in office, signed it into law. Williams writes, “The Right to Life League emerged from the fight angry, disappointed, and internally divided”—a situation that has hampered the movement ever since, even as the pro-abortion movement has largely been united, and the abortion industry grabs billions of dollars every year for tax-subsidized abortions. Reagan later regretted his action. Yet as President, he also appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, despite warnings from Howard Phillips and others, pro-abort Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy. The latter continues to plague the country, most recently in the Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, which struck down almost all restrictions, even legal provisions designed to protect women’s health, on abortuaries. Of the five-member majority in that decision, Kennedy and Sandra Sotomayor identify themselves as Catholics.

What followed in other states after 1967, including the Michigan of my youth, was guerrilla warfare over abortion. Pro-lifers debated the propriety of displaying graphic images of abortion, and many of them did so. Even as the Mainline denominations backed liberalized abortion laws, evangelicals embraced the pro-life cause. Women such as the remarkable Phyllis Schlafly became pro-life leaders. Fr. Paul Marx started the Human Life Center, later called Human Life International. African-Americans played an increasing role in the movement.

Defenders of the Unborn is a vital history of the noble efforts of the previous era to protect the unborn.

[Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade, by Daniel K. Williams (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 400 pp., $29.99]

[Slideshow Image: By jordanuhl7 [CC BY 2.0]]

Leave a Reply