“Friendship is like two clocks keeping time.”

—Anonymous

Walker Percy was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 7, 1916, the eldest son of a prosperous lawyer and a Georgia socialite. In addition to patrician lineage, Percy enjoyed a birthright of wealth and privilege. With these amenities, however, came a familial predisposition to depression and suicide. After their father’s suicide in 1929 (and that of their paternal grandfather), Percy and his brothers moved with their mother to their Grandmother Phinizy’s house in Athens, Georgia. The following year their bachelor cousin, William Alexander Percy, invited the displaced family to come to Greenville, Mississippi, where he felt the boys would receive greater cultural advantages. Delighted with the stimulating life at Uncle Will’s house, where writers and intellectuals came to visit routinely, the boys prospered until the bizarre death of their mother who, with her youngest son Phin in the car, drove off a bridge and drowned. Although her death was never determined definitely to have been a suicide, Phin suffered for years recalling that his mother had not only refused to swim out of the car but tried to keep him from escaping as well. Although he seldom talked about his father and mother, Walker Percy’s grief and perplexity at their deaths continued to haunt him throughout his life.

Never completely alone or without resources, however, 15-year-old Walker, 14-year-old LeRoy, and ten-year-old Phin were adopted by Will Percy: planter, lawyer, poet, and author of Lanterns on the levee. The Percy boys’ devotion and gratitude to their uncle and his dramatic influence on their lives cannot be overstated. Even Shelby Foote, the young friend whom Will Percy recruited to help make his cousins feel welcome in Greenville, found himself similarly enthralled by the possibilities that life at Mr. Will’s house offered.

When Walker showed aptitude in science. Will Percy encouraged him to study medicine. Thus, following graduation from Greenville High School, Percy spent four years at Chapel Hill and then entered Columbia Medical School, where he specialized in pathology. When not in class or studying, Percy went to the movies and read, pastimes he pursued in earnest throughout his life. He also underwent psychoanalysis, an experience of apparently negligible value despite the frequency of the sessions and the duration of the treatment. After graduation, Percy returned to New York to intern at Bellevue Hospital, but his training was interrupted when he contracted tuberculosis. Forced to withdraw and seek rest cure, Percy spent the next two years in a TB sanatorium at Saranac Lake, New York, where he had little to do but read and think. Putting aside his medical books, Percy turned to philosophy and literature; according to Shelby Foote (who visited him there), “Walker was holding on to those books for dear life.” While his greatest influence from this time was Kierkegaard, Percy also read Heidegger, Marcel, Sartre, Camus, Mann, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky, among others. Kierkegaard’s statement that Hegel “explained everything under the sun, except one small detail: what it means to be a man living in the world who must die” was crucial to Percy’s emerging shift in thought, since it pinpointed the single shortcoming of science and medicine that made all the difference. After leaving “The San,” Percy spent another four months in a Connecticut sanatorium before being released for good.

Dislodged from his old life and at loose ends with regard to a new one, Percy stopped briefly in Greenville before heading west in search of a good climate and the answers to questions over which he had long been brooding. At a dude ranch in Santa Fe, he settled on the paths he wanted to take. He decided to become a Catholic; to marry Bunt Townsend, a young woman he had known for several years; and to give up medicine in order to write.

Following a simple wedding in New Orleans on November 6, 1946, and almost a year’s stay at Brinkwood (the Percy summer house near Sewanee, Tennessee), the couple returned to New Orleans where they began instruction in Catholicism. Reticent to explain his conversion, Percy usually replied, “What else is there?” In a more serious moment, however, he confided to an interviewer, “I took it as an intolerable state of affairs to have found myself in this life and in this age, which is a disaster by any calculation, without demanding a gift commensurate with the offense. So I demanded it.” During this stay in New Orleans, Percy discovered the works of Charles Sanders Peirce, an American semiotician and philosopher. Peircean theory proved to be an abiding interest and formed the basis of much of Percy’s own work in semiotics. It was also during this time that Percy began trying in earnest to write, though his resolve was undermined to some extent by his love for New Orleans, a city rich in distractions. In “New Orleans: Mon Amour,” Percy says New Orleans is what you would get if “Marseilles had been plucked up off the Midi, monkeyed with by Robert Moses and Hugh Hefner, and set down off John O’Croats in Scotland.” When life there proved “too seductive,” he, his wife, and their newly adopted baby daughter, Mary Pratt, moved to Covington, a small town outside of New Orleans reputed (falsely) to be the “second healthiest place in the world” and a place Percy felt would be congenial to his health, his writing, and his religion. Seven years after Mary Pratt’s adoption, the couple were surprised by the birth of a daughter whom they named Ann Boyd. When they discovered that Ann was deaf, the Percys devoted unlimited time and travel to seeking special teachers and programs for her. Although Percy had already begun his investigations into semiotics, Ann’s deafness intensified his study.

Walker Percy was in some ways a man paradoxically divided between his desire to be part of a group and his need for privacy. He joined a college fraternity; he was a member of a church, lunch groups, and book clubs; he settled in a Catholic community; he was the father of a debutante; and though uncomfortable instructing, he sought teaching opportunities mostly for the company such gatherings provided. Yet while seeking congenial society in religious, social, and literary contexts, Percy remained somewhat distant and self-contained. Despite efforts to immerse himself in the outside world, his natural reserve combined with his intellectual singularity worked to ensure that Percy remained essentially apart, even (or especially) in his own hamlet. As he became increasingly disenchanted with the town, he liked to joke, “though I have lived in Covington 30 years, the Budweizer distributor is better known.”

When queried about the possibilities of writing a memoir, Percy said he “couldn’t think of anything more boring.” If his life in Covington was to a large degree predictable, it hardly seems to have been boring, considering the vitality of his intellectual and creative existence. The achievements of his writing career alone are considerable: six novels and two books of essays. In 1962, he won the National Book Award for The Moviegoer and invitations, appointments, honorary degrees, and other prizes followed. Having received unstinting support from writers such as Shelby Foote, Jean Stafford, and Caroline Cordon, Percy was generous in assisting other writers and students of literature. Most notable was his pivotal role in getting A Confederacy of Dunces, a novel by deceased author John Kennedy O’Toole, published. Ironically, the book went on to win a Pulitzer, a prize that eluded Percy.

Fiction writing was Percy’s natural metier, but he did not settle into it altogether comfortably. Although his greatest achievements were literary, he seems to have derived the most satisfaction from his philosophical essays on language and symbol. When Flannery O’Connor complimented him on The Moviegoer and told him to “make up another story,” her words struck a chord and perhaps had a different effect than what she had intended. In his letters, Percy refers more than once to her comment and expresses doubt about the legitimacy of “making up stories” as though it were somehow an unworthy occupation for a grown man. In such moments of insecurity, Percy obviously yearned for the comfort, the definition, and the routine of a “real job” or “regular work.” At other times, he expresses such misgivings in terms of being torn between “thinking” (his serious work in linguistics) and “imagining” (“making up stories”). Even his particular brand of fiction—stories that work didactically to some greater good—reflect the author’s pragmatic bent. Thus, though he eschewed medicine as an occupation, Percy remained at heart a doctor, a man interested in effecting cures.

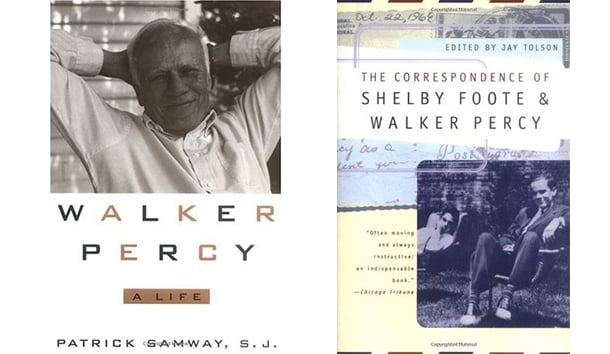

Patrick Samway’s Walker Percy: A Life is a dutiful compilation of data, but the biographer does not accomplish enough with his material. We learn of Percy’s struggles with depression, his double with alcohol, the dry spells in his marriage, but these difficulties never become substantially real. Part of the problem is that Samway’s prose style often lacks clarity and coherence. While the biographer provides ample facts, he seems at a loss where application and summation are concerned. His few attempts at interpretation result in feeble banalities. Commenting on Percy’s killer concentration, Samway says: “He found solace in the written word and could imaginatively explore the unknown worlds that books offer. In particular, Walker seems to have understood that poetry and fiction give us the second chance that life seems to deny us.” Such pedestrian writing bespeaks a superficial understanding. How, for example, does the notion that “his casual dress reflected his inner spirit and put people at ease” square with the fact that Percy was intensely shy, and what is a “casual” inner spirit anyway? Finally, the biographer’s use of the too familiar “Walker” throughout, though a minor flaw, is an indicative one.

The best that can be said of this book is that the author has avoided two of the biographical writer’s basic sins. Sam way does not distort or pervert the material to his own ends, nor does he indulge in posturing. His respect for his subject is apparent. Yet this same respect, perhaps, prompted him to drop subjects or omit details that might be embarrassing or hurtful to Percy’s family and friends, resulting in inconsequential detail mixed with curious silences on important issues, often leaving the reader dangling. Samway casually verifies suspicions later on in an aside, an irksome technique at best. While seeming to issue from a sense of delicacy, such omissions are counterbalanced by Samway’s unflinching discussion of Percy’s trouble with flatulence and his addiction to Metamucil. Although Jay Tolson’s 1992 biography. Walker Percy: Pilgrim in the Ruins, is unquestionably the better of the two. Walker Percy: A Life does offer a different approach, and thus an additional opportunity to view the life of an extraordinary thinker and writer. While Samway may not have a great understanding to impart to the reader, his subject does, and even the details of Walker Percy’s life are a full measure.

In the Lysis, Plato’s dialogue on friendship, Socrates says that he would rather have a good friend “than the best quail or cock to be found,” “than the gold of Darius,” or “Darius himself” A friendship sustaining to mind and spirit, of inestimable worth, was enjoyed by Walker Percy and Shelby Foote, as they themselves reveal in The Correspondence of Shelby Foote & Walker Percy, a collection of their letters edited by Jay Tolson. What is initially most striking in these letters is the differences between the two friends, Percy’s irony and circumspection providing an effective contrast to Foote’s exuberance and optimism as expressed in, among other things, their writing habits. Foote outlined his novels carefully before he wrote them, whereas Percy allowed his own to evolve more organically. Also, because Percy’s philosophical bent often led him into bogs of abstraction, fiction gave him a medium for embodying the ideas he had worked out in his mind; conversely, fiction gave Foote, a man centered in the concrete, a means of discovery. Yet their differences as men and artists helped to establish a compatibility that is captured in Percy’s reflection on their Greenville years; “We were each other’s college.”

In other ways, Percy and Foote were very similar. Tolson’s observations that they were “more observers than participants” and that “both were witty, prematurely cynical, irreverent, and generally attuned to each other’s humor” find confirmation in the letters. The two friends were consummate Southerners and outspoken civil rights supporters (Percy for religious rather than for sociological or legal reasons), and, though politically liberal, they were independent in their thinking, avoiding strict partisanship. Interestingly, each believed that National Review treated his work most thoughtfully; “Maybe we’re conservatives after all,” Percy adds wryly in passing. It must also be more than simple coincidence that Percy received The Ingersoll Foundation’s prestigious T.S. Eliot Award for Literature in 1987 and Foote won its Richard M. Weaver Award for Scholarly Letters a decade later.

The Foote-Percy correspondence in fact belongs predominantly to Foote, his letters being greater in number (Percy kept them from 1948, while Foote did not begin saving Percy’s side of the exchange until roughly 1970) as well as longer and more expansive. In addition to personal news and in-depth comment on his own work, Foote’s letters include lengthy discussions of books, movies, music, and writing. The breadth and depth of Foote’s reading (and re-reading) is astounding; he is invariably going through Proust or Dostoyevsky or Dante or whomever for the ninth or tenth time. Yet his greatest attention is often directed toward advising and encouraging Percy in his writing. Even after Percy won the National Book Award and seemed to be established, Foote continued to give his friend unflagging support (and admonishment, when he felt Percy needed it). If the reader finds Foote’s tone occasionally excessive, he is only seconding Foote himself, who, late in the correspondence, apologizes for his didacticism and counts Percy a “saint” for having put up with him. Otherwise, Foote is unfailingly charming and usually right (we can forgive him for his dismissal of Flannery O’Connor as a “minor-minor writer”). Among the liveliest passages in the book are his irreverent updates on his 20-yearlong Civil War project. On September 8, 1960, he writes, “By the end of the month I expect to have killed Stonewall Jackson dead as a mackeral”; on January 19, 1970, he is “finally back on pulse, crossing the Chattahoochee with Sherman and getting ready to send a bullet straight up James Birdseye McPherson’s ass. A good lodgment”; and by July 10, 1973, he is nearing the end: “I’m working like a fiend, cooking Bobby Lee’s goose but good.”

Even though they are fewer, shorter, and more improvisational, Percy’s letters have their own dramatic presence. Witty and self-deprecating, they are generally introspective. While Foote is self-assured, judging the world in terms of black and white, Percy is troubled by the grey. Tolson’s claim that the reader finishes the letters “understanding these two men almost as well as they understood each other” may overstate the case somewhat, but one certainly leaves the volume with a feeling for the personal intensity of each of these writers, and a strong impression of a deeply connected friendship spanning a period of 60 years.

[Walker Percy: A Life, by Patrick H. Samway, S.J. (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux) 506 pages, $35.00]

[The Correspondence of Shelby Foote & Walker Percy, edited by Jay Tolson (New York: W. W. Norton) 310 pages, $29.95]

Leave a Reply