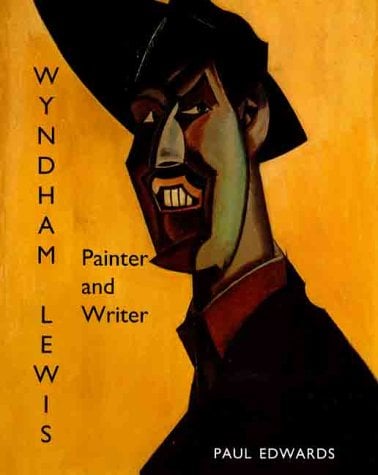

[Lewis: Painter and Writer, by Paul Edwards (New Haven and London: Yale University Press) 584 pp. $75.00]

Professor Edwards has set himself to a daunting task in taking on Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957). Lewis the painter is a difficult task for many reasons: first, because he attacked the British art establishment early on, trashing Roger Fry and Bloomsbury and later Kenneth Clark, thereby laying a groundwork of controversy and contempt; second, because his shattered career caused much of his early work to be lost and some of his later work to be less than excellent; and third, on account of the nature of much of that work (sometimes representational, sometimes abstract, but always lacking in obvious appeal and certainly no part of any school except perhaps Lewis’s own Vorticism). Edwards has shown Lewis’s graphic work to have been driven by his obsession with what we may call the modern metaphysical. In his paintings, we hover over Cartesian vortices, as Melville’s Ishmael did. Let me add (as if you could stop me) that Edwards’ treatment of Lewis’s graphic art is the most persuasive and instructive I have ever seen: well worth the price of admission. The comparison here would be with Walter Michel’s authoritative catalogue and Hugh Kenner’s essay in Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings (1971) as well as Richard Cork on Vorticism (1976), but Edwards’ analyses seem both superior and needed.

But though that is much, it is not all—far from it. Edwards has also addressed himself to Lewis the writer, of itself a challenging, even treacherous subject, again for a host of reasons, among them (1) that Lewis was (is) the most politically incorrect major author in modern British literature, having explored with brilliantly analytical hostility the meanings of feminism, the youth cult, homosexuality, the “gilded bolshevism” of the 20’s, and all the other idols of the Zeitgeist triumphant today; (2) that he puffed Adolf Hitler more than once in the early 30’s in a misguided attempt to avert a second world war; and (3) that Lewis sometimes published hastily and assembled his books badly, adding further damage to his reputation. Straightening all this out (50 books in 50 years) in what Carolyn Heilbrun has called “the Age of Woolf’ (yes, Virginia was one of Lewis’s favorite punching bags) is no task for the faint of heart.

Add to all the textual, aesthetic, and political problems the challenge of Lewis’s prophetic insight, idiosyncratic expression, and extensive historical and philosophical reading, and there is inherent difficulty in the complexity of the material and therefore in its exposition. Edwards has performed brilliantly and incorporated many new insights of his own, as well as of other recent critical and scholarly work. One more reason to have a copy of this book, then, is for the notes and bibliography, quite valuable in their own right. I must say that I regret that the comments on Lewis’s writing aren’t complete. Two of the stories in Rotting Hill are masterful, and The Red Priest has something going for it as well.

But never mind, for we come then to the point: The paintings and the writings were the product of one man, though not perhaps of one unified sensibility. The sense of crisis in Lewis’s work is not finally his but rather his modernist sense of our crisis. That crisis took many forms, religious, philosophical, aesthetic, and other; above all, it was that of human identity—both individual and in the mass—in the machine age. As we begin the 21st century, we can find no better explorer of the “metaphysics of the not-self than Wyndham Lewis. On the shelf beside Lewis’s best work (Tarr, The Childermass, Time and Western Man, The Apes of God, Snooty Baronet, The Revenge for Love, Malign Fiesta, and others: I am thinking of the scholarly editions of Black Sparrow Press), this integrated exposition by Paul Edwards has a valued and necessary place. I think I can close nicely with his own closing words:

[Lewis’s] work provides the most comprehensive critique we have of the Modernist urge to overcome our dereliction by violently breaking through to a realm of authenticity, a reality transcending our divided condition; driven by such urges himself, he yet knew that it was our privilege to be no more than imperfect imitators of that authenticity, and urged us to realize that we must be Apes of God rather than gods ourselves.

Leave a Reply