When Margaret Thatcher died last April, the obsequies were at times almost drowned by vitriolic voices celebrating her demise. There were howls of joy from old enemies, street parties, and a puerile campaign to make the Wizard of Oz song “Ding, Dong, The Witch Is Dead!” the top-selling pop single. (It failed, narrowly.) The extravagant hatred evinced shocked some people, but it was in a way an entirely suitable send-off for a woman who always loathed “consensus.” She may be the last Conservative whose demise will evoke more than a yawn.

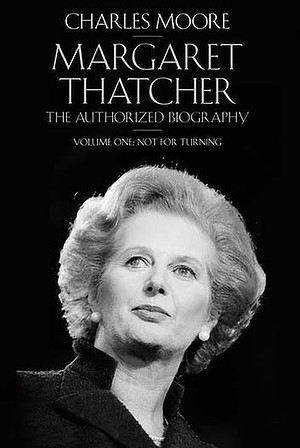

This is former Spectator and Daily Telegraph editor Charles Moore’s first book, but it is an assured production, steeped in its subject, judicious in its handling of history, colored by the author’s journalistic instinct for revealing and amusing anecdotes. In this first of two volumes, Moore follows his heroine from birth to what “may well have been the happiest moment in her life”: the October 1982 victory celebrations after the recapture of the Falklands. His heroine she may have been—which is why Lady Thatcher approached him to be her biographer, on the understanding that publication would be posthumous and that interviewees knew she would never read what they had said about her—but he maintains critical distance nevertheless. Fifty-four pages of footnotes refer the reader to innumerable interviews, and there is a seven-page bibliography, assembled over 16 years of what must have been at times an all-engrossing project for Mr. Moore, while he was incidentally editing Britain’s best-selling broadsheet. We will need to wait for the companion volume, Herself Alone, to get Moore’s assessment of her legacy, but for now, Not for Turning equips us admirably to understand who Lady Thatcher was as person and politician, why she was the way she was, and why she succeeded in many ways, as she fell short in others.

Moore’s researches were at times made more arduous by his subject, a naturally private person who was always, as he reflected in the Daily Telegraph after her death, “keen to efface the personal.” Her memoirs gloss over emotions or incidents about which we would like to know very much more, or which might lend “Thatcherism” greater coherence in retrospect than it possessed. But luckily she was intrinsically honest, and Moore early learned to read and interpret subtle signs: “All politicians often have to say things that conceal or avoid important facts. She certainly did this quite often; but she did it with a visible discomfort which often undermined her own subterfuge.”

This complex personage pushed into the world in 1925 and grew up above commercial premises in Grantham, Lincolnshire, a town even now a byword for provincialism, despite its having been Isaac Newton’s hometown. Home was one of two grocery shops run by her father, Alfred Roberts, who, when he wasn’t selling sausages to Midlandian burghers, was town mayor and a Methodist lay preacher. “If you get it from Roberts’s—you get the BEST!” was the shops’ slogan. Her parents’ rectitude, work ethic, and attention to detail were carried on by their daughter throughout her life.

School was preparation for a life of application. A contemporary remembered that “She always stood out because teenage girls don’t know where they’re going. She did.” Unsurprisingly, Margaret excelled in declaiming from sturdily middlebrow poets—Tennyson, Longfellow, Kipling, and Whitman. Serious too was her sojourn in Somerville, regarded as the cleverest of the female colleges in Oxford, where she read chemistry and thrived under a leftist principal.

The young Margaret Roberts, notwithstanding the pervasive progressive miasma, was already obstinately conservative, although she had not yet refined her particular brand. She joined the Oxford Union Conservative Association (OUCA) and became its president, and was coauthor of a pamphlet destined to be combed over by obsessives in later years. At that time the Conservative Party was a mass movement and a means of social mingling, and many people joined it for social as much as for political reasons, often to find a suitable spouse. Moore suggests that Margaret Thatcher, too, saw OUCA as an “opening of the door.” She took elocution lessons and met as many influential people as possible, always inveigling herself somehow onto the top table at dinners. Yet her letters to her parents and older sister, Muriel, are often apolitical, rarely mentioning the war, unexpectedly spotted with spelling mistakes, full of family, clothes, and rare romantic interests, the latter discussed in briskly British terms. When she first met Denis, her husband-to-be, she told Muriel that he was “a perfect gentleman. Not a very attractive creature.” (He remembered her almost equally coolly—“a nice-looking young woman, a bit overweight.”)

After graduation she worked in industry and in 1950 stood for Parliament for the first time in the solid Labour seat of Dartford in Kent. She conducted a dynamic campaign, characterized by her contribution to a debate hosted by the United Nations Association, which featured her Labour opponent Norman Dodds and other speakers even further left:

I gave them ten minutes of what I thought about their views! As a result Dodds wouldn’t speak to me afterwards and Lord and Lady S. [Strabolgi—an old Scottish title Italianized in the 16th century] went off without speaking as well.

She made an impressive 6,000-vote dent in the Labour majority. It is characteristic that at the count she told her activists that the next campaign would start the following morning.

Margaret Thatcher married Denis in 1951, the start of a quietly contented partnership that lasted until his death in 2003. As well as his earning capacity and a business brain useful whenever his wife needed to comprehend company documents, he brought to their alliance some social status, a large fund of common sense, and a willingness (even now rare among men) to take a back seat. Performing household tasks—she cooked when she could, and enjoyed tidying (an everyday application of what Edward Norman called her “pre-existing sense of neatness and order in society”)—assuaged the faint guilt she clearly felt at being something of a Bluestocking.

Needing to earn more money, she trained for and practiced at the bar, an experience that reinforced her near-mystical respect for law of all kinds. Thatcher later systematized this passion for precedents:

As a Methodist in Grantham, I learnt the laws of God. When I read chemistry at Oxford, I learnt the laws of science, which derive from the laws of God, and when I studied for the Bar, I learnt the laws of man.

Between work and family, she politicked tirelessly, resenting even holidays as wasted time. (There is a telling photo of her in this book, on holiday in the Hebrides in 1978, walking in business clothes along a beach, staring at her watch.)

In 1958, she applied for selection in the north London constituency of Finchley, where the electorate was approximately one-fifth Jewish. This suited her, perhaps predisposed to philosemitism by her Nonconformist upbringing, certainly always admiring of law-abiding, hard-working people, and she impressed from the start. At one selection committee meeting, an astute member whispered to another, “We’re looking at a future Prime Minister of England.” Later, she would be strongly influenced by Jewish thinkers like Milton Friedman, Keith Joseph, and Alfred Sherman (the latter a late fan of this journal) and was a strong (if not uncritical) supporter of Israel. Macmillan once joked that her cabinet contained “more Old Estonians than Old Etonians.” (Yet she also came under fire from constituents for upholding Oswald Mosley’s legal right to hold a rally in Trafalgar Square.) She was of course selected, then elected in the 1959 election, and in 1961 got a junior ministerial post as parliamentary undersecretary at the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance. Her anxiety to prove herself and achieve something was immediately evident; her minister grunted to the department’s top civil servant, “She’s trouble. What can we do to keep her busy?”

As the Kingdom lost its Empire, it also lost its way, and her party drifted directionlessly. Quite apart from the threats to order and freedom posed by different kinds of socialism, ranging from Soviet-funded Marxism to saccharine egalitarianism, the economy was dominated by sclerotic state-owned concerns, while attempts at reform were usually stymied by ultraleft trade unionists. There was a decline syndrome of spiraling spending, ballooning inflation, in-built inefficiency, and industrial (in)action. The Conservatives seemed powerless to act, or even to think, although monetarism was gaining ground among cleverer Tories. Thatcher was frustrated by the party’s unwillingness to engage in what she could see was an ideological rather than a mere electoral battle. Emblematic of Conservative complacency was the reaction of the free-market Economic Dining Club, whose members were reluctant to let her join, fearing she would dampen their masculine conviviality and compel them to engage in discussions before dinner.

On other matters, she was more old school—in favor of corporal and capital punishment, against pornography, drugs, and easier divorce. But she was never a reflexive moralizer, voting to legalize both homosexuality and abortion (the latter owing to her encounter with a despairing disabled child). Whatever her private views on any subject, she was then (and would always be) “trapped in moderation,” to borrow the title of one of Moore’s chapters—compelled to work within a framework in which the odds were always against her.

Natural allies lacked stomach—for example, businesses refused to help in the fight against the closed shop because they wished to avoid unpleasantness and a complicated alternative. Again, in the 1960’s and 70’s, even many Tories wanted comprehensive education, and although she managed to save 94 grammar schools while education secretary (1970-74), she was compelled to allow 3,286 comprehensives. Thatcher hated the egalitarian educational orthodoxy, although sometimes she had to defend it publicly. Moore cites an interview in which she claimed that primary schools were “much better . . . much more progressive,” while she was saying privately to aides that all those schools offered were “rag dolls and rolling on the floor.”

She had learned how to combine being a conviction politician with being a pragmatic politician—and to ensure that when she had been bounced into a course of action she should make her unhappiness known to the right-of-center grassroots. She was sincere, but she was also a superlative party manager. Yet she really tried. “You came out of a meeting with her,” one education official remembered, “feeling that you’d had three very hard sets of tennis.” But he remembered her fondly; she was unfailingly kind and generous to staff.

Good luck came to her aid when Ted Heath refused to take her leadership challenge seriously, and in 1975 Mrs. Thatcher took his place as Conservative leader, the first woman to lead a major Western political party. She reveled in the attention, and did not mind being hated. She was the last Conservative leader willing to endorse inequality—“Equity is a very much better principle than equality.” She attracted contumely even from her own advisors for supporting Ian Smith’s Rhodesia. Zbigniew Brzezinski was astounded to learn that she was “inclined to favour the white position”; in one speech she even said, “The whites will fight, and the whites will be right.” In the end, on Rhodesia as on so many other matters, she bowed to inevitability—but arguing fiercely as she retreated. She attended what despairing Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials called “disturbingly right-wing” meetings in America, building bonds that would be of material benefit during the Falklands War (although Moore is at pains not to hyperbolize the “special relationship”). In a famous interview in 1978, she infuriated the party establishment by speaking on immigration, a subject on which she had said little before, saying that many Britons feared “they might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.” But she hoovered up votes that would otherwise have gone to the National Front, then on the cusp of a popular breakthrough, and delivered huge swathes of the white working class into the Conservative camp. (Mrs. Thatcher did nothing substantive about immigration, although the numbers approved for citizenship dipped during the 80’s, from around 72,000 a year to around 54,000.)

The incompetence of her opponents helped propel her over the threshold of Downing Street in 1979, as “undoubtedly,” Moore writes, “the most truly conservative person . . . ever to reach No. 10 in the era of universal suffrage.” She was also almost certainly the last PM who would pay no attention to popular culture, or even the media—and who was so innocent that she once gave TV cameras the two-fingered V for victory sign the wrong way round.

Although Thatcher faced great resistance from within her own party—the so-called Wets who regarded her as vulgar—their intellectual incoherence gave her a great advantage. At times, however, she missed opportunities, perhaps partly out of relict deference to these grandees, certainly because she often acted intuitively rather than strategically. Her intellectual influencers rarely combined political intelligence with their incandescence, so she had to rely on less “sound” careerists who watered down her wishes—not that she was ever the anarchocapitalist many wailed she was. Little happened on the economic front until she and Geoffrey Howe pushed through the 1981 budget, largely against her cabinet and “expert” opinion, but as this volume ends the economic battles that would define her mostly lie ahead.

She was also under fire, almost literally, in Ulster. Mrs. Thatcher patrolled in uniform, Boadicea-like, with the troops in South Armagh’s “Bandit Country,” and sent handwritten letters to the families of soldiers killed in the line of duty; her Unionism was all the more impassioned for the loss of one of her closest friends and allies, Airey Neave, to an INLA bomb. She found herself having to deal with rampant terrorism, hunger strikers, the oleaginous Charles Haughey, international opinion, and her own diplomats; one can see how, just a few years later, she would sign the Anglo-Irish Agreement against her own instincts.

Moore provides other portents of future failures—such as her relative lack of interest in the European Union, or her reaction to the Brixton riots of 1981, a typical Thatcher combination of strong rhetoric followed by the appointment of a left-wing judge to conduct the inquiry. Trapped not just in moderation, Thatcher was becoming enmeshed, too, in political correctness. She was also making enemies of many senior Tories through sheer brusquerie. Charles Moore is setting the scene for eight years of effort and isolation leading to treachery, talismanic exile, and finally sad dotage when “The Lady” appeared in public only infrequently, a tiny ex-titan towered over by men who affected not to notice that her famous features had fallen to one side, and her lipstick was askew.

But for now, we close the book with the curtain on Act I and Mrs. Thatcher’s greatest triumph—the 74 days between April and June 1982 when the Falklands were in global play and the PM was thrown upon her inner resources and not found wanting, guided to victory by her personal compass and her willingness to trust to the courage and skill of the armed forces. At the memorial service at St. Paul’s that October, she stood, funereal and indomitable, beneath Wren’s great dome, determined that the military, not she, should take the credit, while the Whispering Gallery within the Cathedral and outside was alive with patriotic approbation. For a moment, the Iron Lady stood as an evocation of Elizabeth I, the personification of a patria both beautiful and doomed.

[Margaret Thatcher: Not for Turning, by Charles Moore (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) 859 pp., $35.00]

Leave a Reply