A new historical analysis of administrative law exposes FDR’s suppression of civil liberties.

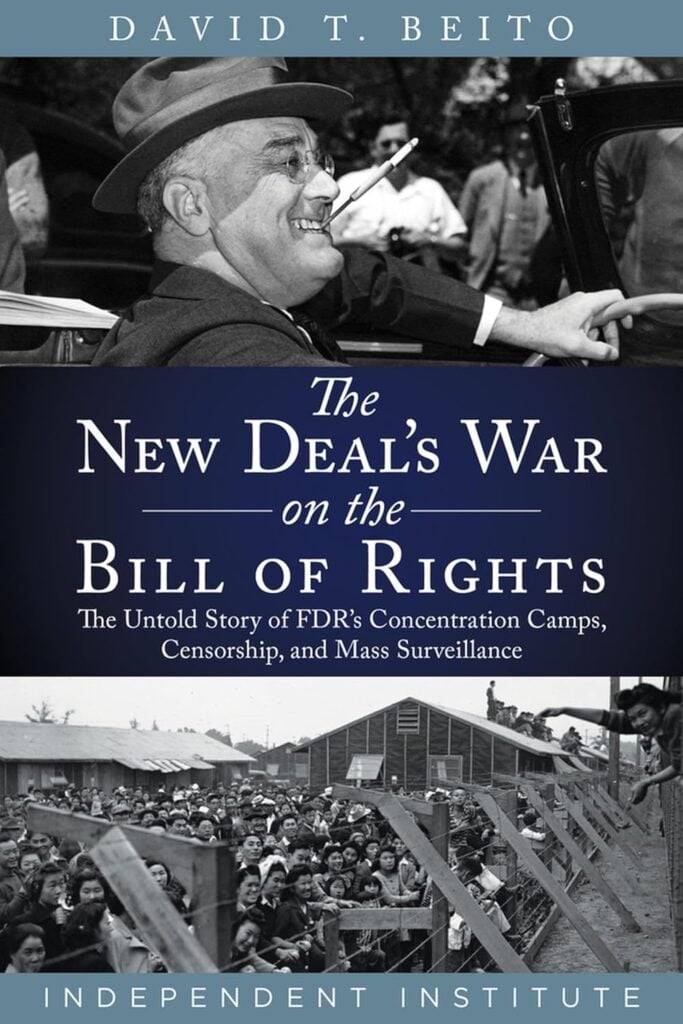

The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR’s Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance

by David T. Beito

Independent Institute

404 pp., $26.95

Given the accumulating evidence of corruption within the executive branch of the United States government, it is hard not to believe that we are living through the worst of times, and that the American dream of virtuous republican government is now doomed.

Certainly, this may be the case. But it is more probable (as our framers understood) that republics, since the days of Rome, tend gradually toward corruption. It’s a miracle, then, that any elements of American rule of law continue to operate. Still, considering that we have weathered significant corruption in the past, there is some hope that we will muddle through. David T. Beito’s review of the questionable legal conduct of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration offers just that notion.

FDR, of course, is a hero in the conventional progressive narrative. His fortitude and virtue are said to have saved American capitalism from collapse during the Great Depression and his conduct as a wartime leader is characterized as instrumental in preserving democracy (or something like it) in Western Europe. Revisionist economic historians have suggested that the New Deal, and the concomitant shifting of control to centralized agencies, prolonged distress in this country. Beito’s account of what amounted to American concentration camps, wartime censorship, mass surveillance, and misuse of executive branch agencies (such as the IRS) for partisan political purposes further impugns the claim that FDR was a man of virtue.

The incarceration of many thousands of Americans of Japanese ancestry (known as Nisei or “the second generation”) during World War II is well-known. The unconstitutional nature of that move now seems to be conventional wisdom, although at the time the Supreme Court, in the infamous Korematsu case, upheld the internment camps as a wartime necessity. What was not generally known then, and what Beito makes clear now, is the opposition to that policy on the part of many executive branch officials. The opposition was successfully overridden in no small part by the personal prejudice President Roosevelt and the First Lady held against the Japanese race.

What makes this account even more valuable than the discussion of the detainment of the Nisei, however, is the exposure of FDR’s essentially venal and covert attempts to erode or cancel the constitutional protections of free speech and other elements of the Bill of Rights during his unprecedented four terms in office.

Senator Hugo L. Black, a staunch First Amendment proponent whom FDR appointed to the Supreme Court, comes off here during his congressional career as something less than libertarian. The book’s first chapter reviews Black’s efforts as chairman of the Senate committee ostensibly in charge of regulating lobbying. In reality, he engaged in efforts to intimidate and silence critics of FDR and the New Deal.

One of the signal failings of legal education in the United States for the last century-and-a-half is that we train lawyers to concentrate on the opinions of appellate courts. Students are made to appreciate the nuances of constitutional interpretation and the conflicting strands in the basic doctrines of contracts, torts, property, and civil procedure. Unfortunately, we don’t teach budding lawyers what happens in legislatures, the source of much of our law, since statutes and the conduct of statutorily created administrative agencies have much more effect on our lives than court decisions. Beito’s book, in other words, is a rare look at how the sausage is made. And it is not a pretty picture.

The Black committee’s activities were ostensibly justified by a purported need to legislate in the area of regulation of lobbyists. It claimed the power to examine millions of telegrams sent to and from activists, journalists, and lawyers, and, with the cooperation of the IRS, the tax returns of administration enemies (a latter-day tactic first employed at the instigation of FDR). Not only was this unprecedented governmental surveillance, but the Black committee, with the likely covert support (and probably aid) from the White House, enthusiastically smeared administration opponents with charges of racism and anti-Semitism. As Beito explains, these prejudicial failings could also be laid at the feet of FDR himself.

The courts reined in the worst excesses of the Black committee. As time went by, the committee was increasingly subject to press and pundit excoriation for violations of privacy. But, unreported in most histories of the era was the damage done to individual reputations and the silencing of individual critics. Black’s dubious behavior was rewarded by his appointment to the Supreme Court, where he ironically became the hero of civil libertarians.

As Beito shows, Black’s successor as Senate committee chairman, Sherman Minton, though less celebrated as a judicial giant,was equally effective at using investigative means for silencing and harassing New Deal critics. Harry Truman later rewarded Minton with an appointment to the Supreme Court. In a spin on the ironic aphorism, these revisionist New Deal ministrations demonstrate that, in politics, no bad deed goes unrewarded.

The Black and Minton committees, with the encouragement of the president, then engaged in unprecedented and abusive surveillance of the Roosevelt administration’s critics. It often had the desired effect of neutralizing or silencing them. Yet even more effective were the administration’s efforts through newly created administrative agencies, such as the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), to promulgate the administration’s views and to discourage opposition. Unearthing a little-known episode in media history, Beito shows both how FDR monopolized and weaponized the popular new radio technology, and how his government’s monitoring of that medium empowered him, by the FRC’s purported regulation in the “public interest,” to censor critics.

The FRC predated the Roosevelt administration. The New Deal champions built upon prior efforts to create a different model for ownership of the airwaves from our usual conceptions of private property. Based on the argument that the radio frequencies were a “limited spectrum,” regulation was purportedly justified so that all might enjoy access. As has repeatedly happened with administrative agencies, however, Beito shows how “regulatory capture” occurred. The airwaves were soon controlled by the largest broadcasters, who carefully maintained their hegemony by operating in a way congenial to the administration.

We can understand Beito’s book as an examination of the origins of the current administrative state, whose nearly unchecked power controls the flow of information, monitors the citizenry, and silences critics. The story Beito tells is one of the triumphs of the executive branch over its critics, with only sporadically effective protection of civil liberties by nongovernmental institutions such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the American Bar Association. There are now, of course, many more media outlets. The internet has created an ability for communicating dissent unimaginable to Americans in FDR’s time.

Regrettably, the government has grown exponentially at the same time and the challenge now is somehow to diminish the power of the federal Leviathan. It is beyond the scope of Beito’s book to suggest how to tame the deep state. But the occasional descriptions of the brave reporters, publishers, pundits, and lawyers who persevered in their attempts to battle the increasingly arbitrary and autocratic demands of the New Dealers, and of FDR himself, offer at least some inspiration.

Beito’s treatment of the World War II homefront is probably one of the most thorough accounts of disgraceful racial discrimination ever conducted by an administration, as Americans of Japanese dissent were deprived of all their civil rights, and interned far from their homes. He splendidly recounts zealous prosecutors who, in an effort to silence FDR’s wartime critics, employed dubious means to tar opponents with sedition.

His retelling clearly carries implications for our own time. It is a tale of man’s inhumanity to man, but also a valuable cautionary account and a rare demonstration of how the histories of legislation and administrative law should be written.

In Chronicles’ history the caution in Psalm 146, the original motto of the magazine’s publisher, has loomed large: “Put not your faith in princes.” Read at the most general level, this biblical admonition simply means that salvation does not come from political leaders, but rather from God working through our institutions of religion, and, perhaps, from the work of the Holy Spirit in our literature and culture.

Conceivably, there is still noble and useful work to be done by transformative politics. But in our own time, when the country is dominated by a nearly intractable administrative state, Beito’s book exposing the troubling underbelly of the New Deal stands as a timely reminder that the Psalmist got it right.

Leave a Reply