In Vienna, during the decade before the Great War, an astounding concentration of creative genius coincided with the final stages of political collapse. The work of Hofmannsthal, Musil, Broch, Schnitzler, Kraus, Werfel, and Zweig in literature; Mahler, Wolf, and Schönberg in music; Krafft-Ebing and Freud in psychology; Wittgenstein and Buber in philosophy; Schiele and Kokoschka in art: These suggested that Austria had achieved self-awareness at the very moment of dissolution. As Musil wrote: “Yes, maybe Kakania [Austria] was, despite much which speaks to the contrary, a country for geniuses; and probably that is another reason that it succumbed.”

Vienna represented a state of mind in a state of siege. As the monarchy tottered toward extinction, it desperately maintained the trappings of empire that emphasized social pretense and external appearances, elaborate titles and gradations of power. The traditional Austrian attitudes—sentimentality, nostalgia, lighthearted aestheticism, love of spectacle, fondness for the countryside, indifference to social reform, and passivity toward bureaucracy—mingled uneasily with more modern currents: the protests against censorship and rigid sexual conventions, the alienation of intellectuals and a high suicide rate, the nationalist and antisemitic movements. Karl Kraus ironically called Austria, with its quixotic mixture of repression and freedom, “an isolation cell in which one was allowed to scream.”

The most brilliant artist produced by this paradoxical background was Gustav Klimt (1862-1918). Like Freud, he tried to free sexuality from the constraints of a normative culture and portrayed women engaging in lesbian love and erotic ecstasy. The son of a gold-engraver from a lower-middle-class suburb of Vienna, he had only an elementary-school education, but was well trained at the School of Applied Arts. Though he produced 230 paintings and 4,000 drawings, he was notoriously reluctant to speak about himself, his technique, or his art. He was mainly supported by wealthy Jewish patrons and became infatuated with the teenaged Alma Schindler, who later married Mahler, Gropius, and Werfel. Though deeply attached to his favorite model, Emilie Flöge, he fathered 14 children with various women.

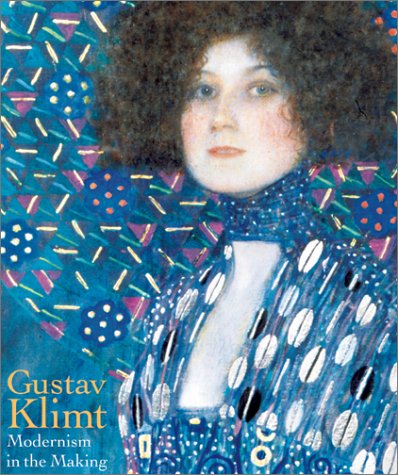

This sumptuous catalogue (with 330 illustrations, including 190 in full color), prepared for an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Ottawa, traces Klimt’s astonishing stylistic transformation from a traditional 19th-century academic painter to a celebrator of unreality in the Keatsian “realms of gold.” In 1923, a perceptive critic wrote that Klimt

is conceivable only in Vienna, better still in Budapest or Constantinople. His spirit is entirely Oriental. Eroticism plays a dominant role in his art, and his taste for women is rather Turkish. He is inspired by the decoration of Persian vases and oriental carpets, and especially delights in the gold and silver of his canvases.

The catalogue, after a brief introduction, presents essays by diverse hands on Klimt’s conflict between tradition and modernism, his seismic reputation, his use of applied arts, his drawings, a complete description of the 36 paintings in the exhibition (which repeats information from the essays), and an extensive chronology and bibliography. Several of the essays, translated from the German academic style, are learned but rather heavy-going.

Klimt was the leader of the fin-de-siècle Secession movement—the Austrian equivalent of German Jugendstil, French art nouveau, and English Aestheticism. During the first decade of the 20th century, he produced an impressive, and often controversial, series of masterpieces. Commissioned by the University of Vienna to do an allegorical painting of Medicine, Klimt created a nude figure who seems to exalt in the public display of her sexuality. The faculty fiercely condemned his work and “demanded that if the figure in question had to be female, then it should be clothed, or if it was unavoidable that it be naked, then it should be a male figure instead.” After years of protracted argument, Klimt finally renounced the commission. His Hostile Powers, part of a Beethoven exhibition in 1902, featured a pot-bellied hermaphrodite based on Aubrey Beardsley’s Ali Baba (l897). One clinically minded critic exclaimed:

Klimt has once again produced a work of art that calls for a doctor and two keepers. His frescoes would fit well in a psychiatric institute. The representation of “Lewdness” on the back wall is the last word in obscenity.

Klimt had seen the Byzantine mosaics in Venice and Ravenna and adopted their two-dimensional pattern of abstract ornamental forms. In Goldfish (To My Critics), a woman seductively displays her swirling tresses and comely bottom against a flat metallic background of watery flowers and flowery waters. In Water Serpents, swooning subaqueous anorexics float in a trancelike state. His legacy to Viennese Expressionism was the emaciated woman with “protruding pelvis and rib cage, provocatively red hair and lips, long and slender legs.”

In his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the subject is imprisoned in the stiff Byzantine richness and sensuous serpentine swirls of a vibrant cloth of gold. In Expectations, an almond-eyed, high-foreheaded, lacquered-haired, heavily bangled beauty, with contorted Balinese hand gestures, hides, like a camouflaged animal, between a stiff brocaded gown and a vertiginous tapestry. As Baudelaire wrote of these dazzling femmes fatales in “Sed Non Satiata,” in Les Fleurs du mal:

Her polished eyes are wrought of hypnotic minerals,

And in that strange symbolic nature,

In which unviolated angel and sphinx of old unite,

Made all of gold and steel and light and diamonds.

Forever glittering, like a useless star,

Lies the frigid majesty of the sterile woman.

Death and Life, like so many of Klimt’s works, contains the threat of morbidity and shows the skull beneath the skin. As Klimt wrote of Hope I: “Everything is ugly: she is, and what she sees—only within her is there beauty growing, hope. And her eyes say that.” In his portrait of the nine-year-old Mäda Primavesi, the precocious child stands, in a white dress, against a lavender background. With legs apart, hand on hip, and a defiant gaze, she confronts the viewer with an unsettling mixture of engaging innocence and sexual sophistication.

Judith II portrays a stunningly beautiful, bare-breasted woman—head jutting forward with operatic intensity and bejeweled hands clutching at the rich brocade above the severed head of her victim. But Klimt’s masterpiece, and most famous painting, is undoubtedly The Kiss (1908). The lovers’ bare faces and hands protrude, as in a Byzantine icon, from a flat decorative envelope. The woman kneels, as in prayer, on a rich bed of flowers as strings of gold leaves trail from her golden cape. Like Hedda Gabler, she wears “vine leaves in her hair.” The man gently turns her head sideways and kisses her cheek. The subtle arrangement of their four hands and the sensual outline of her body suggest an erotic swoon.

Scholars have suggested Egyptian, Byzantine, Turkish, Persian, Japanese, and Korean—as well as contemporary—influences on Klimt. But no one has mentioned the all-pervasive influence of Gustave Moreau. J.-K. Huysmans’ precious description in Against the Grain (1884) of Moreau’s Salomé—whom Klimt also painted—applies with equal force to the opulence of Klimt’s art:

across her triumphal robe, sewn with pearls, patterned with silver, spangled with gold, the jeweled cuirass, of which every chain is a precious stone, seems to be ablaze with little snakes of fire, swarming over the matte flesh, over the tea-rose skin, like gorgeous insects with dazzling shards, mottled with carmine, spotted with pale yellow, speckled with steel blue, striped with peacock green.

[Gustav Klimt: Modernism in the Making, edited by Colin Bailey (New York: Harry Abrams) 239 pp., $60.00]

Leave a Reply