Years ago, when Parker Tyler memorably instructed us in the magic and myth of the movies, he indicated something about the archetypal power of film and the status of the stars as our own popular pantheon. The godlike qualities of star power were made manifest when Errol Flynn personified them as the ultimate swashbuckling man in tights, and even more as the object of lurid publicity, lubricious gossip, and sinister speculation. The twilight of the gods that we associate with Gloria Swanson-as-Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (1950) was perhaps even more tragically personified by Flynn when he paid the price for his compulsive dissipation, dying in Vancouver in 1959 of a heart attack at the age of 50. Flynn’s disintegration was so complete that his death was a good career move; at the end, he had no place to go, except to a Valhalla of celluloid. Flynn, who had wanted to be buried under an oak tree on his Jamaica estate, wound up instead in the Garden of Everlasting Peace in Forest Lawn, his casket covered in yellow roses, and his eulogy intoned by Jack Warner. The contrast between his humble wish and the cornball reality points up the contradictions that haunted his life.

Errol Flynn excelled at adventure movies of the type that Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. and Jr., had established. We remember him swinging on ropes, dueling with Basil Rathbone or someone, and always winning, and generally hamming it up in Captain Blood (1935) and The Sea Hawk (1940), two of his best films. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), a pseudomedieval romance and one of the best movies ever made for the young, is delicious in its precise fantasy and outrageous in its chivalric inversion of the truth of Flynn’s character. (Flynn’s charm saves this movie from itself.) We also remember him in a lot of bad movies, such as almost all of his Westerns. When he wasn’t at sea, this polo player was often on a horse, as in The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), or Santa Fe Trail (1940), or They Died With Their Boots On (1942). Who else but Flynn could have played the Earl of Essex, Don Juan, George Custer, and Jeb Stuart?

His stardom notwithstanding, Flynn was largely wasted in films. He hardly ever got to act—hardly ever had a role with an edge or appeared in a great film. He knew that, and he hated himself for it. In the end, however, he got to play “himself”—that is, he was cast as a self-destructive wastrel in The Sun Also Rises (1957) and stole the movie from Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner. In Too Much, Too Soon (1958), he played his own late friend, John Barrymore, whose follies he imitated in life. And in The Roots of Heaven (1958), he was again an aging alcoholic in another memorable performance. Flynn showed that, if he had had the opportunities, he could have done much more as an actor than rehashing the stereotype he was constrained to play on film. The stereotype he made of himself in life is another matter.

The story is fascinating and has been treated many times, most notably by Errol Flynn himself in My Wicked, Wicked Ways (dictated to Earl Conrad and published posthumously in 1959), the best autobiography that ever came out of Hollywood. Errol Flynn was a novelist and a journalist, quite well read and insatiably curious. His intelligence and sensitivity come out on film sometimes, and even his swashbuckling had a basis in truth. As an obsessive sailor and yachtsman, he really was, for example, the “Sea Hawk” of the movies; he was also the best tennis player in Hollywood, playing charity exhibition matches with Big Bill Tilden and Don Budge.

Notorious for his womanizing, Flynn was accused of two counts of statutory rape in a sensational trial in 1942. The jury, three-fourths female, acquitted him, but the experience scarred the psyche of Errol Flynn. He never stabilized his relationships with women; Jeffrey Meyers, in his treatment of familiar material, has emphasized that point. Flynn hated his mother and was neglected by his father. He treated all women as if they were as mean and stupid as he thought his mother had been. He only occasionally lived with any one of his three wives and confessed that he could love only men, by which he meant his drinking buddies.

Flynn neglected his children, though he loved them. His eldest, Sean, would try to fill the vacuum by imitating his legendary father. He was in like Flynn with the girls and had roles in Son of Captain Blood (1962) and other third-rate movies, but he could not be satisfied with that, any more than his father had been. Always pushing the edge, he met his end in 1970 as a photographer in an obscure incident, which has been much speculated about, in the Vietnam War. Jeffrey Meyers seems to have the last word about the mysterious death of Sean Flynn.

And he probably has the last word about Errol Flynn as well. Rarely (if ever) has a Hollywood star received such incisive treatment as Meyers gives to his primary subject, whom he treats shrewdly and analytically. Meyers has used his powerful research skills, his intellectual acumen, and his literary erudition to punch through the usual Hollywood nonsense, and, about Flynn, there has been an unusual amount of nonsense. Always maintaining perspective, and both sympathizing with and judging his dual subjects, Jeffrey Meyers has achieved a depth of treatment in a glossy, glamorous context. He demonstrates how, for both Flynns, the klieg lights only illuminated the way to a heart of darkness.

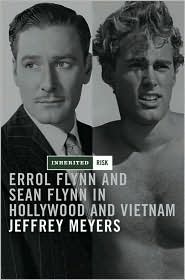

[Inherited Risk: Errol and Sean Flynn in Hollywood and Vietnam, by Jeffrey Meyers (New York: Simon & Schuster) 368 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply