Sideswiped by a car, Randall Jarrell died 34 years ago at the age of 51. That he has remained a presence as a writer and even as a man is vividly testified to by these books, which bring back a lot of memories, and different kinds of memories. Randall Jarrell was a force, even a star of the literary firmament, and when his books came out they were read and they were reacted to, though not always with precision. I remember an undergraduate poet asking me, in 1964, “Have you read The Owl by John Crowe Ransom?” I was able to return, “Are you referring to The Bat-Poet by Randall Jarrell?” Since then, I believe, that once-young poet, a disciple of Yvor Winters, has been a political scientist.

Randall Jarrell’s death in 1965 was a great loss, a particular and even peculiar one. Because of a mental breakdown he had suffered before the disaster, there has been a widespread conviction that actually he committed suicide. Jarrell’s widow, in her memoir, has argued effectively that the circumstances show his death to have been an accident, not self-destruction. Jarrell’s biographer, William II. Pritchard (Randall Jarrell, A Literary Life [1990]), declared that the exact nature of his death remains unknowable. However that may be, Jarrell’s death entangled him forever in the context of the 60’s, confessional poetry, and the unambiguous suicides of other poets, such as Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, and Ann Sexton.

But I believe that there was another problematic aspect of Jarrell’s death which has not been explored, and that is the matter of its “timing” in the larger cultural context. I find it hard to believe that Jarrell could have remained his old self (not that there was only one of them), both poised and open, in the coarsening that was mega-magnified in the 60’s: ranting against the Vietnamese war, Allen Ginsberg, “howling poetry,” Woodstock, and all the rest of it. If we had Randall Jarrell around today at the age of 85, would he be feebly directing his walker toward a hip-hop poetry slam? I somehow doubt this.

Well, these two books remind us of what all the fuss was about. Mary Jarrell’s memoir gives us an intimate portrait of the man, the poet at home, the writer, the friend. Her book is a fine example of its kind, and it will make its way onto many a shelf beside her own edition of Jarrell’s Letters (1985) and Pritchard’s biography. Through her book and others, we do have Randall Jarrell available to us today, and that is an enrichment of possibility that is both welcome and needed.

Brad Leithauser’s edition of Jarrell’s essays will stand as the collection for our time of Jarrell’s statements on poetry and culture. In the 1950’s, Randall Jarrell was the preeminent reviewer of poetry in this country, and he was probably the best we have had since Edgar Allan Poe. But he was more than that. Certain of his essays are unforgettable statements about the cultural situation of America: “A Sad I Heart at the Supermarket,” “The Obscurity of the Poet,” “The Age of Criticism,” and others are as exciting to read today as they were when they first appeared. More specifically focused pieces, like “To the Laodiceans” on Robert Frost, “Some Lines from Whitman,” and his speculative remarks on T.S. Eliot in “Fifty Years of American Poetry,” remind us of a remarkably simple truth: Randall Jarrell did more to establish our understanding of Frost and Whitman and Eliot than any other critic did.

Not everything is as we would wish it, perhaps. Jarrell did not quite go far enough on Wallace Stevens (R.P. Blackmur did); his essays on Kipling don’t quite get to the point, and sometimes Jarrell’s enthusiasms were excessive. At others, indeed, his lack of enthusiasm was equally so. I think he was wrong about Richard Wilbur and he was unjust to Roy Campbell, who was a great translator and occasionally “struck by lightning”—Jarrell’s definition of poetic success. Nevertheless, for wit, for perception, for passion, Jarrell’s essays can’t be beat. They are so good they can be read for the sheer pleasure of the experience, regardless of topic. Is it possible that his essays on poetry are better even than his poems? So it seems. In addition to which, Jarrell’s one irovel. Pictures From an Institution (1954), remains a delightful satire and a brilliant performance that makes us wonder not so much at what Jarrell could have done as at what he did.

Today, something of Jarrell’s role is performed by people as various as Dana Gioia, Helen Vendler, and Brad Leithauser himself; Daniel Hoffman is an utterly accomplished poet and critic and academic. Looking back at the parabola of Hie career of Randall Jarrell, we can see that his function was necessary, coming out of the 30’s and the background of the New Criticism as he did, writing war poems in the 40’s, attacking Eisenhower’s America in the 50’s for its complacency and philistinism, beating the drum for poetry itself, writing poetry all the way, and, in the 60’s, losing his edge before the end. He was as necessary as he was ornamental, and his career, which includes self-contradictions and shortcomings, was a register of the American imagination and of American possibility. Only an American could have gone as ga-ga over Europe as he did, because only an American would have needed to. Translating Rilke and Goethe, Randall Jarrell instinctively flinched from the implications of his own celebrations of Whitman and William Carlos Williams. Jarrell’s stressed sensibility, like that of James and Twain and Faulkner, showed once again that to be an American is a complex fate. That’s only one reason why, more than three decades after his passing, we still need him.

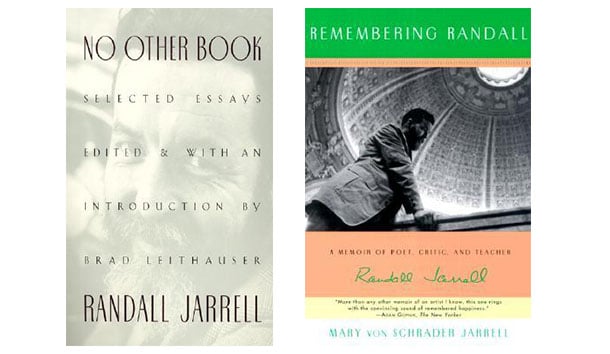

[No Other Book: Selected Essays by Randall Jarrell, Edited by Brad Leithauser (New York: HarperCollins) 376 pp., $27.50]

[Remembering Randall: A Memoir of Poet, Critic, and Teacher Randall Jarrell, by Mary von Schrader Jarrell (New York: HarperCollins) 171 pp., $22.00]

Leave a Reply