Fifty years ago, Indiana University professor Alfred Kinsey launched what was perhaps the first salvo in the Sexual Revolution. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, the work of Kinsey, Wardell Pomero), and Clyde Martin, hit postwar America like a sucker punch. Claiming that 85 percent of American males engaged in premarital sex, 70 percent had paid for sex with prostitutes, and between 10 percent and 37 percent were homosexual, the Kinsey Report revolutionized American law, culture, education, and a host of other areas. Critics of the report were to Kinsey what the Church was to Galileo. Kinsey was, after all, a “scientist.”

The picture of Kinsey that has been passed on by college texts and popular histories is that of the disinterested scientist whose research is unimpeachable. In David Halberstam’s The Fifties, Kinsey is “prudish,” “old fashioned,” and “the very embodiment of Middle American square.” Rutgers University professor William O’Neill praises Kinsey in American High as a “hero of science”; those who pressured the Rockefeller Foundation to cut his funding won “a victory for small mindedness.” William Manchester’s Kinsey in The Glory and the Dream is “an objective investigator,” “a stickler for explicit detail,” and a “disciple of truth.” “As a scientist,” said Manchester, “[Kinsey] had naturally played no favorites.”

Kinsey, as we know now, was a very different kind of “scientist.” A homosexual, a wife-swapper, a sadomasochist, and perhaps a pedophile, Kinsey was much more involved in his work than the keepers of the tablets would have us believe. The real Kinsey loaned his wife out to other men. His attic served as a personal pornographic movie studio. His fellow researchers, Pomeroy and Martin, also served as his sex partners. So powerful was Kinsey’s addiction to masochism that an incident where he strung a rope around a pipe, tied the noose around his genitals, and leapt off a chair hospitalized him for weeks and may have helped cut his life short.

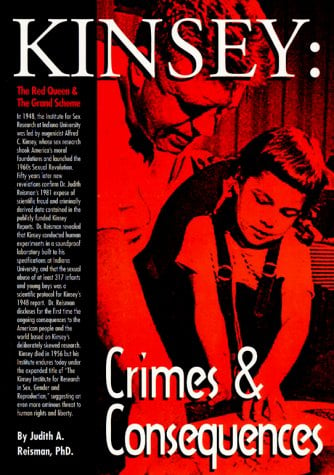

Kinsey’s bizarre personal life provides a motive for why he attempted to uproot the sexual mores of mid-century America. Kinsey: Crimes & Consequences, however, demonstrates just how he skewed his data to get the results he desired.

Although the total number of men he studied is in dispute (estimates range from 4,100 to 6,300), at least 1,400 members of the sample group were prison inmates. For Kinsey and his fellow researchers, basing their survey on the inhabitants of an environment that is a notorious breeding ground for perversion was still not enough to skew the data to their satisfaction. By developing key contacts in the urban gay subcultures of Chicago, New York, and other big cities, Kinsey was able to interview hundreds of homosexuals—and procure sexual liaisons for himself.

Reisman demonstrates that this same kind of statistical trickery is pervasive throughout his study of women. Prostitutes, for instance, were reclassified as “married women” in Sexual Behavior in the Human Female.

The keystone of Reisman’s work, however, continues to be Kinsey’s role in the abuse of hundreds of children. Attempting to prove that humans are sexual from birth, Kinsey collected data on at least 324 (and perhaps as many as 2,000) children. Infants as young as five months old, said Kinsey, achieve “orgasm” after being stimulated by “partners.” Symptoms of sexual climax for young children, Kinsey claimed, often included “sobbing,” “violent cries,” “loss of color,” and an “abundance of tears.”

Kinsey and his apostles have made contradictory claims concerning the number of child-molesters employed to produce this data. It is quite possible that Kinsey—a longtime counselor for such groups as the Boy Scouts and the YMCA —was a prime “observer” and source of information. While it is important to know who Kinsey’s trained observers were, Reisman also asks the more important question: “Where are the children today?”

To this day, Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute remains clouded in secrecy. Concerning “interviews” with small girls, Reisman wonders, “If, as the Kinsey team claimed, a parent was always present during the interview between ‘Uncle Kinsey’ and ‘Uncle Pomeroy and the small girl, and if all of every subject is in secret code in the Institute data base, as they claimed, why are these children not traceable?”

Despite having his work thoroughly discredited, Kinsey is still the ground from which most modern sex education is rooted. Reisman notes that “almost all AIDS and sex education in elementary, secondary, college, graduate and post-graduate school base their sex education curricula on the Kinsejan ‘variant’ model.” That a man who stamped his imprimatur on sex between adults and children would exert a prime influence on the sexual education of children does not speak well for America’s schools.

Nearly two decades since her address exposing Kinsey’s role in child abuse at the World Congress of Sexology in Jerusalem, Reisman continues to serve as an agent of truth. While much attention has been given to James Jones’s new Kinsey biography, Reisman’s Kinsey: Crimes & Consequences demonstrates that Jones, a former Kinsey Institute employee, conceals more than he reveals.

From Thomas Jefferson to J. Edgar Hoover, the sex lives (both real and imagined) of prominent Americans have become an obsession of modern academics. Yet Kinsey, the very man who would merit such an investigation most, has been ignored. Academics, feeling an ideological kinship with Kinsey, have therefore balked at debunking him.

A half-century after issuing his first sex study, Alfred Kinsey and his work have been uncovered as a fraud. Will it take another 50 years for educators to begin to take notice?

[Kinsey: Crimes & Consequences, by Judith A. Reisman (Arlington, Virginia: First Principles Press) 323 pp., $24.95]

Leave a Reply