My generation is perhaps the last to whom the figure of Aleksandr Sol-zhe-nitsyn looms as large as a legend. I have vague, hazy recollections as a boy, and as a teenager, of the man in the news who was depicted as a hero against Soviet totalitarianism. I was eight when Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers’ Union, nine when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and thirteen when he was forced into exile—first in Switzerland, and then in the United States. Back then, all that I really knew about the Russian was that he was famous. His picture was as familiar to me as that of the most famous politicians. His imposing beard, his stern expression, and his lofty brow made him instantly recognizable. He was, to employ the modern inane label, a celebrity. It was only later, when I read The Gulag Archipelago around the age of 17, that I fully realized that the lofty brow was also a highbrow, that the imposing presence had as much to do with the wisdom of what he said as with the heroism with which he said it. And when I read Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, at around the same time, it struck me that Solzhenitsyn was a real-life Winston Smith, except that the real-life version had succeeded, against all the seemingly insuperable odds, to defeat Big Brother. Fact was not merely stranger than fiction; it had a happier ending! With these experiences enshrined in my memories of him, it is easy to imagine how I felt, many years later, when Solzhenitsyn walked into the room, at his home near Moscow, to be interviewed by me for my biography of him. I was in the presence of a living icon.

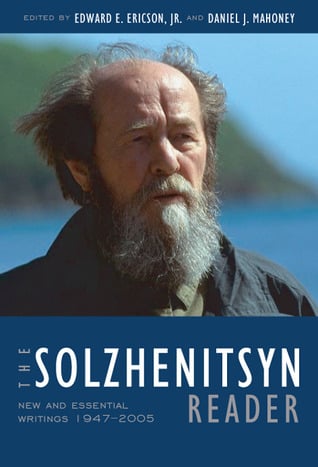

The Solzhenitsyn Reader is edited by Edward E. Ericson, Jr., and Daniel J. Mahoney, two paragons of Solzhenitsyn scholarship. Their Introduction serves as a succinct biography of Solzhenitsyn’s life for those unfamiliar with it and as a brief and astute critical analysis of his thought.

Having established the context in which the works should be seen and read, the editors present us with their selection of what is “new and essential” in Solzhenitsyn’s work, beginning with some poetry from Solzhenitsyn’s early period, which depicts his experience of World War II, the ordeal of prison, the Gulag, and internal exile. In their introduction to “Besed”—the fifth chapter of the epic poem Dorozhen’ka (The Trail or The Way), composed in prison between 1947 and 1952—Ericson and Mahoney make a rare error in their seeming insistence that the narrative of the poem is strictly autobiographical. Although, as a whole, the work should be read as an autobiographical narrative of Solzhenitsyn’s experience and the spiritual awakening that arose from the cruelty and suffering depicted, there are surely times when the principal character, Sergei Nerzhin, is a composite of Solzhenitsyn’s experience, incorporating the deeds of men he had witnessed and the actions of others merely reported to him by a third party. To read the poem otherwise is to deny the poet his artistic license, sacrificing the literary on the altar of the literal. Worse, since Solzhenitsyn cannot be assumed to have done everything that Nerzhin does in the poem, art is sacrificed to erroneous fact. Thankfully, such errors are rare in this volume.

Another shadow passes over this early section of poems: the one of which T.S. Eliot speaks in “The Hollow Men”—the shadow that falls between the potency and the existence. More specifically, it is the shadow that falls between the potency of Solzhenitsyn’s original poems and the existence of the translations. I was struck by this when reading “Acathistus,” a veritable and irrepressible hymn of thanksgiving that evokes Solzhenitsyn’s gratitude for his conversion to Christianity. Even if the translation is masterful, we know that something is missing, something is lost.

It is good to see in the section allotted to Solzhenitsyn’s “Stories” the inclusion of “Matryona’s Home” and “Easter Procession”—the former, a masterfully understated presentation of rustic sanctity; the latter, a gratingly graphic depiction of urban vice and vacuity. The sections devoted to Solzhenitsyn’s novels clearly created a problem for the editors. It would, of course, be unthinkable to exclude the novels from such a volume as this, but their inclusion in fragmentary form is far from ideal. Isolated chapters, published out of context, cannot possibly convey the sweep and swath of the plots’ panoramas, nor the layers in which beauty and meaning are revealed. And yet the crime of vandalism involved in picking these novels apart is a lesser evil than the sin of omission that would have been committed in leaving them out altogether. I do wonder why One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was omitted completely when, as a short novel, it could have been included in its entirety; yet my sympathies are with the editors’ insistence that a suitable place of honor be reserved for such voluminous works as The First Circle and Cancer Ward, even if we have to make do with mere fragments of each.

Almost a hundred pages are dedicated to selections from The Gulag Archipelago, a work that actually lends itself well to this selective text-dipping. The editors’ selection included here is sufficient to give a newcomer to the author’s oeuvre a sense of this monument to the mania of the Soviet form of secular fundamentalism. For the vast bulk of Solzhenitsyn’s readers who do not speak his native tongue, the selection from March 1917 and April 1917—those parts of his epic cycle of novels, The Red Wheel, that have not yet been fully published in English—will be most welcome, as will the excerpts from Two Hundred Years Together, his recent controversial study of the Jews in Russia. It was also heartening to discover parts of Russia in Collapse, another recent work, but a little disappointing to find that space was not found for his earlier work, Rebuilding Russia, much of which retains its sociopolitical relevance not merely for Russia but for the entire world. Yet much of what is definitive of Solzhenitsyn’s intellectual engagement with the modern age is to be found in the lengthy section devoted to his essays and speeches: the open letter to the Soviet Writers’ Union; the Nobel lecture; the call for “self-limitation” in one of the essays published in From Under the Rubble; and the valedictory address to the West delivered at the International Academy of Philosophy in Liechtenstein before the author’s return to Russia. And, of course, there is the indispensable Harvard address, which still serves as a touchstone or litmus test of true conservatism.

Since his repatriation, Solzhenitsyn has returned to poetry, specifically to the writing of prose poems—or miniatures, as the editors prefer to call them. Some of these are sublime and allow us to reach further into the soul of the man. Fittingly, The Solzhenitsyn Reader ends as it began, with poetry. Solzhenitsyn may be as austere as a monk, as stern as a prophet, as astute as a sage, as indefatigable as an athlete, and as mighty as a warrior, but his soul is that of a poet. It is here, in the prosodic depths, that the essential Solzhenitsyn is to be discovered.

[The Solzhenitsyn Reader: New and Essential Writings, 1947-2005, edited by Edward E. Ericson, Jr., and Daniel J. Mahoney (Wilmington, DE: ISI Books) 634 pp., $30.00]

Leave a Reply