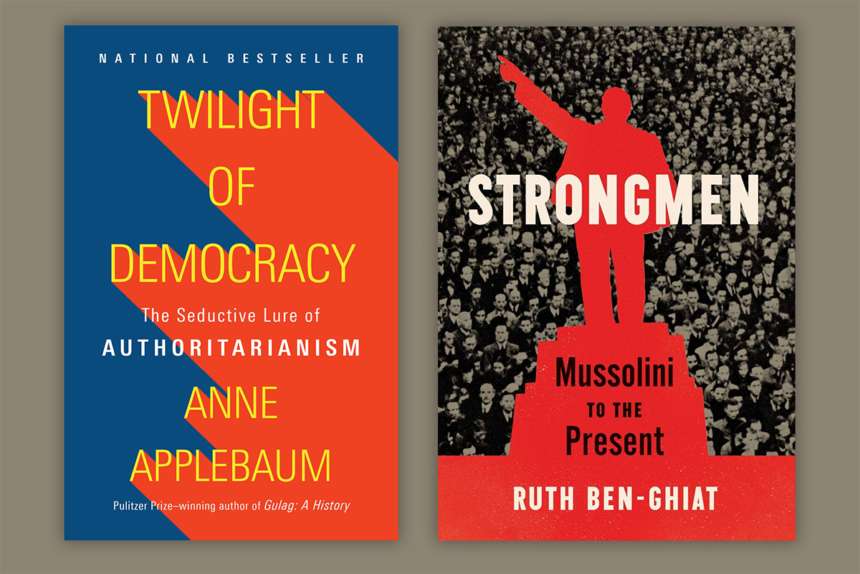

Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism

by Anne Applebaum

Doubleday

224 pp., $25.00

Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present

by Ruth Ben-Ghiat

W. W. Norton & Company

384 pp., $28.95

For some among the chattering classes, the electoral defeat of Donald Trump in November must have been a mixed blessing, though they doubtless could not admit it publicly. After all, the fall of political figures who have been relentlessly and lewdly painted in the press with Hitler makeup for the entirety of their time in office must be enthusiastically and wholly embraced by the morally righteous.

Yet the professorial Chicken Littles who busied themselves during Trump’s presidency producing a whole library of monotonous books announcing the end of democracy in America must certainly be wondering, now that the Queens bogeyman is gone, who will buy the follow-up to their New York Times bestseller enumerating all the ways in which the past four years in America echoed the early 1930s in Germany.

I confess this dismal literature provides me an illicit pleasure. To be sure, good books are the reason readers, and book reviewers, exist. But let us acknowledge that bad books have their place too. For one, they do us the salutary service of teaching us how not to think about a topic. Awful books written by pedigreed intellectuals celebrated among the cultural elite provide us a perhaps even greater good: they can reveal the abject emptiness on which the status claims of those elites are based.

In keeping with the rules for writing apocalyptic prophecies for the Trump-era, Anne Applebaum and Ruth Ben-Ghiat have studiously avoided applying any objective social scientific or historical analysis to the question of what’s happening politically in the West today.

It is indicative of the ideological predispositions of Ben-Ghiat’s book that the anecdote with which she opens, intended to illustrate the most monstrous characteristics of the political strongman, concerns not an episode of egregious political authoritarianism, but rather the prelude to a sexual encounter between a man and a woman. Ben-Ghiat devotes an entire prurient chapter to the strongman’s interest in having sexual relations with women. Virility, she is eager to inform us, is a dangerous thing in political leaders.

As a professor of Italian Studies, she is particularly affascinata by the amorous pursuits of Mussolini and Silvio Berlusconi, but we are of course also treated to banal commentary on the “Access Hollywood” tape from Trump’s 2016 campaign, the porn star Stormy Daniels, and even a tweet in which Trump jokingly pasted his own head on the muscular body of the fictional boxer Rocky. The book’s subtitle might more accurately be rendered “Mussolini to Trump,” as Trump-related topics are the single most numerous entries in the index.

A common academic feminist compulsion is to prattle constantly, in contradiction of all the empirical evidence, about how immersed we are in patriarchal domination, and Ben-Ghiat vigorously asserts that we are now living in an Age of the Strongman. Yet, traditionally assertive masculine figures in politics are less visible now than at any point in history, and women and men who share Ben-Ghiat’s disdain of such masculinity are in positions of political power in many states in the West.

Applebaum’s conceit is not the fatuous feminism of Strongmen, but her argument proceeds from the same subjectivist, emotive logic. She begins with a New Year’s Eve 1999 party at her home, with a group of “free market liberal” intellectual friends, celebrating their cultural power.

Alas, some of those friends have since given in to “the seductive lure of authoritarianism” referenced in her subtitle, and the triumphalist liberal consensus of those heady days is no more. Why and how did it happen? Applebaum has nothing more substantive to offer than the risible psychologizing established in the Frankfurt School of authoritarian studies: her former friends are, for the most part, resentment-filled liars, anti-Semites (she invokes the Dreyfus Affair as a parallel to the present moment), and greedy careerists who realized that, lacking the requisite talents, they would not be able to rise in a meritocracy and have therefore hitched their professional wagons to authoritarian patrons in a tawdry effort to get “rich and famous.”

One supposes she would see it as bad form to ask how much Applebaum has put in her bank account with her polemical writings on this topic, or to note that she, privileged child of a partner in a high-flying international law firm headquartered in Washington D.C., is the very type of person born on third base who somehow thinks she hit a triple. She recounts an exchange with one of her former associates, John O’Sullivan, now a friend to European nationalists, in which he names her “a liberal, judicial, bureaucratic, international elite.” The reader senses that barb broke the skin.

For both Ben-Ghiat and Applebaum, the threat to democracy comes from those who believe nation-states ought to be guided fundamentally by their own interests and by those of their citizens. Just as awful are potent political leaders who doggedly pursue nationalist policies in the face of the vigorous opposition from extra-national and international powers.

There is a gaping leap of logic in this argument. The totalitarian strongman regime originated with Lenin and manifested most frequently in the 20th century in Communist dictatorships in the persons of homicidal lunatics such as Mao, Ceauşescu, Castro, Pol Pot, and the string of supreme leaders of the North Korean police state—yet none of these get more than fleeting mentions by Ben-Ghiat. Lenin would be entirely absent in her book but for a line or two she devotes to his “sparkling intellect.”

An instructive exercise can be performed with the laundry list of characteristics of dangerous strongmen Ben-Ghiat provides. These dictators, we are told, have a savior complex and present themselves as anointed; they opine about the brokenness of normal politics and present themselves as veritable emblems of purity in a sea of corruption; they claim the corrupt media is against them; they hold huge rallies in which they proclaim bombastic rhetoric.

Now, go down this list and plug in a certain Barack Obama. Recall especially his 2008 campaign promise to “fundamentally change America,” the faux Greek columns at his first nomination, and the eight years he spent complaining about Fox News and AM talk radio. Obama checks all of Ben-Ghiat’s boxes. Indeed, has there been a single presidential candidate in recent memory who did not both present himself as the balm to cure division and whine about his media coverage? Haven’t mass events with huge crowds and big patriotic symbols always been the unavoidable stuff of our national political life?

above: Benito Mussolini teases the crowd at Piazza del Duomo in Milan in May, 1930. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09844 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Applebaum knows well the place Marxist revolutionary theory plays in the origin of authoritarianism, yet she is nearly as silent on the face of contemporary left-wing authoritarianism as Ben-Ghiat. Sure, she acknowledges, there are some illiberal leftist states still in power around the globe, but to her the real threat in the West is nationalism. Pay no mind to the American cities burning down under the riotous sieges conducted by Black Lives Matter and Antifa, or the European states facing unprecedented waves of crime and terrorist violence that is the work of radicalized foreign nationals. Also ignore the way mainstream Western politicians on the left, such as the current American president and vice-president, cozy up to left-wing militants.

Neither author attempts to examine empirically the tenets of nationalism, much less to refute them. Applebaum decries a “deep right-wing pessimism about America” but fails to even glance at the reasons typically given by conservative nationalists for their concerns about the future. To wit, marital and familial dissolution; cultural decay under the incessant force of consumerist individualism; immigration-driven demographic transformation with the promise of a permanent and ever-growing electoral majority for the left; elites who have economically sold out the working class for their own bottom lines; the inexorable leftward skew of every single cultural institution. That neither author has anything useful to contribute toward a suitable resolution to our present conflicts may have to do with the simple fact that elite liberal intellectuals like them depend on many of the causes of those conflicts for their status.

The globalist intellectual gentry fancy themselves flying high above the backward populists and nationalists, who, as Ben-Ghiat said with a visible shudder in a C-SPAN interview, don’t even read but only “look at TV.” Applebaum invokes Julien Benda’s La Trahison des Clercs (1927), which describes a culture war between those who have betrayed the scholarly ideal by substituting ideological advocacy for dispassionate analysis, and those who remain steadfastly committed to the academic pursuit of truth. Everything in these two books locates their authors among the traitors to the traditional academic ethic.

The content of these two books does not rise above that of political pamphlets. They denounce their political enemies without understanding or substantively disproving their claims, while boosting an enervated liberalism that neither effectively defends.

Leave a Reply