Like many of his generation, Theodore Roosevelt had a fondness for trekking into wild places and, while taking in the sights, shooting the large game he found. He was especially fond of hunting bears. Doing so, he recounted in Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, heightened his appreciation for his own mortality, and it made him feel pretty good in the bargain. The stuffed Montana grizzly Roosevelt kept in the White House watched over him through frequent rough times, a talisman to remind him of the America he loved, far from the metropolis.

An enterprising manufacturer turned the President’s passion into an icon: the teddy bear, beloved to children for a century now. Never mind the irony; suffice it to say that from target to toy, our bears have been alternately feared and loved, but rarely understood.

Doug Peacock, too, weathered frequent rough times, most of them in Vietnam and its immediate aftermath. He served two tours of duty as a Green Beret medic in the war’s darkest moments, ministering to the Montagnard and Hre peoples of the highlands while trying to dodge the bullets that rang around him. As months of combat went by. Peacock began to lose some of the martial spirit he had brought from his Boy Scout youth. And, as a hunter will, he came to respect his foe, his prey. No longer in a world of gooks and slopes. Peacock describes his dead enemy: “They had been folded up into little fetal-like bundles, just like the prehistoric Indian burials I had found in Michigan as a teenager.”

Wrapped tighter and tighter. Peacock was involuntarily rotated back to the world. On entering his parents’ home, he threw away his uniforms and military papers, saving only his wartime diary, its pages glued together by mildew and fungus. Then he hid himself away until, still malaria-dazed, he headed to Montana. “I had no talent for reentering society,” he writes. “Others of my generation marched and expanded their consciousness; I retreated to the woods and pushed my mind toward sleep with cheap wine.”

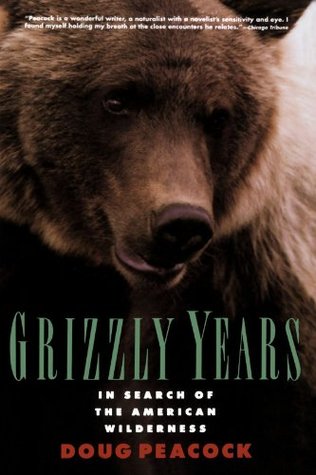

Peacock’s urgent and moving story unfolds in Grizzly Years, with its nicely double-edged title. Its opening page announces all that will follow:

The big bear stopped thirty feet in front of me. I slowly worked my hand into my bag and gradually brought out the Magnum. I peered down the gun barrel into the dull red eyes of the huge grizzly. He gnashed his jaws and lowered his ears. The hair on his hump stood up. We stared at each other for what might have been seconds but felt like hours. I knew once again that I was not going to pull the trigger. My shooting days were over.

In the company of such bears, far removed from the workaday world. Peacock shook off the horrors of his first war. He would not, however, retreat into pacifism, for he found a second war in the continuing encroachment of civilization on the wild lands, in the helicopters, sport hunters, and beef cattle that ranged through once-desolate places. He began to refine techniques of fighting back, performing unauthorized maintenance on yellow construction machines and sporty snowmobiles, terrorizing the countryside with his now-bear-like scowl. His mastery of these dark arts led him to early fame as the model for the hero of the late Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang (1975) and Hayduke Lives! (1990), novels that, like their author and his protagonist, are full of anarchic rage and good humor.

Abbey suggested that Peacock take a proper anarchist’s revenge on society by landing a job with the federal government, and Peacock, now a fire lookout for the Forest Service, took up residence in a tower near Glacier National Monument, close by his beloved bears. There he met his wife Lisa, an adept in the ways of the wilderness, a monkey-wrencher of distinction, and—as is evident in the full-color insert in Grizzly Years—a fine photographer. The two set up house in their ursocentric universe, surrounded by snuffling, rooting, grunting, maundering, lolling, rearing, bawling, and occasionally charging bears.

When fire season ended, the two traveled to Tucson, Arizona, an early Peacock haunt where his friend Abbey lived. There he began to organize research projects on the grizzly bear and agitate for their protection, efforts that were documented in a 1988 PBS documentary called Peacock’s War. For years, too, Doug Peacock labored over the pages of the present book, taking advice from writer friends like Abbey, Peter Matthiessen, and especially Jim Harrison, the poet and novelist.

Their collective efforts are reflected in what is an altogether remarkable memoir. Peacock writes with assurance of his haunted past and occasionally rocky present, never descending into bathos or sentimentality, leading the reader away from both fright and feel-goodism to understanding. Grizzly Years is a genuinely patriotic book. In its pages, the bears of Montana and their world come to life, and through it, we trust, something of the best of wild America will endure and thrive. They have found an eloquent protector.

[Grizzly Years, by Douglas Peacock (New York: Henry Holt) 320 pp., $22.95]

Leave a Reply