Procrastinating readers can pat themselves on the back if they waited to pick up David Rieff’s Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World until it came out in paperback. For one thing, the Los Angeles riots, which so captivated television-transfixed Americans for a couple of days last year until the weekend arrived and the networks had to get back to what they consider to be more important matters, such as the NBA playoffs, rather put to rest any assumptions one might have had about Los Angeles as the great melting pot of the late 20th century. Boiling pot would be a more apt description—a boiling pot of hooligan elements out to have a murderous good time because the “system” as exemplified by trial by jury worked just as it is supposed to work. (Fortunately, David Rieff hurried in an afterward—quite good, in fact—including his own thoughts on the subject.) For another, the storms that pounded the West Coast early this year have probably ended the great seven-year California drought—a pity, in some respects, for Rieff was at his best when imagining ever-booming Southern California trying to boom on with no water.

This said, is there any reason to read in 1993 a writer’s 1990 observations about one of the country’s great, yet also greatly misunderstood, cities? Maybe. But one of the problems with such a study is that, as already mentioned, events have a way of overrunning assumptions. David Rieff’s Los Angeles, increasingly looking outside America’s borders for the people needed to continue fueling a century’s worth of growth and riches, is nearing the point where it resembles not Paradise by the Pacific but the apocalyptic vision of a city-turned-nightmare depicted in the 1982 movie Blade Runner. One could reasonably ask whether Los Angeles had not long ago reached its breaking point and whether what Mr. Rieff was observing (or perhaps discovering) was not a city beginning its process of irreversible decay, but one already well advanced on the downhill slide.

Certainly, the Los Angeles we (my daughter and I) moved to in 1979 was no urban Utopia, and had not been so for some time. Proposition 13, the tax revolt that destroyed the ability of California’s cities, counties, and special taxing districts to provide services as they had always been delivered, was already drying up government coffers. Property, freed from the tax man’s persistent reach, continued to climb in value (though the boom had gotten under way long before Proposition 13), making middle-class housing about the most expensive in the nation. Many whites in the San Fernando Valley had already abandoned the L.A. city schools, not because the schools were filled with immigrant children but because blacks were being bused across the Santa Monica Mountains in a social-engineering project that really was unnecessary (L.A.’s busing program was undertaken as part of a state suit, not through the federal courts) and that California voters quickly outlawed (the proposition prohibiting state-ordered busing was eventually upheld by the California Supreme Court). Traffic, perhaps the common denominator for all Southern Californians, was already intolerable.

During the 1980’s, middle-class Southern Californians did what they have been doing since shortly after World War II—they moved. But whereas the migration out of central L.A, originally went northwest into the San Fernando Valley (most of it annexed early on by the city of Los Angeles), east into the San Gabriel Valley, or southeast into nearby Orange County, by the 1980’s areas available to middle-class people seeking “affordable housing” were located in the desert 50 miles north of L.A., or in Ventura, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties. In reality, the middle-class spread away from Los Angeles was typical of demographic patterns in cities all over America. The only things really remarkable about this out-migration were the numbers of people and the distances involved, and the price those moving were willing to pay to find a little piece of paradise.

But Los Angeles, unlike so many other American cities, also continued to grow, thanks in part to the unprecedented breach of our southern border and to an influx of other nationalities—principally from Asian countries but also from the Middle East and even the then-Soviet Union—taking advantage of relaxed immigration laws. This, too, is not all that remarkable, considering that immigrants are pouring into cities all over the United States and Canada (so many Hong Kong Chinese have found refuge in Vancouver that it is now often referred to as Hongcouver). The fact remains, however, that the sheer number of people filling up areas of traditional Los Angeles such as mid-Wilshire and East Hollywood is enough to convince anyone that L.A. has been overrun by foreigners.

From his vantage point on the city’s tony West Side, Mr. Rieff was apparently awed by this process. The West Side is one of those places where Zoe Baird would live if she got a job on the coast: given enough money, one can live comfortably and largely out of touch with the surrounding riff-raff, even though there seems to be a constant fear that a brown, yellow, or black “invasion” is imminent.

For the great bulk of Southern Californians, the West Side might as well be Fantasyland. Yet—and again, this is the case in any number of cities—the West Side with its lawyers, doctors, politicians, actors, studio execs, and so forth carries a clout disproportionate to its actual numbers. It is, in other words, the place to be in Los Angeles. It is not, however, the most appropriate place to write the book filled with sweeping generalities about a city in transition that Mr. Rieff has attempted. For non- Angelenos, Mr. Rieff’s thesis may seem provocative and forward-thinking. For those who live in Southern California, or for those like us who have lived there and still consider it “home,” it is just one more attempt to explain the unexplainable—the land of remarkable weather and even more remarkable opportunity that attracts even when the downside is so obvious, the cost so prohibitive, the odds so stacked against success.

Los Angeles may now be full of Third World people, but it most assuredly is not a Third World city like Lagos or Calcutta. If immigration is the problem, then it is America’s problem—not just L.A.’s. To attempt to make it otherwise sells short those who continue to see Southern California in an entirely different light—as still the epitome of the American dream.

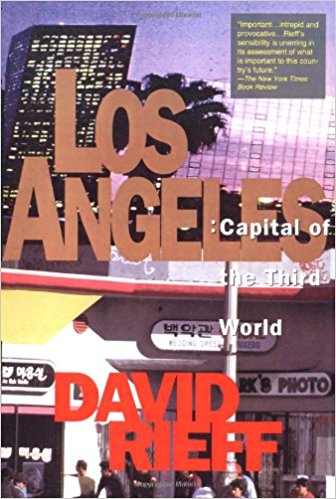

[Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World, by David Rieff (New York: Touchstone) 288 pp., $12.00]

Leave a Reply