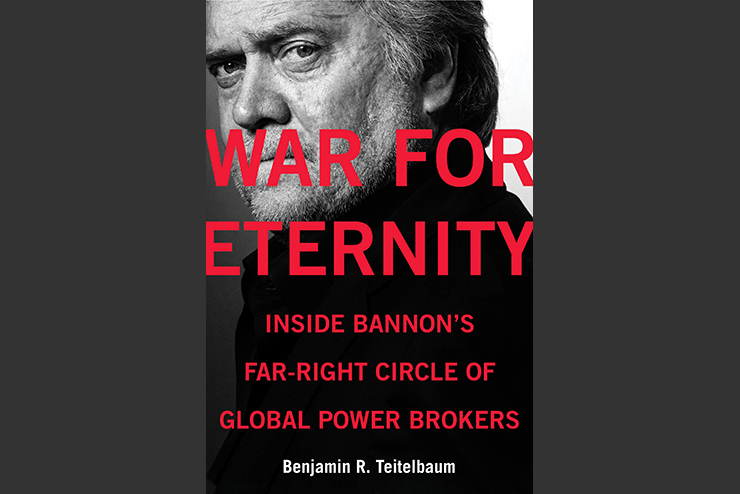

Many intemperate critics have attacked President Trump and his intellectual influences. Benjamin Teitelbaum is not one of them. Cleverer and more fair-minded than most critiques, War for Eternity strives to show that many modern national conservative and populist movements are paradoxically informed by the arcane intellectual current known as traditionalism.

At the book’s heart are 20 hours of probing interviews with Steve Bannon conducted between June 2018 and September 2019. The president’s supposed Svengali is an object of fascination to many, and Teitelbaum’s interest was sparked in 2014 when he heard Bannon alluding to the Italian fascist philosopher Julius Evola (1898-1974). Evola was a central figure in today’s traditionalism, whose writings are circulated almost exclusively on the outermost edges of the right.

When Teitelbaum learned Bannon had an eight-hour private meeting in 2018 with the Kremlin-connected traditionalist Aleksandr Dugin, he became convinced a dangerously outré philosophical movement was galvanizing global politics. At the time, American media were hyperventilating about Russian influence, and Teitelbaum felt “curious and unnerved” to think that “an obscure and exceptionally radical way of thinking had somehow moved from shrouded religious sects and ultraconservative intellectual circles into the White House and beyond.”

Defining traditionalism is the first challenge facing the author. Today’s traditionalism draws heavily on the aforementioned Evola and his French contemporary, René Guénon (1886-1951). But its Western roots have been traced back to Plato, as filtered by early Christian and Renaissance neoplatonists, who formulated what became known as “the perennial philosophy.” This averred there was a single, fundamental, universal, metaphysical truth underlying all religious traditions, and this amorphous idea was absorbed by academics, artists, and religious reformers alike. Romantics embraced it eagerly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, looking ever further back and farther afield for a unifying thread to help them disentangle the age of democracy. With the help of ground-breaking works like Sir James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890), prehistory was plundered to find conceptual commonalities from Greek myth to the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Babylon to Buddhism, Christian apocrypha to animists and Sufists.

But the principal fountainhead was always the “Aryan” lands, where jaded Europeans found an impressively ancient and brilliantly colored cosmology ripe for reinterpretation. They saw in Hindu and Zoroastrian beliefs an exotic antidote to Europe’s technically advanced but spiritually empty civilization—purportedly universal truths and a supposed inexorable order of aristocracy, mysticism, nobility, spirituality, and the warrior spirit. They became convinced there were four repeating “ages” in human history. During the golden age, societies are led by priests, during the silver by soldiers, by merchants during the bronze, and by slaves during the dark age, after which the cycle begins again. Time loses meaning in this reading, as the linearity and progressiveness of both Christian and Enlightenment thought are supplanted by circularity and fatalism. To traditionalists, there is endless decline in human affairs, but there is also endless rebirth—and violent destruction can be creative, because it expedites the endless return.

Traditionalists are frequently eccentric, to put it mildly. Evola believed Aryans descended from ethereal Arctic beings who had coarsened as they migrated south. Viewed from Himalayan intellectual heights, all kinds of mundane preoccupations can seem unimportant, including class, nation, race, religious denomination, and wealth. Even physical reality can seem surmountable, given sufficient discipline.

But these theories can also be influential; permeating conspiratorial, esoteric, and New Age circles, as well as the arts, literature, philosophy, and high society. It is said Prince Charles is a not-so-secret traditionalist. The British composer John Tavener dedicated works to both Guénon and the Swiss-German traditionalist Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998). Such might be expected in rarefied circles. What is less easily understandable is a militant variant of these theories may also be helping propel today’s national populist juggernaut.

Traditionalist concepts and terminology permeate rightist social media, the avatars from Hindu myth oddly analogous to the shape-shifting trolls of the alt-right. From 4Chan to Cambridge Analytica (which Bannon helped set up), minds have been changed, elections swung, and referenda won, using high-tech methodology that may be underpinned by ancient symbology.

The supposedly phlegmatic British voted quixotically to quit the EU, against all “expert” arguments. The ultra-vulgar Trump embraces the believer in aristocracy—at least for a time. Cold-eyed Vladimir Putin has a weakness for the “Eurasian” romancing of Dugin. Jair Bolsonaro became Brazilian President thanks to four seminal texts—the Bible, Brazil’s constitution, a book by Winston Churchill, and Olavo de Carvalho’s 2013 traditionalist manifesto, O mínimo que você precisa saber para não ser um idiota (roughly, The Minimum You Need to Know to Avoid Being an Idiot). Traditionalism-influenced politicians have risen and fallen in France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and elsewhere.

A few rungs down, colorful individuals cluster from Tennessee to Tehran, Virginia to Venezuela. While organizing their political plots, they attend Indian ashrams or Unite the Right rallies, beat drums in forest glades, run small but far-reaching publishing houses and schools (Bannon has been trying to set up his own). State intelligence services are in this soup somewhere, as are Mexican cartels, money from Chinese anti-communists, and agents from Moscow.

Bannon squares theoretical aristocracy with sincere populism because two-party democracy has clearly not benefited working people. To him, the working class is less decadent, and more authentically American, than the modern West’s misrulers. People from any class can become aristocrats because aristocracy is about rootedness and spirituality rather than birth, education, or wealth. “Every person should be a priest,” Bannon reflects, in what may be the book’s most telling sentence. Teitelbaum coins the useful phrase “spiritual mobility”—and the working class might manage this most easily because they have been so long distanced from the intrinsically corrupt centers of educational, financial, media, and political power.

In the shorter term, radical transformative action can best guarantee their economic and existential security. This is akin to the creative destruction beloved of traditionalists, with Trump (or Bolsonaro, or Farage, or Putin) as a necessary “disruptor,” a bullheaded force of nature who throws everything down so that others may build better. Government needs to be slashed, families boosted, globalizing imperialisms (big business, China, equality, “human rights,” Islam, mass migration) restrained, troops brought home, and individuals allowed to find their own levels, all within a spiritually uplifting culture.

Traditionalism, never easily applicable to real-life politics, becomes even less practical when it comes to potential international alliances. While Bannon, Dugin, de Carvalho and others agree on much theoretically—the desirability of a multipolar world, globalism, materialism, rejection of equality, and rationalism—they are rarely able to carry theories through into policy and, in any case, represent cultures with very different histories and geostrategic interests. The principals also have perverse and powerful personalities. When Dugin met de Carvalho, for example, they apparently got into a bad-tempered argument about “sacred geography.”

Clearly, Bannon has been influenced by these meetings and readings, and traditionalism has some bearing on today’s tumults. But in the final analysis, traditionalism is more of an attitude than an ism—let alone a danger to the liberal order. Insofar as it is a discrete ideology, it can as easily be interpreted as an intrinsically universalist creed. Perhaps the publishers sought sensationalism—or maybe, like some traditionalists, the author got slightly swept away by the epic grandeur of his theme.

The truth of the matter may be less aesthetically pleasing—that Bannon read Evola and the others out of sheer intellectual interest, as he once read Madame Blavatsky or Joseph Smith, rather than as an effort to codify some cosmic agenda. He says of himself, “I’m just some f***ing guy, making it up as I go”—a claim some will see as disarming, but others as disingenuous.

Teitelbaum himself sometimes seems uncertain of Bannon, and he is commendably unwilling to rush to a final judgment. While he and we await events, and watch the metapolitical stars, we have for our edification his able and interesting survey of a recondite—and oddly relevant—tradition.

Leave a Reply