The Long Night of the Watchman: Essays by Václav Benda, 1977-1989 (St. Augustine’s Press; 352 pp., $35.00). On July 4, 1983, in Prague, there occurred one of those moments that may rightly be considered a single loose pebble that caused an avalanche. Film director MiloŠ Forman had been permitted to return to his native Czechoslovakia by its then-Communist overlords, to film the movie Amadeus (1984).

On that day one of the opera scenes was filmed in the great Estates Theater, the site of the first performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. In addition to cast and crew, there were about 500 Czech extras in period dress present. When Forman yelled action on the first scene, instead of Mozart’s music, “The Star-Spangled Banner” began to play and an American flag unfurled from the rafters. The cast, crew, and all the extras stood up and began to sing the United States’ national anthem, in English! All, that is, but for the extras who remained sitting, with confused or terrified expressions—the secret police.

In 1977, a disparate group that included ex-Communists, Catholics, Protestants, artists, intellectuals, socialists, and other dissidents banded together to draft Charter 77, a document challenging the reigning polity and to ensure that the government abided by the provisions of the Helsinki Accords, which included a range of civil, political, and economic rights.

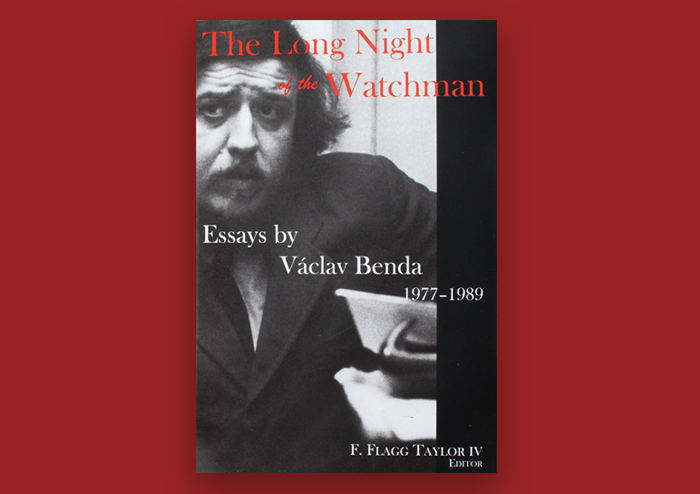

One of the group’s leaders was Václav Benda, a husband, father, and intellectual. Outside of scholars of samizdat and the Cold War, personages such as Benda are relatively unknown in the U.S. Yet their influence among their own people and their heroism in attempting to breathe free air amidst the smog of the worker’s paradise was just as significant as the better-known Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn or Václav Havel. Czechs breaking into song on America’s Independence Day in the middle of communist Prague would not have been possible were it not for Benda and Charter 77.

The Long Night of the Watchman is a collection of Benda’s writings ably edited by F. Flagg Taylor IV. The book is divided into three parts composed of “Reflections,” “Essays and Inquiries,” and “Reports and Defenses.” The strategy of Benda and the chartists was to hold the state to the letter of its own laws so as to create spaces of freedom where culture could develop. While some of Benda’s writings are very technical, written in response to particular circumstances of totalitarian rule, they demonstrate a precision of thought and analysis that embarrassed and outmatched his statist opponents. The book is not so much a gripping read of heroics in defiance of the state, but a record of chess strategy, in which Benda is Garry Kasparov and state officials are checkmated, one by one.

Benda’s thoughts on the preservation of culture, religion, and tradition would have made him at home with the ancient Romans and their reverence for their ancestors, the scholastics of the High Middle Ages in their seeing a coherence in all of reality, and the political realism of his Anglo fellow travelers, Edmund Burke and Russell Kirk, and their insistence on the independence of the family and loyalty to intermediate institutions.

Possibly Benda’s most widely known essay is “The Parallel Polis,” written at a time when dissidents were looking for ways to live outside the totalitarian state. There he outlines timeless principles necessary to build a parallel culture outside the state.

Benda’s subsequent writings and political conservatism estranged him from his fellow chartists after the fall of the Iron Curtain. He explicates this notion of articles of peace between the philosophically disparate—specifically on some socialist elements within this group—in his “Letter to Roger Scruton” written in January 1985:

…I would formulate my position maybe thus: to oppose all Socialist ideas and fabrications untiringly and completely mercilessly; especially to unmask pre-emptively every camouflage which could enable it to rise again from the ashes…However, I would behave as considerately and as tolerantly as possible towards all Socialists (I don’t of course mean henchmen or the guards of the The Gulag), always prepared to meet them more than half-way, and overlook a dozen of their unbearable habits and resentments for the single human moment which would perhaps enable them to recover from that fatal enchantment.

As an ever more explicit left-wing and subjectivist-materialist-relativist-sexual totalitarianism infects the U.S., a thoughtful populace would do well to engage with the writings of Benda. He has much to offer in terms of a defiant detachment from “our betters.” However, this book will probably not interest the casual reader; it is more for the political scientist, those interested in Czech history or the Cold War, or those interested in totalitarian systems and their philosophical underpinnings. For the last, Benda ranks along with thinkers such as Hannah Arendt in his analysis.

In Benda’s view, totalitarianism could not be defeated from within by competing doctrines but only could be undone by organic rebellion: “a single loose pebble can cause an avalanche, an accidental outburst of discontent in a factory, at a football match, in a village pub, is capable of shaking the foundations of the state.”

This volume is also for anyone who wishes to engage in intelligent conversation on the role of the state and the nature of man. In this last sense, I suppose it is for every Chronicles reader.

(John M. DeJak)

Leave a Reply