In 2003, Carlos Eire, the T. Lawrason Riggs Professor of History and Religious Studies at Yale University, published a memoir of his Cuban boyhood, Waiting for Snow in Havana. In a review of this book that appeared in The American Conservative, I suggested comparison with The Last Grove, the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti’s autobiography, or Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis, but concluded that Eire actually surpassed them both, because “he has seen the hand of God somehow hidden beneath the kaleidoscopic wonder” of life. The book deservedly won the National Book Award in the nonfiction category.

Waiting for Snow in Havana ends with Eire, at the age of 11, flying out of Havana as one of 14,000 children airlifted to the United States in the extraordinary Operation Pedro Pan (“Peter Pan”), and thus escaping to freedom. Upon putting down that riveting, magical book, one could not help but wonder, what next? Will there be a sequel? And if there is, will it be up to the first book?

Now there is a sequel, and yes, it is fully the equal of the first book and a masterpiece of American writing. There can be no question that with these two volumes Eire, a superb intellectual historian who has done particularly fine work on such figures as John Calvin and Teresa of Ávila, as well as rediscovered luminaries like Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, S.J. (1595-1658), has established himself as not only an essential chronicler of the depredations of communism but quite simply one of our best prose writers generally. Eire has an hilarious sense of humor and continues to paint unforgettable scenes of boyhood awkwardness or hell-raising that appear to spring from a limitless font of poignant examples. Even more unexpectedly, he is able to weave his memories into a rich tapestry of existential questioning and exploration, hovering on the edge of the abyss or joying in the discovery of new dimensions to reality. Eire’s characters are all real human beings, mythologized into unforgettable archetypes worthy of Dickens.

This is a man who only really started learning English at age 12; one is reminded of Joseph Conrad, or Vladimir Nabokov.

Underlying fine writing of this kind must be a power of memory that is both precise and poetic. Eire presents a cast of tree-characters—large trees lining an avenue in Miami that transform themselves into guardian angels; dreamed-of “Christmas trees” that magically front his new home in Bloomington, Illinois; artist-trees that produce leaves in autumn that are masterpieces of colorful complexity. He writes of boyhood treasures such as Revell model kits; of a cornucopia of candy on his first trick-or-treating experience at Halloween and the “cruel hoax called candy corn” (“Are you sure that this crap counts as a treat?”); and of snow: the snow for which the young Carlos had waited in Havana, the snow that represents “northernness” and the beyond.

Carlos Eire’s perspective on John F. and Robert F. Kennedy, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the Bay of Pigs fiasco (which to him is a betrayal beyond redemption) is unique and essential. The Missile Crisis demonstrates perfectly the dependence of Castro on his Soviet masters, while revealing a certain cluelessness on the part of the Americans. Cubans had not only known about the build-up for some time but had made representations to the C.I.A. that were basically ignored. When the adult Carlos visits Prague, he is able to feel a special empathy for those who had suffered the same plight as his fellow Cubans, while lamenting that the Czechs have been able to escape from oppression, even as Cuba remains under its heel. Carlos’s mother, dubbed “Marie Antoinette” (his father considers himself to be the reincarnation of Louis XVI), having finally emerged from Cuba after a years-long battle with the “Castrolandia” authorities, during a visit to Europe actually comes close enough to Pope John Paul II to shout out in Spanish, “Please, pray for the Cubans!” and is told by the Pope, in perfect Spanish, “I pray for Cuba everyday.” (“Louis XVI” never escapes, but remains behind to guard the family collection of works of art, then dies of a heart attack on the spot when Castro’s men appear at his home to confiscate the entire collection.)

When reading the daily newspaper or watching the television news, I find that I must pinch myself every now and then: Am I dreaming? Did communism never happen? Has one of the world’s worst nightmares vanished into thin air? Such is the power of the news media to construct our pseudoreality! And Cuba in particular seems to occupy a twilight zone of forgetfulness on the part of our journalists and intellectuals in general. Perhaps this is their way of simply avoiding their own obvious error in having idealized Castro. Or is this to give them too much credit? Are they purposefully withholding a true account to punish “right-wingers” for their anticommunism? Eire’s two books weigh heavily in the balance between truth and delusion in this crucially important matter, on the side of truth in historical memory.

One might also see Learning to Die in Miami as one of the great narratives of immigration. We have had a plethora of such books in recent years, most of them dealing with immigrants from parts of the world that have had little or no historical relationship with America: China, Korea, Japan, India. Precisely because the gap they must cross is so wide, they often end in a kind of ironic, self-pitying mood that has little to offer the thoughtful reader. But in this book Eire has given us a story much closer to home. Yes, the alienness of American life to a Cuban boy is fully conveyed. At the same time, the opening of his heart and soul to new experiences is prepared by the fact that there are similarities as well as differences to be discerned, as with some of the south Floridian architecture that is his first experience of the physical American scene, and especially the “Protestant” image of Christ Carlos encounters in Bloomington. It is a warm, welcoming Christ, contrasting dramatically with the bloody, tortured images familiar to the boy from his childhood. But Christ is Christ. The Christian roots, instead of being deracinated, are allowed for the first time to spread. Carlos has found a new life in America, but it is in a way a fulfillment of the old life. Eire quotes Irenaeus of Lyons, Thomas à Kempis, and similar writers to emphasize the boy’s struggle to emerge from the Void. As he does so, he realizes fully what is at stake in emigration-immigration, a just balancing of the old and the new, a willingness to “die” to the old and be born to the new, only to discover that elements of the old have borne fruit in a new way.

There can be no finer “coming of age” account in American literature today. Booth Tarkington’s Penrod and Seventeen come to mind. But Eire stands alone in showing the depth of a boy’s soul; unlike J.D. Salinger’s precocious and terminally cynical antihero, Holden Caulfield, Carlos grasps that hell is not other people, pace Sartre, but emptiness within his own soul. With this he does battle in a manner that rings entirely true. “The Nothingness, the Absence, the utter despair is unbearable. I’m being torn to shreds. I think that I’ll surely die if this feeling doesn’t go away.” But after repeated attacks upon Carlos by the Void, he conquers, with the help especially of The Imitation of Christ. He becomes a true Christian and a true American in an account that deserves to become iconic for our troubled youth.

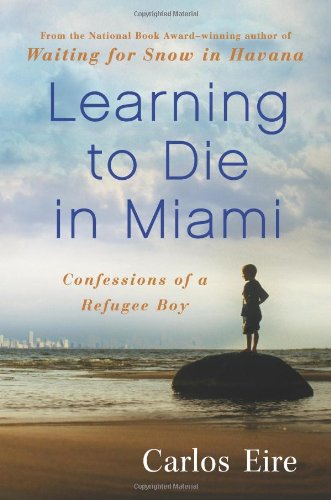

[Learning to Die in Miami: Confessions of a Refugee Boy, by Carlos Eire (New York: The Free Press) 307 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply