Out of the Melting Pot, Into the Fire: Multiculturalism in the World’s Past and America’s Future

by Jens Heycke

Encounter Books

288 pp., $30.99

For years the multiculturalist vision of American identity has dominated our national discourse on matters of race, religion, and ethnicity. Jens Heyke counts himself among those who believe that the multicultural turn, which emerged in the 1970s, was all for the worse. In this work, he argues energetically, if not convincingly, for a revival of the melting pot.

The best that can be said for Heycke’s argument is that his remarks on the dangers of multiculturalism are right on the money. He builds an effective case for the claim that nations which succumb to multicultural arrangements do so at the risk of a variety of “social ills,” among them a lowered standard of living, diminished levels of political freedom, social unrest, and violence—potentially ending in civil war or political collapse.

Heyke defines multiculturalism as a “doctrine that public policies and institutions should recognize and maintain the ethnic boundaries and distinct cultural practices of multiple ethnic groups within a country.” In practice, maintaining such boundaries has usually involved some system of government-mandated preferences “to achieve diversity or to address past injustices or current disparities.” He concedes that the use of the term is a matter of dispute, and that multiculturalism may assume a “soft” form which is really just pluralism—the recognition that disparate groups within a given society should be valued for what they contribute to that society.

Heycke presents a number of chapter-long historical examples, reaching back to the ancient world, of what he terms “fractionalized” or multicultural societies. Among the most interesting of these is the Aztec example. The basic facts are familiar: The conquistador Hernán Cortés sailed for Mexico in 1519 in search of gold and land with a contingent of 500 men and managed somehow to conquer an Aztec force, under the emperor Montezuma, of more than 150,000 seasoned warriors. Historians have attributed this improbable victory to superior armaments, disease, Aztec unfamiliarity with European styles of warfare, and more.

Heycke, relying largely on primary sources, easily disposes of such facile arguments. Instead, he argues, the key to Cortés’s victory was his exploitation of the ethnic divisions within the Empire. As Aztec military dominance had spread to include most of central Mexico, no serious attempt had been made by its leaders to integrate its various cultures, each identifying itself “as separate, maintaining separate temples and gods.” As it began to establish colonies as far south as present-day Guatemala, including subject peoples in 40 different provinces, the Empire attempted to do little more than “exact tribute.” No attempt was made to “integrate the provinces politically or culturally.”

Cortés, to his credit, recognized the underlying weaknesses of this multicultural arrangement and the resentment of many of the subject ethnicities, many of whom were easily persuaded to join the Spaniards in their campaign. Indeed, by the final battle at Tenochtitlan, Spanish forces had been augmented by tens of thousands of renegades who were “Aztec” in name only. “Ultimately,” writes Heycke, “the Aztec Empire fell because there were no Aztecs.” Had Montezuma and his predecessors made any attempt to glue together the empire with, at the very least, a shared language, the Spaniards might have encountered a more formidable resistance.

A more complex example involves the spread of Islam, which began as a kind of successful melting pot, only to decline beginning in the 15th century after the introduction of a multicultural regime known as the millet system.

The expansion of Islam in the first two centuries after Mohammed, and its continuing cohesiveness for centuries thereafter, has sometimes been accredited to the fanatical devotion of its jihadi hordes surging “across the Near East with a Qur’an in one hand and a sword in the other,” Heycke notes. But the most important explanation, he asserts, lies in the Islamic asabiyyah, a term used later by the 15th century Arab political philosopher Ibn Khaldun to describe the cultural unity or shared consciousness that “binds a group together and makes collective action possible.” The common bond that unified the Islamic armies was a deeply felt religious belief.

Most importantly, as the Muslims moved across North Africa and into Southern Europe, they extended their asabiyyah to the conquered—not merely to those willing to convert to Islam but to members of other faiths as well. Conversion of conquered peoples to Islam was the ideal result of this system, but secondarily it was to assimilate non-Muslims, especially Christians and Jews. Toleration was the order of the day and in the Spanish Umayyad caliphate the policy produced an impressive level of cultural and social unification.

However, the Islamic melting pot was gradually replaced by the millet system. The word “millet” derived from an Islamic word for religious denomination, and the millet system was an arrangement in which ethnic or religious millets outside the Muslim faith were reduced to subordinate status, while at the same time granted autonomy to administer their own religious affairs and communal institutions.

The rise of the millet system, however, eventually brought on catastrophic results. One example is the Ottoman Empire, whose millet populations remained largely unassimilated, though unrest and rebellion were mitigated by the practice of allowing some degree of entry into the ruling class through conversion to Islam. “As long as the iron fist of Ottoman power was poised to suppress strife between millets and rebellion against the central government, things held together,” Heycke writes.

And things did hold together until the 19th century, when Ottoman power was tested by territorial rebellions in Greece and in the Balkans. In the case of the former, the genocidal response of the Turks resulted in the murder of hundreds of thousands of Greeks.

Heycke’s quest to find serviceable examples of successful “melting pot” societies in the past leads him inevitably to the Romans, for indeed all roads lead to Rome. He contends that the longevity of the Roman Empire—almost a thousand years if you count the Byzantine centuries in the East—was due largely to romanitas, which Heycke calls the “secret sauce” that nourished Roman political unity. While the Romans never employed the term themselves, it refers to the idea of cultural “Romanness”—the qualities and attributes essential to Roman power and influence.

In explaining romanitas, Heycke reduces it to the willingness of Rome to extend the gift of citizenship to its conquered enemies. As the Emperor Claudius stated in a speech before the Senate: “What proved fatal to Sparta and Athens for their military strength was their segregation of conquered subjects as aliens. Our founder, Romulus … had the wisdom to transform whole enemy peoples into Roman citizens.”

It was only after the rise of Caesar Augustus, however, that this assimilationist view became official policy, helping to replenish the ranks of the Roman legions with manpower from the empire’s far-flung outposts. Indeed, military service was a fast track to citizenship for hundreds of thousands of conquered enemy warriors. They arrived in Rome as slaves but escaped bondage through their willingness to take the oath of loyalty to the emperor and fight beneath the standard of the double-headed eagle.

There’s no doubt that Roman policy was shrewd, and nicely calculated not only to replenish the legions’ ranks but to discourage rebellion by honoring provincial leaders with a status nearly equal to that of their Roman peers. However, while the assimilation of potential enemies may have reduced the threat of rebellion, it did not eliminate it. As students of Roman history know, Roman generals were forever putting down rebellions, as the military career of Julius Caesar illustrates. And while the Western Empire lasted for some 450 years after Augustus’s death, that longevity might be explained just as effectively by a number of factors, including the overwhelming superiority of Roman arms and discipline, not to mention the sheer ruthlessness of the Roman will to power.

Another question has to do with whether the Roman model of ethnic assimilation is fully relevant to modern nation-states, or to the American case in particular. After all, assimilation in the Roman context involved conquered peoples who had little or no choice in the matter. Either they submitted to the Roman model of citizenship, or they remained subjugated or enslaved.

By contrast, assimilation in the American context, with the exception of enslaved Africans, has typically been a matter of immigrants arriving of their own free will under no official compulsion to learn English or to adopt American cultural norms. Few would deny that some degree of cultural assimilation has occurred, but it did so in an organic fashion. To the degree that immigrants who disembarked on our shores assimilated, they did so for practical and economic reasons. When large numbers of non-English speaking immigrants began to arrive in the 19th century from Germany, Italy, China and elsewhere, many preferred to live in enclaves where they might continue to speak their own languages and preserve their own traditions. They did not try to acquire some generic American identity while eagerly throwing overboard their old-world cultural practices, as “melting pot” advocates imagine.

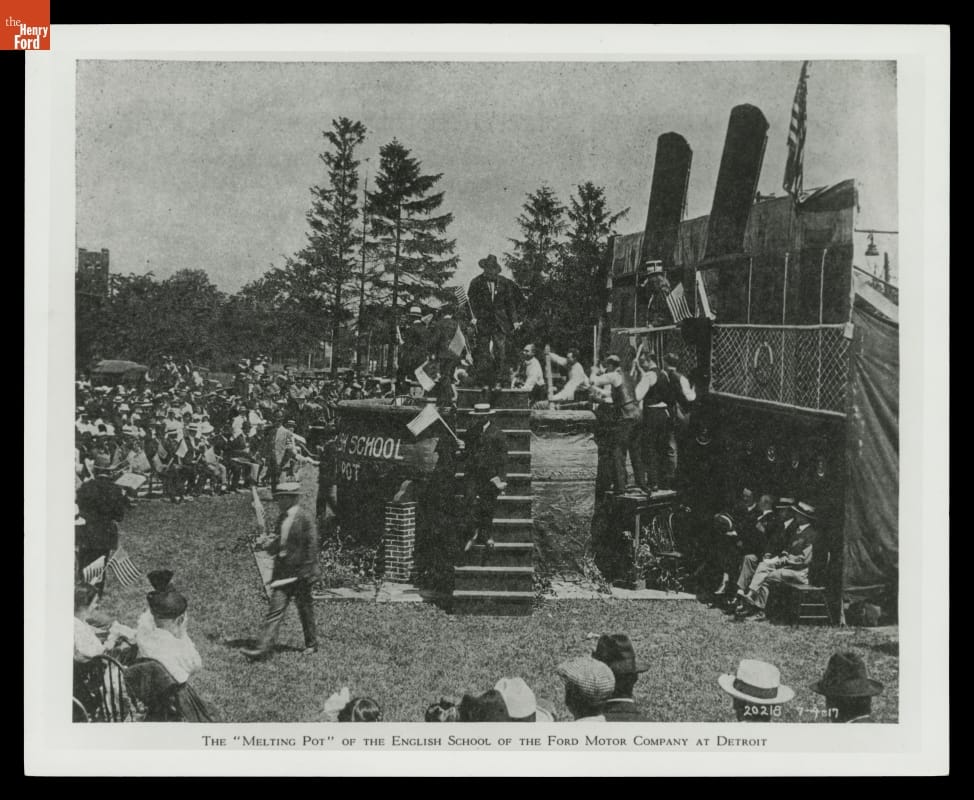

Indeed, they had to be coerced. Henry Ford’s “English School,” which opened in 1914, expressly aimed to convert immigrants in Detroit into thoroughly Americanized drones, ready to work on his assembly lines. Consider this description of one of the English School’s early commencement rituals as reported by historian Jonathan Schwartz:

On the stage was represented an immigrant ship. In front of it was a huge melting pot. Down the gang plank came members of the [graduating class] dressed in their national garbs… Down they poured into the Ford melting pot and disappeared. Then the

teachers began to stir the pot with long ladles. Presently, the pot began to boil over and out came the men dressed in their best American clothes and waving American flags.

Such a ritual seems ludicrous today. Back then it was not far removed from the fantasies of Israel Zangwill, whose 1908 play “The Melting Pot” was fabulously popular for many years. As in the case of Henry Ford, the play inspired many “Americanization” programs in the 20th century’s early decades. Zangwill’s fairy tale endeavored to promote the “new American identity … not based on ethnicity,” as Heycke would have it, “but on a shared love of ideals like freedom.”

(The Henry Ford Museum)

If that doesn’t sound familiar, it should. Heycke has dragged the old neoconservative “universal nation” meme out of history’s dustbin and repurposed it in novel historical garb. The “melting pot” (enhanced with value-added abstractions like freedom and equality) defines who we Americans really are; it is now our romanitas! To hell with our ancestors, our sense of place, our collective historical experience, our shared musical, culinary, and religious heritage. Abstraction trumps history, according to Heycke.

One of the delicious ironies of Heycke’s fable is that the proponents of the Americanization movement were the progressive liberals of their day. Even the suffragettes marched in their ranks! Over a century later, their ideological descendants celebrate a multiculturalism which is little more than the flipside of the melting pot. They invite us to join them at the great American potluck of a thousand foreign cuisines, while they browbeat us in the name of social justice, threatening us with the loss of our livelihoods, transforming our children into self-righteous bullies, and trashing our long-cherished monuments.

To be fair, Heycke does make the useful point that multiculturalists

have simply replaced the old melting pot with a set of new melting pots. These new melting pots don’t just melt people; they trivialize their unique, diverse origins, pigeonholing them into factitious categories that may be useful to political elites, but which reduce their individual identities to a range of skin tones.

But how is the man on Main Street to choose between the melting pot’s tasteless Americanism and the multiculturalists’ Mulligan stew? If he has any common sense left, he would do well to give them both the finger.

Leave a Reply