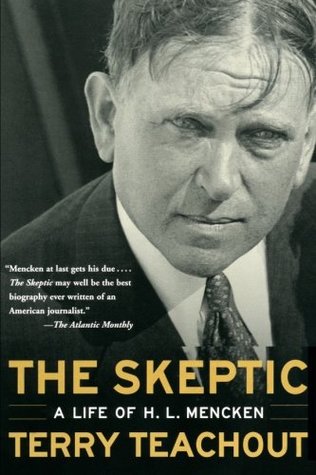

H.L. Mencken has been given a fairly free ride by his various biographers. That ride is now officially over. It might have ended even sooner, had Terry Teachout been able to make up his mind about his subject. For years, Teachout has advertised himself as being “at work” on a biography of Mencken. Now, the reason for the extended birthing process has become painfully clear: Mr. Teachout apparently had trouble deciding what to do with, or to, Mr. Mencken. Alternately attracted to and repelled by his subject, Teachout opted in the end for an exercise in skepticism as a means of reducing his quarry to the ambiguous status of skeptic.

The proof, for starters, seems apparent from the pictures. Having sifted through the visual evidence, Teachout tells us that Mencken’s photographers often captured a man with a puzzled look on his face. For Teachout, that expression was less a pose than an inadvertent self-revelation. Editorial writers are said to be often wrong but never in doubt. Not so the editor of the American Mercury, concludes Teachout, who is certain that the editorial certainty of the Sage of Baltimore was also much more pose than reality. “I doubt even my doubts,” Mencken remarked on occasion. Surely, however, to doubt one’s doubts is to take refuge in a kind of certitude.

Mencken, of course, was a skeptic, especially on the subject of theology. Even here, however, he could not resist playing, at least, with the alternative. Should he ever land in Heaven and there be confronted with his unbelief, Mencken wrote, he would simply look the assembled in the eye and say: “Gentlemen, I was wrong.” At that point, would Mencken have ceased finally to be a skeptic? Probably not.

First and last, Henry Mencken was a cynic. When asked why he continued to live in America, the professional curmudgeon replied, “Why do men go to zoos?” Teachout cannot resist quoting that line. What biographer could? This biographer finds the retort “both funny and memorable” but not “in the end quite good enough.” Why not? Because it points to a “fundamental inadequacy in Mencken’s thought,” namely, a “skepticism so extreme as to issue in philosophical incoherence.” Why not a “cynicism so extreme”?

Teachout compares Mencken unfavorably to Samuel Johnson. Like the redoubtable Dr. Johnson, the formidable Mr. Mencken was “resolutely unsentimental and ebulliently grim,” not to mention driven by an “unswerving commitment to common sense.” While Johnson held out for the “stability of truth,” however, Mencken found nothing that was “wholly good, wholly desirable, wholly true.”

Actually, Mencken did believe, like the ancient Cynics, in virtue and self-control, in independence and self-interest. As he liked to put it: “I believe in being free, acquiring knowledge, and telling the truth.” Whether ultimate truth existed was some-thing else again.

Having invested all these years in H.L. Mencken, the semi-skeptical Teachout finds much to doubt about his subject. He would have us believe that all that remains of Mencken is a cramped sense of “honor,” a concept as “shallow as the Victorian idea of progress in which he believed so firmly (and so paradoxically).” By his own account, Mencken’s “moral code” could be reduced to a single command: “Keep your engagements.” Teachout is not impressed: “No more revealing thing has ever been said about H.L. Mencken.” If Mencken could have read that line, he might have added that it reveals a good deal also about his biographer: namely, a resolutely unsentimental de-termination to deny that there was a Menckenian there there. Here, at any rate, Teachout is surely both wrong about Mencken and forgetful of Mencken’s era. Things may have begun to come apart in the 1920’s, but his was still a time when the rest of the moral code was pervasive enough to be taken for granted (even by Mencken) and strong enough to withstand even its harshest critics (especially Mencken).

Teachout is bent on demonstrating where and why Mencken was supremely wrong about himself. While Mencken bemoaned that he was a man without a country, Teachout finds him to have been thoroughly American in spite of himself and declares his writing a “matchlessly exact expression of the American temper.” While Mencken took pride in being a clearheaded thinker, Teachout judges his philosophy of nihilistic conservatism to be essentially incoherent. Mencken invariably placed himself above the fray, forever the poseur, eternally disengaged. Behind the pose, Teachout finds an engaged man—even, at times, an angry man. Mencken regretted having been born at the wrong time; Teachout has determined that the 20’s and Mencken were a perfect match, given Mencken’s unique brand of social and economic libertarianism. Mencken denied that he was either an idealist or a man of religious faith; Teachout detects Mencken fervently worshiping at the secular altar of scientific progress.

So far, much of Teachout’s analysis is on the money; he is not quite finished, however. Mencken was unashamedly antidemocratic and antifeminist, anti-“booboisie” and anti-New Deal, anti-Hollywood and anti-Bible Belt, among so many other antis derived from his poses, prides, and prejudices. Teachout eliminates none of the above, but adds one of the two ultimate antis of our day—namely, antisemitic—but not necessarily anti-Catholic, even though Mencken did not like “religious Catholics” any more than he liked “religious Protestants” or “religious Jews” and was hostile to, not to mention skeptical of, anyone who claimed to be both a man of intelligence and a man of faith.

On this last score, Teachout squirms and equivocates, hems and haws, but ultimately does for H.L. Mencken what was once done for two men of intelligence and faith, G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. Teachout’s final verdict: “It is not [Mencken’s] anti-Semitism for which he will be remembered—but that he was an anti-Semite cannot now be reasonably denied.” For his part, Mencken did not think that he could “rationally” be called antisemitic. Teachout, however, claims to know better. After all, Mencken thought of the Jews as a people apart (as in the “sharp, unyielding separateness of the Jews”); therefore, he must have been an anti-semite. Moreover, Mencken could be downright nasty in his comments about Jews (and everybody else); therefore, he must have been an anti-semite.

Not content with declaring Mencken to have been wrong about Mencken, Teach-out thinks that Mencken’s admirers have been wrong about him as well—during the 1920’s especially, when his American Mercury was obligatory reading among the educated elite. That elite read Mencken on the Scopes trial and assumed he was one of them. They observed Mencken at war against puritans and prohibitionists and leaped to the erroneous conclusion that he was as liberal and as cosmopolitan as they were. In what passed for the culture wars of the 20’s, those who warred against the “yokels” (to borrow from Mencken) presumed to know instinctively that the Sage of Baltimore was on their side.

But did they know Mencken? The public man may have been the scourge of Middle America, whether rural or urban, but the private Mencken was very much the Victorian traditionalist. In sum, the writer who excoriated the “booboisie” was a member in good standing of the very class of stick-in-the-mud Americans that he so gleefully skewered. He was also a gentleman who paid his bills on time, took his family responsibilities seriously, maintained lifelong friendships (Teachout’s effort to paint him as a serial discarder of those who were no longer useful to him notwithstanding), and was not a nuisance to his neighbors.

On this score, Mencken knew himself very well. Unlike today’s educated elite, Mencken was never in search of anything so ordinary as a sense of place, or anything so laughable as a sense of purpose, or anything so ephemeral as ultimate truth. The first was automatically his by birthright, conveyed by the glories of daily life in the streets of Baltimore. The second was not worth the chase (beyond his disciplined efforts behind his writer’s desk). And the third, for Mencken, did not exist.

Teachout is rightly troubled by Mencken’s worldliness. An agnostic (atheists were simply too arrogant for this arrogant man), Mencken reserved his most searing commentaries for men of belief, especially William Jennings Bryan. To the Sage of Baltimore, the Boy Orator of the Plains was purely and simply a “dolt.” To Terry Teachout, this “dolt” saw something that Mencken could not: that Darwinism was less an expression of immutable truth than an exercise in pernicious ideology. Here, Teachout scores his most telling point. Bryan may have been a country bumpkin, but he was also a man of childlike faith. Mencken may have been a brilliant writer, but he was also a man of childlike faith—and a dangerously misguided one, at that.

There was a time when Mencken was threatened with extinction, a time even before his death when it appeared that he no longer mattered and no longer deserved to be read. During the 30’s, Mencken was so bedeviled by “Roosevelt II” and his infernal New Deal and so unbedeviled by Hitler (“he looked at evil and saw only ignorance”) that he found himself, at best, a thoroughly despised individual and, at worst, a completely ignored writer. That, however, did not last. No man with Mencken’s talent could be kept down for long, much less forever. As World War II engulfed his suddenly ancient world, a sexagenarian Mencken resurrected himself with three delightful volumes of memoirs, and he has remained among the living ever since. True, there was a moment in the late 80’s when the posthumous publication of his private diaries “revealed” that he was a racist, a misogynist, and an anti-semite, after all. Worse still, he stood exposed as a snarlingly insensitive, hopelessly hypochondriacal, damnably penny-pinching clod to boot.

No genuine clod, however, could ever hope to match his inimitable style. And none ever has. Will Teachout’s biography provide one more occasion for temporarily burying Mencken? Teachout, no doubt, hopes not, but his final ambiguous judgment is not designed to convert potential Mencken readers into actual Mencken disciples. For him, H.L. Mencken was “something less than a truly wise man” and “something more than a memorable stylist.”

In sum, Terry Teachout’s biography evokes Mencken’s own estimate of a freshly adjourned session of the Maryland legislature: “It could have been worse.” For Mencken, that was high praise. Indeed, it happened also to be the highest praise he could bestow on a dead cat.

[The Skeptic: A Life of H.L. Mencken, by Terry Teachout (New York: HarperCollins) 432 pp., $29.95]

Leave a Reply