“When people talk of the freedom of writing, speaking, or thinking I cannot choose but laugh.

No such thing ever existed. No such thing now exists; but I hope it will exist. But it must be hundreds of years after you and I shall write and speak no more.”

—John Adams

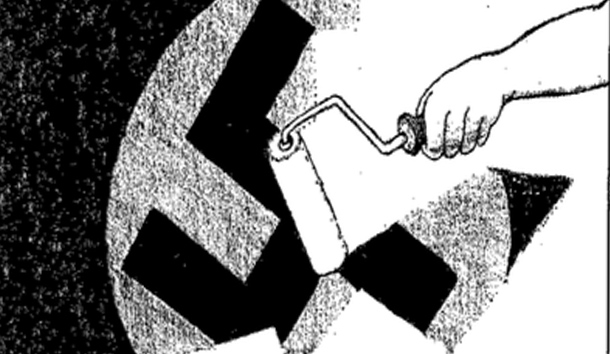

These works highlight the jackbooted political correctness in contemporary European society and document the bitter observation of the German playwright Botho Straus that “the regime of telecommunication represents the least bloody tyranny but the most comprehensive totalitarianism in history.” Klaus J. Groth focuses most explicitly on the tyranny of politically correct opinion. Citing the ravings in the German press against non-leftist scholars and authors, the acts of vandalism unleashed by leftist activists—sometimes in full sight of a passive police force—against conservative publications, and the testimony brought against politically incorrect authors in German courts charged with protecting the post-war constitution against “extremism,” Groth shows German society on the brink of total thought control.

To its credit, the most internationally respected German newspaper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, has resisted the wave of leftist influence. Unlike Die Zeit, Der Spiegel, and Die Tageszeitung, to name just three predictable defenders of German leftist orthodoxy, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung dares to publish critics of the dominant political culture which, according to one of the newspaper’s editorials, now consists of “the politics of arrest warrants, the pillory, and the spirit of police persecution.” According to historian Rainer Zitelmann, who might be speaking about the United States as much as about Germany, “Conservative journalists, intellectuals, and politicians have been excluded [from the political conversation] and thrust into the vicinity of the far Right.”

According to Claus Nordbruch, one can only grasp Germany’s situation fully by looking at its recent history. The postwar German attempt to “overcome the Nazi past,” originally inflicted on a defeated and thoroughly shamed nation by American and British occupying forces, prepared the way for the German embrace of political correctness. Educators and administrators, initially with some prompting, set out to “reeducate” an “anti-democratic” people and to replace an authoritarian German heritage with a denationalized “civic patriotism” (Verfassungspatriotismus).

Nordbruch observes that much of what has promoted leftist thought control in Germany did not always work in this way. Two government agencies now identified with censoring and criminalizing the intellectual right, the Bundesverfassungsgericht and the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährende Schriften, once targeted enemies of bourgeois society. The latter, founded in 1954 as an agency for protecting youth against smut and defending Christian values, now goes after critics of the leftward-drifting political culture. Publications are labeled “dangerous to German youth” if they disapprove of Third World immigration and alternative lifestyles or discourage the expiation of the German right-wing past. Moreover, the Bundesverfassungsgericht, a court that worked to marginalize communist sympathizers, has remade itself ideologically: In the last 20 years, this tribunal has placed under special “constitutional scrutiny” what it describes as a ubiquitous right-wing threat to German democracy. Its reports dwell on the social pathologies, not yet sufficiently addressed by the welfare state, which have resulted in “legions of skinheads” and their intellectual supporters.

Groth and Nordbruch recount horror stories about political officials being forced to resign for not sounding p.c. enough, and highlight the bizarre case of Phil ipp Jenninger, the acting president of the German Bundestag who had to leave his post in 1988 after speaking unacceptably about Nazi treatment of the Jews. On the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, Jenninger made the mistake of not delivering the conventional outpouring of German contrition in the ritualized way. Unlike former Bundespresident Richard von Weizsacker, who repeatedly offered banalities about unconditional German atonement while reminding audiences that “Germany has now the freest state in its history,” Jenninger decided to impersonate in a speech the kind of mindset to which the Nazis had appealed. Though German Jewish leaders praised this performance, Jenninger nonetheless was widely attacked in the press as “insensitively theatrical.” As punishment, he was hounded out of national politics while expressing regrets about his misguided acting. Thereafter, the expression of German national guilt, especially by Christian Democrats, never deviated from the prescribed wooden language.

Nordbruch and Groth are fully aware of the American contribution to this oppressive situation. Both cite American influence on German political culture, and the dustcover of Groth’s book includes the sentence: “Dictatorship has a new name, political correctness, America’s latest attempt to improve the world.” In the 18th century, it was believed that Europe caught cold when France sneezed; now Europe is growing delirious from a specifically American reign of pseudo-virtue.

Ray Honeyford’s study of the English Commission on Racial Equality is both the weakest and the most compelling of these three briefs. Its weaknesses include awkward organization, plodding prose, and desperate attempts to appear moderate. According to Honeyford, until recently England represented the fulfillment of John Locke’s contractual understanding of human society, but the country has been set adrift by the CRE, which has grown in power since its creation in 1976.

The Commission, by now made up largely of nonwhites, has extended its purview to all kinds of cultural and social activities. It has the power to censor a wide variety of publications, oversee the book selection and holdings of public libraries, and inflict penalties on those found guilty of abetting hatred against racial and ethnic minorities. The Commission can force business and educational establishments to engage in costly litigation if its members, on whatever pretext, decide to launch an investigation. Although many of the charges are thrown out of court, the litigation can ruin the plaintiff’s finances and reputation.

While the present Commission has roots in an earlier one established by Parliament in the 1960’s, it also has extended powers granted by the more recent act. The Commission is authorized to censor publications or go after private enterprises on the basis of “hate-inciting effects.” The accused does not have to have incited politically incorrect feelings deliberately: All that must be adduced is the probable effect of a communication or act in order for the CRE to intervene. This assault on English liberty has gone on under Tory, as well as Labour, governments. The Iron Lady clobbered communist-dominated unions but did not take on the more powerful victimological interests embedded in her own government.

Neither Germany nor England has a First Amendment, which occasionally can be successfully invoked to protect the dissenting opinions of those on the right. This does not mean that the politically incorrect in the United States face no professional or social obstacles —nor that they are entirely free of government harassment. But it is still unlikely that 18,000 journalists and educators would be dragged before courts in the United States on charges of “popular incitement” for challenging governmentally established “truths.” When large numbers of German authors were found guilty of “propaganda crimes” and imprisoned, even America’s flagship p.c. newspaper, the New York Times (March 27, 1998), expressed shock at the destruction of German liberty. More German intellectuals are now incarcerated by the German state than under East German communist rule in the I980’s. Nor is it likely that our liberal newspapers would openly applaud the vandalization of ideologically dissident publications. When a conservative nationalist newsmagazine, Junge Freiheit, had its editorial office in Potsdam firebombed, adversarial journalists cheered this act as a preemptive strike on a returning German past.

In my view, the ideological lunacy set loose in Germany is not related necessarily to an ancient German heritage: It is the aftermath of the guilt and opprobrium which Western public opinion has laid upon the German nation. A morally concerned (and among Protestants, obsessively moralizing) people, Germans — even those who try to “contextualize” the holocaust—are preoccupied with the “burden” of the German past. Like its subjects, the government feels itself to be under constant scrutiny and is therefore less concerned about the freedom of Germans than about what the Western liberal press might say about German “rightwing extremism.” Shame as well as guilt drives this repressive politics.

In England, however, the repression is even more striking. A nation without a Nazi past and widely viewed as the cradle of constitutional government, the English are now behaving as insanely as their Teutonic cousins. They have allowed their society to be taken over not only by an expanding managerial state but by the enforcers of multiculturalism. And unlike the Germans who glumly put up with the politics of contrition, the anglophone world, including British Canada and the United States, is into p.c. with a passion. While the stolid German opposition risks imprisonment by tweaking public censors, the English conservative establishment bubbles with enthusiasm for minority outreach and for “moderate” multiculturalism.

Of the English-speaking countries, Canada has by far the worst situation. When the Human Rights Code was introduced in Ontario in 1994, imposing on that hapless province a severe censorship in the name of “human rights,” the response of the conservative and liberal press was predictable. Ontarians were urged to “assist” the government in combating “prejudice” in all forms. Unlike the Germans, English-speaking peoples live in triumphant “democracies” which have won global struggles and are pursuing global missions. In these, one encounters “facilitators” everywhere, even among designated critics. Opposition becomes increasingly inconceivable to the extent that subjects imagine that they rule.

[The Commission for Racial Equality: British Bureaucracy and the Multiethnic Society, by Ray Honeyford (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers) 38pp.,$44.95]

[Die Diktatur der Guten: Political Correctness, by Klaus J. Groth (Munich: FA. Herbig) 320 pp., $33.25]

[Sind Gedanken nock frei? Zensur in Deutschland, by Glaus Nordbruch (Munich: F.A. Herbig) 313 pp., $32.50]

Leave a Reply