Richard Weaver once wrote that it was difficult to perceive the decline of civilization because one of the characteristics of decline was a dulling of the perception of value, and thus of the capacity to judge the comparative worth of times. Weaver, I think, did not have us common folk in mind, for whom it is not at all hard to see when things are getting worse. When the rich flee to guarded enclaves; when the middle class dissolves into the proletariat; when the distinction between citizen and foreigner is lost; when savage criminals go free; when popular culture is reduced to brutal trivialities with no vestige of Christian civilization—then we know that something is wrong.

Weaver’s remarks were addressed rather to the post-World War II intelligentsia who were busy laying out plans for a New World Order. We have grown accustomed to Weaver’s accomplishments and have to be reminded of the heroic context in which they were made—how out of step he was with the glorious dawn of global democracy that formed the stuff of public discourse in the 1940’s. The intelligentsia, after all, spent World War II safely in the United States, gaining in pay, prestige, and power. They did not see the war as the nadir of Western civilization but as a gloriously elating opportunity.

That many of us are able to perceive the moral reality of our times in our materially obsessed culture is due in no small measure to Richard Weaver, the monkish scholar who died at 55, leaving a legacy of eight slim books, half of them published after his death. The scenario of Western decline that Weaver analyzed in Ideas Have Consequences and Visions of Order is confirmed by every day’s news (both its content and its form). He is now accepted as a prophet and one of our keenest social observers. He has attracted considerable attention (nine Ph.D. dissertations so far) and will attract more. Besides the volumes in hand, there are at least three other scholars preparing works on the North Carolinian philosopher.

Mr. Scotchie’s collection, the most valuable contribution to Weaver scholarship so far, should have been published long ago. It gathers 16 previously published (from 1964 to 1992) commentaries on Weaver’s individual works. Weaver as rhetor. Weaver as Southerner, and Weaver’s legacy. Many of the authors will be familiar to readers of Chronicles, including Chilton Williamson, Jr., Allan C. Brownfeld, M.E. Bradford, Marion Montgomery, and Thomas Landess. The many-faceted treatment confirms our sense of Weaver’s enduring importance. (How many celebrated and highly rewarded intellectuals of his time are now utterly and justly forgotten! So it ever has been and is.)

Mr. Young has written a thorough and detailed biography from letters and interviews. He has also elaborated on the background to and influences on each of Weaver’s works, giving them a context that we previously had only in fragments. The influences arc clear—the Southern Agrarians, in particular John Crowe Ransom’s “unorthodox defense of orthodoxy,” and Donald Davidson’s teaching of “language as a covenant.” We learn how Weaver felt about the moral ambiguity of war, and how his deep thinking differed from the gibbering Chicago intellectuals with whom he was thrown.

Out of this heritage and a lifetime of hard study, the reclusive scholar fashioned, as Thomas Landess writes, “a splendid vision of order that no crew of sleek upstarts can ever tear down.”

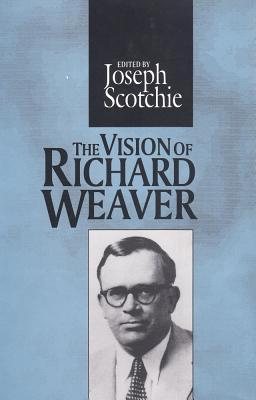

[The Vision of Richard Weaver, Edited by Joseph Scotchie (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers) 245 pp., $39.95]

[Richard M. Weaver, 1910-1963: A Life of the Mind, by Fred Douglas (Young Columbia: University of Missouri Press) 224 pp., $39.95]

Leave a Reply