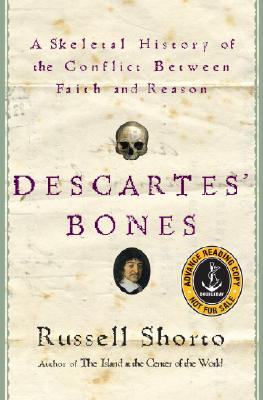

Seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) believed that God moderates reason. That is to say, faith prevents man from falling deeply into error. Yet the writing of this brilliant man of faith—in particular, his Discourse on Method (1637)—has encouraged a separation of faith and reason that has tended to divide human beings from the very God on Whose protection they depend. It has also separated us from our fellow man, and, in a very real sense, created a certain psychological division within ourselves that is characteristic of modern life. Russell Shorto, a writer for the New York Times, realizes that faith and reason are both essential components of healthy human existence. In Descartes’ Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict Between Faith and Reason, he takes on the challenging task of reversing this Cartesian dualism.

The motif that runs throughout the book is that of the relocation of the philosopher’s mortal remains. Shorto uses this peregrination to demonstrate the effect of Descartes’ thoughts throughout the centuries. It is most effective in showing how his famous “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) effectively moved the traditional locus of reality and truth from outside of man (that is, from the transcendent Other), to within man himself. Shorto relates how this new outlook threatened the sacramental system of the Church and reduced the influence of theology, causing the Church to lose Her hegemony over society.

Ample credit is given to the importance of Descartes’ inductive method in laying the foundation of modern scholarship, especially in the areas of medicine, technology, and even political science. But Shorto is aware of the moral alienation that has resulted from the scientific determinism inherent in Descartes’ thinking. It found political expression in the French Revolution; propagated a procession of pseudosciences, including the 19th-century craze for phrenology, which held that the size of a skull and its protuberances could determine intelligence and predict criminality; and provides the basis for the materialist philosophy prevalent today.

Shorto attempts nothing less than the reconnection of man to the metaphysical aspects of his being, relating Descartes’ bones to the idea of relics, usually bone fragments or other objects associated with saints, which help us to keep in touch with those holy men and women who have gone before. Yet the veneration of relics reflects a porous view of reality whereby heaven and earth are in constant communication. Shorto’s adaptation of the practice reflects a very different perspective, one that is essentially earthbound. The “relics” of Descartes speak of a more insular mystery—that of man himself.

While Shorto does believe there is more to man than biology (materiality), this “more” doesn’t seem to have any supernatural source. He promotes Descartes’ view of human emotion as the glue that binds the breach between faith and reason. However, this premise reduces religion to little more than sentimentality. And that is a concept which has been condemned by the Church as modernism, a heresy that rejects supernatural revelation and reduces religion to psychologically induced emotionalism or mere neural activity.

Shorto contends that the mystery of humanity can be unveiled in face-to-face dialogue. (In fact, he sees the human face itself as the revelatory vehicle of both reason and emotion.) Yet, while no one can deny that dialogue is a starting point for insight and healing, personal encounter alone is not sufficient to overcome the differences between the conflicting paradigms of truth that separate the scientific camp from the various traditions of religious faith. Differences in fundamental beliefs are not easily bridged, as the split between Islam and the West, and the divide between pro-life and pro-choice views, readily attest.

The ultimate answers must come from a source that is bigger than either biology or emotion, and is not limited by manufactured intellectual constructs. However, being open to those answers requires a proper understanding of—and belief in—God. And belief requires humility, which is a gift of all true religion and presumes a respect for the dignity of man that comes from a source outside of man.

This book is clever, informative, and insightful, yet it must be read with care. For in the end, Shorto does not unite what Descartes has separated. He merely promotes secular humanism.

[Descartes’ Bones: A Skeletal History of the Conflict Between Faith and Reason, by Russell Shorto (New York: Doubleday) 253 pp., $26.00]

Leave a Reply