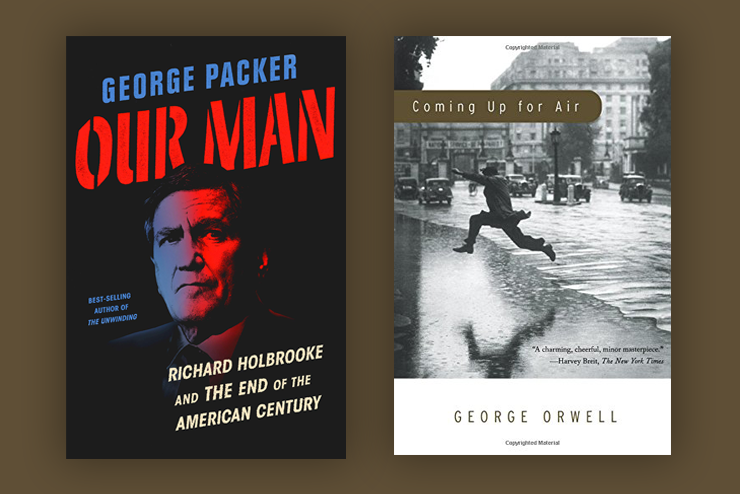

Richard Holbrooke was the most shameless self-promoter in Washington D.C., a town that specialized in self-promotion, as George Packer writes in Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century. He was a social climber par excellence, a sycophant who embarrassed Barack Obama with his flattery to such an extent that he was banned from the Oval Office, and a maniacally hard worker whose heart literally exploded with a ruptured aorta in Hillary Clinton’s office while she was Secretary of State.

Holbrooke was also a slob who would take off his shoes and place his enormous, sweaty feet on one’s desk, and who competed with his son to see who could pass more wind in front of others. He was a Jew who attempted to pass as a Christian until cooler heads prevailed on him that his dissemblance would hurt his career. He was treacherous when it came to women, pleading with the wife of his best friend to run off with him while he was also very much married. He was an absent father whose idea of a perfect evening was one spent with Pamela Harriman, a woman whose closest collaborators admitted “she cared only about money and men who could provide it.”

“Our Man” was probably the most ambitious character I have ever read about, and ambition seen up close is a very ugly thing. Yet, despite being such a monster, Holbrooke saw geopolitical situations clearly as a diplomat in Vietnam and Afghanistan. His caution against intervention was not listened to by either LBJ or Obama. In fact, they did the opposite and upped the price by sending in thousands of more troops, with disastrous results.

Holbrooke’s fans, and they are very few, claim his signing of the Dayton Accords, ending the Balkan wars, was his apotheosis. I disagree wholeheartedly, but that’s what he will be remembered for. What amused me most in Packer’s book were the author’s catty remarks about the personal habits of many people I knew, for example, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. when he was ambassador in Saigon. Packer was born a plebeian and Cabot Lodge a patrician, and it shows in the text. In the same vein, he skewers Holbrooke’s third wife, Kati Marton. But people with very sharp elbows like Holbrooke do not end up with Penelopes, but shrewed Circes.

Still, “Our Man” served his country well and, but for his personal failings, he could not have served it better.

—Taki Theodoracopulos

Seven years before he began writing his post-war masterpiece, 1984, George Orwell published Coming Up for Air, a novel in a different key that presaged the themes of his later book.

Forty-five-year-old George Bowling is a character about as different from Winston Smith as can be imagined. Whereas Smith is sour, wan, and forlorn, Bowling is cheerful, hearty, and optimistic. He’s certain that although the future looks bleak, he’ll remain moderately successful as an insurance salesman. The “streamlined men,” the managerial class running Britain’s show, have created a world of profitable material goods and will soon usher in the next war, less to ward off German aggression than to maintain their privileged position in society. Nevertheless, Bowling’s experience tells him he will weather what’s thrown at him.

Still, Bowling is apprehensive. What chiefly troubles him is the artificiality of life in the 1930s. Having grown up in a farming community as a shopkeeper’s son, he finds the synthetic ingredients used to make foodstuffs especially obnoxious. Reading the label on marmalade, he discovers it’s made with “neutral fruit juices.”

Bowling’s rise to his own questionable estate, he realizes, is through an accident of fate that dislocated him from his proper position in the class hierarchy. During World War I he had been wounded in an air attack, not severely but seriously enough to have been taken out of active duty and put to work overseeing a supply dump in Northern Ireland. There he discovered some discarded books and a lending library. Not having much to do, he spent a year reading what was on offer. He fondly remembers reading H. G. Wells’ The History of Mr. Polly and A Short History of the World. A slender education, but enough to provide him with a skeptical view of the world.

What he learns is that, in the recent past, the world was pretty much the same as the one his ancestors had lived in. This is no longer so. The streamlined men have arrived to obliterate the past in order to create a more profitable and manageable future. They require a more compliant populace who will submit to mass production, mass education, and mass communication. This way, Bowling concludes, lies madness.

Bowling is also not persuaded by Porteous, a retired Oxford-educated public school master who fervently believes there is and never will be anything new under the sun. Porteous believe it’s his professional duty to carry the past into the present.

The novel reaches its climax when a RAF flyer unintentionally drops a bomb on the village of Bowling’s youth. Although apologetic, military authorities are disappointed by the results: only one house destroyed and three people dead. A jar of neutral fruit marmalade rolls out from amid the wreckage accompanied by a stream of blood, symbolizing both Bowling’s fear of the streamlined men and his contempt for the ersatz commodities of modern life.

The merest glance at our contemporary circumstances confirms the prophetic nature of this novel.

—George McCartney

Leave a Reply