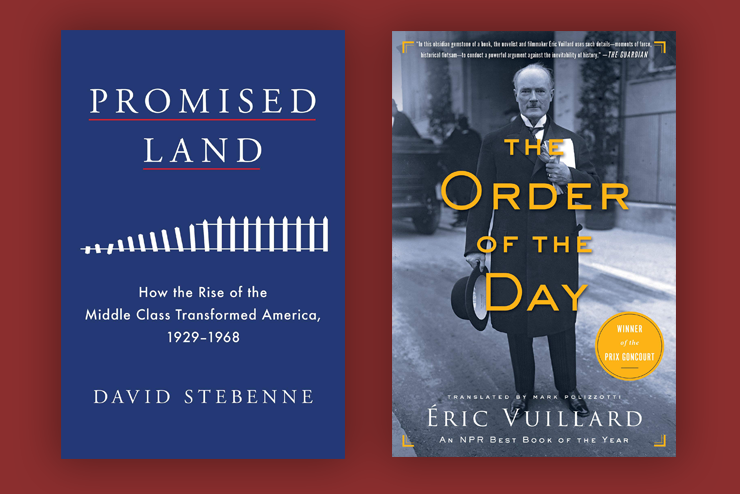

Promised Land: How the Rise of the Middle Class Transformed America , 1929-1968, by David Stebenne (Scribner; 336 pp., $28.00).

Dear David:

I used the title of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly as my grading rubric for your submission on the 20th-century American middle class. Your work recaps the period’s economic, social, cultural, and diplomatic history better than its predecessors. Your concise, clear prose never becomes dull or repetitive. I nodded vigorously in agreement when you concluded, “Being middle class is as much a state of mind as an economic or demographic reality” and when you described Lee Harvey Oswald as “a deranged Marxist.” This was all quite “good” and merited an “A.”

But a closer reading uncovers several weaknesses. While you referenced the period’s best source material, you leaned too heavily on David Kennedy’s Freedom from Fear (1999) and James Patterson’s Grand Expectations (1996). Kennedy and Patterson synthesized cutting-edge monographs to produce award-winning works. Unfortunately, you just synthesized their syntheses, and your book didn’t generate much fresh knowledge about the middle class. And, while I just praised your conclusion, let me add that you should have stated your thesis in the same rigorous manner.

Finally, I understand technological advances challenge methodological practices. But let me make you a promise: I will burn my Ph.D. the minute the professoriate blesses Wikipedia as a historical source. Please delete the numerous Wikipedia citations in your next draft. These considerable shortfalls knocked you down to a “B” as in “bad.”

Now, the ugly. You described, without support, early suburbanites as “racist” and “less open to different kinds of people.” A more generous reading of their flight from crumbling cities would have included personal safety and economic opportunity. Did prejudice drive The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series’ “lack [of] racial and ethnic sensitivity”? Or were their creators just trying to maximize sales to a predominantly white audience? Was Peanuts’ avuncular creator Charles Schulz bigoted? If not, please reconsider how you depict him when, regarding his psychologically complex characters, you note, “All of them at first were white.”

Lastly, we Boomers will never forget Reagan’s ghastly pancake makeup. Who doesn’t know that creepy practice was something “most American men at the time wouldn’t have done”? If today’s hypersensitive readers need that much contextualization…hell, go get the matches. Your political correctness marred your excellent work so here’s a “C” for “C’mon already!” Overall grade: B+

(John Greenville)

The Order of the Day, by Éric Vuillard (Picador; 160 pp., $16.99). This short novel about the preparations for the 1938 Anschluß is closer to history than fiction, and takes the form of a récit (narrative). Through authorial summary and scenic re-creation, it depicts Hitler’s annexation of Austria into Germany as a crucial move to expand his power.

The story begins at a meeting shortly before the March 1933 elections where Hitler solicits contributions from industry leaders at giant companies, some of which are still in existence. The author skillfully depicts the players, including Göring and Hitler, amid a tense atmosphere. Dramatic apprehensiveness abounds, revealed in the nervousness of those summoned, their faces, gestures, and finally their discomfited acquiescence to the extortion.

Similarly dramatized are Lord Halifax’s private meetings in Germany with Göring and Hitler. One cringes at the account. Just as painful is Hitler’s 1938 interview of Austrian chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg. The initially pleasant exchanges turn into humiliating scenes in which the enraged Führer plays, catlike, with the chancellor as with a mouse, before issuing one ultimatum after another. Following his Diktat, Hitler sets the invasion of Austria for March 11.

That very day, Germany’s ambassador to England, Joachim von Ribbentrop, lunches with Chamberlain and Churchill at Downing Street. Enjoying his secret knowledge, he deliberately overstays his welcome. When Chamberlain receives a discreet note informing him that Germany has invaded Austria, he is concerned but loath to interrupt the party.

Vuillard’s book has been showered with awards, including in 2017 the major French literary award for best novel, the Goncourt Prize. The English translation was a National Public Radio “Best Book of the Year.” It attracted notice in the New Yorker and The Wall Street Journal and was short-listed for the 2019 Albertine Prize honoring American readers’ favorite francophone fiction. The Guardian called it, oddly, “an obsidian gemstone.”

Undoubtedly, the novel is well-crafted, but that may not suffice to explain all the press attention and awards. Vuillard, like many French, appears resentful of German bullying. He seems to see in French President Emmanuel Macron a sort of collaborator with the Germans in the abuse of industrial and administrative power. And, even if Vuillard is a patriot of sorts, he appears deeply against nationalism, as well as the capitalism, inherited wealth, and “corporate greed” that he sees in the EU, America, and Brazil. He likes to quote Marxist Antonio Gramsci. Progressive and internationalist critics may have recognized him as one of their own.

(Catharine Savage Brosman)

Leave a Reply