“The earth opened her mouth, and swallowed them up,

and their houses, and all the men that appertained unto Korah, and all their goods.”

—Numbers 16:32

The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 convinced Voltaire (who didn’t need convincing to begin with) of the nonexistence of God. The Great California Earthquake, when it comes (as it must), will only demonstrate the nonexistence of what California has in place of God. Whether it actually manages to convince anyone is another story.

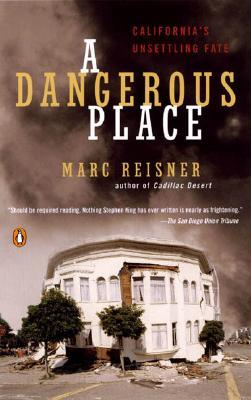

The late Marc Reisner, who died three years ago at the age of 52, wrote what is arguably the best and most important single work on the American West ever published. Cadillac Desert (1987), viewed one-dimensionally, is a history of the development of water policy and water delivery (water “growth”) in the arid Western states, from the Hundredth Meridian to the Pacific Ocean. I am ashamed to say that, when the book first crossed my desk, I gently hefted its formidable bulk and set it aside respectfully as being a volume of no interest to the readers of an East Coast magazine of conservative politics, however worthily it might serve as a doorstop, until, in crippling old age, I found time to read the thing as an act of public duty by an adoptive Westerner. In fact, I got around to the job somewhat sooner than that, after several years of hearing friends refer to the book in piety and at length, like Calvinists citing Scripture. And I discovered them to have been wasted years, like the decades I spent ignoring the music of J.S. Bach. Cadillac Desert is best described as an aqueous version of Centennial by a writer who knew how to write, combining a novelist’s imagination and technique with those of an historian; did his own research; took his time as an artisan in preference to shipping out one prefab monstrosity after another; and had a mind instead of a card-catalogue file above his eyes: James Michener with an intellect, and the literary conscience of a true artist.

As Cadillac Desert was, A Dangerous Place is being described by many reviewers as a work of environmental prophecy. The book is that, certainly; it is not, however, an activist work, Marc Reisner having possessed an unflinchingly realistic mind, not a vulgar one. Unlike most environmentalist productions, Reisner’s work never sought to oppose the People of Light to the People of Darkness, Enlightenment to Greed, Innocent Nature to Depraved Humanity: Though there are villains in his stories, they are human beings, not ideological dolls, treated always with a degree of ironic detachment. Reisner’s California is comparable to Pliny’s Herculaneum and Pompeii, as described by Albert Jay Nock:

The witless agitation of the people—Julia with her necklace, the man with his hoard of gold, the baker leaving his bread in the oven—bore orderly witness to impending disaster due to the fact that the towns should not have been built where they were. So, as viewed by the light of reason, the behavior of Western society in the last two decades is a simple matter of prius dementat, orderly, regular, and to be expected. It presages calamity close at hand, due to the fact that society’s structure is built on a foundation of unsound principles.

In Marc Reisner’s formulation:

Half of San Francisco burned to the ground in 1906. What did we do? We rebuilt and told ourselves it wouldn’t happen again for a long time. Nearly all of Yokohama and a third of Tokyo . . . burned to the ground after the earthquake in 1923. What did Japan do? It put Tokyo right back where it was and made it the most populous city in the world. Another Great Kanto earthquake . . . could become the world’s first trillion-dollar natural disaster. Will the Japanese rebuild Tokyo exactly where it is, after that happens? Of course—I just can’t imagine how, and with whose money. Just as we will rebuild here. Will Los Angeles relocate, now that it’s lost half its water [following Reisner’s imagined Big Quake]? Where?

A Dangerous Place is a posthumously published fragment of an unfinished work. (In the book’s final section, the narrative tenses have not even been made to agree.) For the first 58 pages, the author is back on the subject of water development in Northern and Southern California—with some overlap from Cadillac Desert, though the material remains fresh. For the last 120, he is off on another subject, newer to him and touched on only where necessary in the earlier work: earthquake. “Among civilizations that have overextended themselves, California, rather than settle its human hordes where water is and earthquake zones aren’t, has done the opposite.”

Carey McWilliams, the late author and native Californian who worked for years as editor of the Nation, wrote in California: The Great Exception that “There was never a region so unlikely to become a vast metropolitan area as Southern California. It is . . . manmade, a gigantic improvisation.” By contrast, the development of the greater metropolis of Northern California, known as the Bay Area, was, according to Reisner, “as foreordained as Los Angeles’s was contrived”—despite the fact that, owing to the steepness of the hills surrounding a narrow shoreline, Yerba Buena (the future San Francisco) had nowhere to put all the people who moved there and fresh water only at a considerable distance. What both places shared was the misfortune to be objects of greater-than-serious attraction to a migratory mass of mass men mass-produced by the modern industrial age: rootless by situation, predatory by nature, gullible in mind, and hysterical in temperament. No more than half of California, if so much as that, was ever a paradise. The human locusts arriving in their hordes treated desert waste and fruited Eden alike, fantasizing about the first and exploiting the second as they swarmed destructively over both. The “settlement” of California, north and south, is history’s preeminent example of what inevitably results when postcivilization ambushes pristine nature with the suddenness of a tsunami rolling in upon an unprotected shoreline.

Southern California, centered on Los Angeles, was the deliberate, wildly fraudulent creation of Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler of the Los Angeles Times, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, and the Santa Fe Railroad, working together in what Reisner calls a vast Ponzi scheme to lure an enormous population to the region in the interests of increasing newspaper circulation and realty values and selling Pullman tickets. (Finally, there was Washington, D.C.: “Like almost everything else, aerospace would eventually feed off the federal government—the dynamo behind the city’s post-Depression growth.”) Their scheme worked—far beyond their expectations, perhaps, if not their imaginations. The Bay Area, for its part, was the creation of the first transcontinental railroad, two world wars, the education and scientific-research industries, and the cybernetics revolution. Unlike the development of Southern California,

All of this happened, and is happening, effortlessly. The Bay Area never conspired to grow; it never advertised itself around the world; it had no real need for a chamber of com-merce, Facts and Figures, exhibits at international exhibitions . . . or silkworm booms. It just grew. Unlike Los Angeles, it needn’t have worried a jot about attracting people or industry. Its real problem was where to put them.

What the two regions did and do have in common was a water problem; a seismic problem; and the fact of “the fatal upshot of this state’s century and a half of frantic growth: most of its inhabitants have settled, and will continue to settle, where they shouldn’t have.”

All of these problems were susceptible of solution; and the California immigrants, being, at least as a whole, an ingenious people, discovered them. The trouble is, the solutions they found were temporary in effect and, therefore, in the circumstances, hazardous, and certain to become more so in time, as the state’s population swelled and its infrastructure increased. You didn’t have to be Jack Northrup or Donald Douglas to recognize the fact; and so it is that California ingenuity has been counterbalanced by a stupidity nearly criminal in its deliberateness, to a degree that goes beyond simply confirming the frailty of human nature and the deep inviolability of prideful humanity to the point of showcasing them. To refuse to bear the moral weight of clarity is necessarily culpable. Seldom in history has the discrepancy between technology and wisdom, or technique and morality, been as glaring as it is in the story of California over the last 150 years of its history: perhaps the reason why the rest of the country—in fact, the world—has always tempered its envy of the California way of life with an awed, half-unconscious contempt.

Southern California’s answer to its water problem was to steal what it needed from the farming community in the Owens Valley on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada and transport it 300 miles by aqueduct through the mountains; then to acquire, by deceitful means, more than California’s allotted share of Colorado River water, at the expense of neighboring states, and pump it over a different mountain range and across the desert to the coastal cities. The Bay Area solved its water difficulties by building aqueducts, too, while engineering a system of levees in the Delta region, east of San Francisco and its outlying hills where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers converge in what was originally a wilderness of swamps (part of the Great Central Valley), to create a vast system of sub-sea-level islands where crops irrigated by snow melt from the Sierra Nevada could be raised. (Both Northern and Southern California rely heavily on the Delta as a water source to supply 20 million-plus people.) The Greater Los Angeles region tackled its earthquake problem by ignoring it; the Bay Area faced its own by aggravating the danger—using earth excavated from the steep hillsides as landfill, deposited around the margins of San Francisco Bay on which the city developed further, “laying gargantuan infrastructure atop a migratory landscape.” This fill, in addition to being semisaturated and unstable in the most stable of conditions, is liable to sudden liquefaction in the event of the violent shaking accompanying a major earthquake. According to William Lettis of William Lettis & Associates in San Francisco, “The Bay Area has the highest density of faults per square kilometer of any urban area in the world.”

“For months,” Reisner writes,

I had been wondering which big earthquake, among those considered likeliest to occur, could extract the greatest revenge for all the liberties we Californians have taken with the natural order of the state. If the Hayward fault [running beneath San Francisco] were to produce a quake that wrecks the Delta, the Bay Area would be paralyzed, southern California water-starved [in addition to a great deal else]. . . . What I am about to conjure is not what scientists call the “hypothetical worst case.” My earthquake is a 7.2, high up in the expected Richter-scale range of intensity; most seismologists say a 7.0 is likely, a 7.2 merely possible. It strikes in 2005, which is at the early side of recurrence predictions. Planned re-engineering projects of supreme importance—especially a new eastern section of the Bay Bridge—are not likely to be finished by then.

I am writing now on October 20, 1999. . . . What follows is pessimism that could be worse.

To repeat: Marc Reisner was not an ideologue. For him, as a prophet of California’s destruction (as of the ruination of the West’s ecology by Western water managers and developers), consequences—rather than causes and the burden of responsibility for them—were finally what mattered. In the last 77 pages of his book, Reisner anticipates those consequences, graphically and with narrative power. His scenario is not entirely grim (hundreds, if not thousands, of Berkeley students are crushed to death when the University of California’s antiquated buildings collapse on them), but it is certain to get your attention nonetheless.

And afterward? San Francisco will rebuild itself, Reisner insists.

But billions and billions of dollars will . . . come from American taxpayers living elsewhere, and I can already sense what the rest of the country is thinking: Where does it end? The peninsula segment of the San Andreas fault could produce an earthquake with consequences similar to this. Is it going to wait another century, or is it going to go in . . . 2008? The last Hayward fault earthquake was in 1868. The San Andreas peninsula segment slipped in 1865. Both quakes were nearly as powerful as what we just experienced [imaginatively].

Some environmentalists might have wished to live to see the destruction of California, but Marc Reisner was probably not among them; and so—despite the loss to Western letters his death entails—I’m pleased he didn’t.

[A Dangerous Place: California’s Unsettling Fate, by Marc Reisner (New York: Pantheon Books) 192 pp., $22.00]

Leave a Reply