Rigid conformity and its resultant cancellation of rebels did not begin recently. In English letters, it was practiced nearly a century ago with the blacklisting of a figure who could be described as both a literal and literary swashbuckler. In the 1930s, poet Roy Campbell dared to take on London’s literary Bohemia, the Bloomsbury set, as well as the fashionable, elite, and acceptable opinions of the day. For his clear-sightedness and superb talent, he was shunned, left out of anthologies, and forever condemned to oblivion by the aforementioned elite (or, rather, effete).

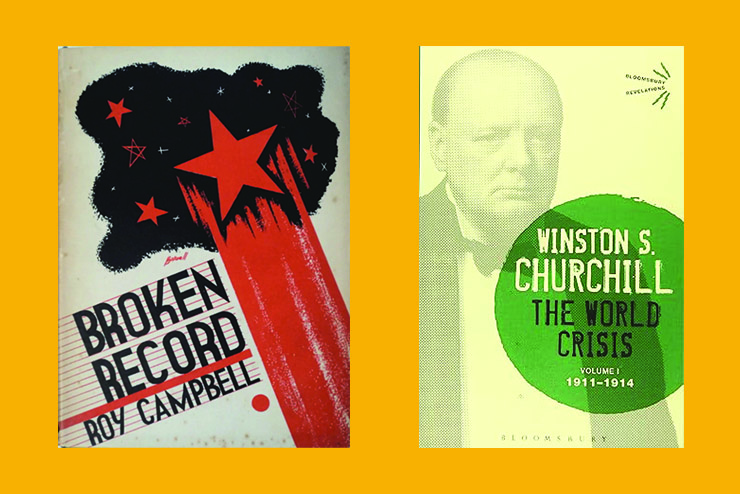

Campbell was a modern poet who saw the obsolescence of being “up-to-date” in morals, manners, literature, and politics. Broken Record, the first of Campbell’s two autobiographies, was published in 1934. As its subtitle suggests, these are “reminiscences” written in a rambling and sometimes disjointed manner. Yet they display keen powers of observation and description.

A portrait of Campbell’s youth in colonial South Africa sets the stage for his adventurous life. Evading a python as a five-year-old, hunting stags, and revelling in the flora and fauna of Africa all contributed to forming his artistic spirit. His adventuring was matched only by his voracious reading. He led a Hemingwayesque life on two continents as a literary man, bullfighter, and equestrian adventurer.

Perhaps bullfighter is be the best general description of this poet. Like most men of tradition, Campbell glimpses eternal verities and communicates with an incisive freshness that transcends time. For the COVID-obsessed, his remark on the epidemic panics of his time: “Anyone who believes in current hygienic voodoo wouldn’t ever dare to take a breath of air.” And, for the haughty literati:

The very priests of culture themselves lead this attack on culture. They have all been bought over, signing an agreement on the side of the Devil to which Faust’s compares as a very slight bargain. The past, with its lessons and warnings, its inherited traditions of human wisdom, its vast reservoirs of imaginative and practical experience, was scrapped in favor of a hypothetical future peopled as yet only by a few inhuman theories.

A return to literary sanity would include Campbell being removed from the modern Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

—John M. DeJak

No rational person can deny that Winston Churchill was a force of nature: soldier, diplomat, historian, government official, world leader, and writer of style and flair. Winner of the 1953 Nobel Prize for Literature, he would eventually write history, memoirs, biographies, even a novel, but many consider his masterpiece to be The World Crisis, a six-volume history of World War I published between 1923 and 1932.

An elegantly written mix of political, military, and diplomatic history and memoir, with striking portraits of other important historical figures, Churchill’s masterwork should be considered the definitive narrative of this conflict, a catastrophe born out of arrogant foolishness, cowardice, paranoia, and intellectual laziness that eventually killed 20 million, injured 20 million more and cost several

European nations large portions of an entire generation.

Churchill begins with a brief flashback to the 1870s to set the scene, briefly sketching out the growing dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, ethnic unrest in the Habsburg Empire and farther to the south on the Balkan peninsula, and the suspicion and antagonism that provoked hatred between various groups. Adding to this was the sloth, stubbornness, and spite in dealing with these increasing tensions until it was too late.

In this largely first-person narrative, Churchill shows the gradual transition of a Europe locked into supposedly foolproof alliances to a continent cut to pieces by ethnic and national antagonisms. Even a century after the fact, it is amazing to read of the partisan government indecision and unfocused leadership in practically every country, and of the disastrous, widespread national misperceptions between nations whose elites should have known better.

Too many national figures were reluctant to face reality, a fact that Churchill ties to the advance of such unrealistic notions as a diplomatic settlement to prevent the war, to a quick and tidy end to the war, and to the use of threats to try to force other nations to back down. When all these tactics failed, war ensued with a reckless brutality that a civilized world never could have imagined a few short years earlier. Trench warfare, submarine battles, the Gallipoli fiasco and the sinking of the Lusitania, and the destruction of entire cities—along with the introduction of tanks, airplanes, and poison gas.

Churchill’s account shows how quickly hostilities spread across the world, to such faraway places as New Guinea and the Bay of Bengal, and how, once begun, halting the carnage proved increasingly difficult.

—Tony Outhwaite

Leave a Reply