“Jesus Christ the same yesterday, today, and forever.”

—Hebrews 13:8

I have never heard of a book about “the historical Moses,” and while philosophers study the thought of Sophocles and Plato, few bother to tell us what the historical Sophocles really said, as distinct from what Plato says he said. Muslims know the historical Mohammed from the Koran and do not ask professors in their Islamic universities to differentiate what sayings Mohammed really said from among the many more that the Koran says he said. But when people speak of “the historical Jesus,” they (using the language of Christianity) imply that the record of Jesus Christ in the Gospels is not a factual, historical account at all, drawing a distinction between the Christ of faith and the Jesus of history. While the quest for the historical Jesus forms a brief chapter in the Christian theology of our times, it is important because it defines how the Gospels are read in the secular academy and even in many Christian seminaries. Annual meetings where scholars debate and vote (using black, gray, pink, and red balls to represent what he certainly didn’t say, probably didn’t say, may have said, and certainly said) are routine; the Holy Spirit is pretty busy nowadays.

The stories of the miracles have challenged faith, but Christians have historically taken it as a mark of grace that they believe. The same data that have impressed scholars during the past two centuries made no profound impression on believers during the 18 prior ones. When historical study promised to distinguish fact from fiction, myth or legend from authentic event, Protestant theologians, mainly in Germany, undertook to write lives of Jesus that did not simply paraphrase the Gospels but stood in judgment of them. An attitude of systematic skepticism raised questions that prior generations scarcely conceived. These considerations engaged theological professors in many universities in Europe and in some American divinity schools and university religious studies departments in particular, with the result that a skeptical reading of the Gospels replaced a believing one. These two books on “the historical Jesus” take for granted two facts: first, that the Jesus Christ of the Gospels, the incarnate God who taught, performed wonders, died on the cross, rose from the dead, and sits at the right hand of God, is not the Jesus who actually lived; and, second, that historians know the difference between them. The Gospels’ Jesus (Meier and Crossan assume) simply cannot pass the test of historical method; the Gospels tell us more than the truth that survives the application of this science. Accordingly, these authors undertake to identify the nuggets of history contained within the Gospel.

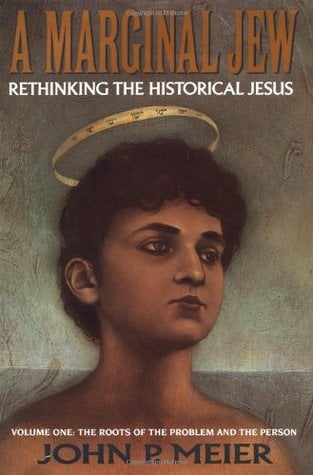

So the Christ of the Church’s faith gives way to “a Mediterranean Jewish peasant,” on the one hand, and “A Marginal Jew,” on the other. These are only two of the many pictures of Jesus that 200 years of critical historical scholarship have painted. The single fact that this “quest for the historical Jesus” has established beyond doubt is that each generation gets the Jesus it wants; pretty much every scholar comes up with a historical Jesus that suits his taste and judgment. The Gospels’ four portraits, intersecting and concentric in many ways, have become legion.

This rigorous, unbelieving historicism actually takes up theological questions. Surely no question bears more profound theological implications for Christians than what the person they believe to be the incarnate God really, actually, truly said and did here on earth. But historical method, which knows nothing of the supernatural and looks upon miracles with unreserved stupefaction, presumes to answer them. The premises of the historical question (did it really happen, did he really say it?) rule out nearly the whole of Christian faith. For they are the routine premises that govern this historical job as they would any other: that any statement we may wish to make about Jesus is just another fact of history, like the fact that George Washington crossed the Delaware on Christmas night, 1776.

But statements (historical or otherwise) about the founders of religions present a truth of a different kind. Such statements not only bear weightier implications, but they appeal to sources distinct from the kind that record what George Washington did on a certain day in 1775. They are based upon revelation, not mere information; they claim, and those who value them believe, that they originate in God’s revelation or inspiration. Asking the Gospels to give historical rather than gospel truth confuses theological truth with historical fact, diminishing them to the measurements of this world, treating Jesus as precisely the opposite of what Christianity has always known Him to be, which is unique.

When we speak of “the historical Jesus,” therefore, we dissect a sacred subject with a secular scalpel, and in the confusion of categories of truth the patient dies on the operating table; the surgeons forget why they made their cut; they remove the heart and neglect to put it back. The statement “One and one are two,” or “The Constitutional Convention met in 1787,” is simply not of the same order as “Moses received the Torah at Sinai” or “Jesus Christ is Son of God.”

What historical evidence can tell us whether someone really rose from the dead, or what God said to the prophet on Sinai? I cannot identify a historical method equal to the work of verifying the claim that God’s Son was born to a virgin girl. And how can historians accustomed to explaining the causes of the Civil War speak of miracles, of men rising from the dead, and of other matters of broad belief? Historians working with miracle stories turn out something that is either paraphrastic of the faith, indifferent to it, or merely silly. In their work we have nothing other than theology masquerading as “critical history.” If I were a Christian, I would ask why the crown of science has now to be placed upon the head of a Jesus reduced to this-worldly dimensions, adding that here is just another crown of thorns. In my own view as a rabbi, I say only that these books are simply and monumentally irrelevant. Premodern Christianity never produced this kind of writing, though it studied the life and teachings of Jesus; Christology was never confused with secular biography until the 19th century. Before then, distinguishing between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith would have produced utter incomprehension.

And yet, Protestant Christianity from the early 19th century and Roman Catholic Christianity since World War II have produced writers who suppose that the Gospels’ Jesus and the actual man are not one and the same person. Instead of interpreting one saying in light of another and the whole in light of tradition or creed or theological premise, scholarship distinguishes, by various criteria, between things Jesus really said and things that the Church, responding to its own concerns, attributed to him later on.

These rules dictate the result of a scholar’s study at the outset of his venture, since by definition they exclude most of what Christians by faith know to be truth: the miracles, the resurrection, the givenness of the Gospels’ message, the (admittedly Catholic) conception that the Bible is the gift of the Church together with that other gift, tradition. But the quest begs the question: Should Christians concern themselves with this particular Jesus at all? And to whom does the life of A Marginal Jew or a Mediterranean Jewish peasant (or a Galilean rabbi, or a homosexual magician, or any and all of the other historical Jesuses that people have produced) matter very much anyhow?

Nonetheless, for those interested not in “the historical Jesus” but in how contemporary scholarship claims to formulate as historical questions what is in fact a theological quest, John P. Meier’s A Marginal Jew is a masterpiece of scholarship. Meier succeeds in bridging the gap between the expert and the lay reader. His is a beautiful piece of writing and research; it is difficult to imagine a finer presentation of the subject. The text is clear and undemanding, the notes superb and enlightening. Meier sets forth the evidence and the issue of method and then tells us what he thinks we can know about the life of Jesus before his public career (volume two will proceed from here).

Meier leads us along the path toward “the Jesus whom we can recover by using the scientific tools of modern historical research.” He offers the following criteria for deciding which words actually came from Jesus: the criteria of embarrassment (the Church was eventually embarrassed by a saying, so it must be authentic), discontinuity (from Judaism), multiple attestation, coherence, and rejection and execution (Jesus did something to alienate powerful people). Meier lists as “dubious criteria” traces of Aramaic, accurate references to the Palestinian environment, vividness of narration, instances of the developing synoptic tradition, and historical presumption.

If you want to know what people think about the historical Jesus, you must start with Meier’s book. But why bother looking for the historical Jesus at all? Meier responds with an essential theological answer: “the quest for the historical Jesus can be very useful if one is asking about faith seeking understanding, i.e., theology, in a contemporary context. . . . faith in Christ today must be able to reflect on itself systematically in a way that will allow an appropriation of the quest for the historical Jesus into theology.”

First, he explains, “the quest for the historical Jesus reminds Christians that faith in Christ is not just a vague existential attitude or a way of being in the world. Christian faith is the affirmation of and adherence to a particular person who said and did particular things in a particular time and place in human history. Second, the quest affirms that the risen Jesus is the same person who lived and died as a Jew . . . a person as truly and fully human . . . as any other human being. Third, the quest for the historical Jesus . . . has tended to emphasize the embarrassing, nonconformist aspects of Jesus Fourth, the historical Jesus subverts not just some ideologies but all ideologies.” And he concludes, “the historical Jesus is a bulwark against the reduction of Christian faith . . . to ‘relevant’ ideology of any stripe. His refusal to be held fast by any given school of thought is what drives theologians onward into new paths; hence the historical Jesus remains a constant stimulus to theological renewal.” Now, with the best will in the world, I find these apologia nothing other than constructive theology garbed as history, theological apologetics claiming the authority of dispassionate scholarship. Why ask history to settle questions that Meier himself specifies as fundamentally religious? And since when do matters of fact have any bearing on the truths of faith? Real historians do not give reasons such as these for writing historical biography. They do not have to.

John Dominic Crossan’s The Historical Jesus gives us a very different book. While Meier concerns himself with issues of method, analysis of sources, and, above all, a broad account of the received scholarly literature, Crossan wishes to present something other than a reference work. He gives us an intensely powerful and poetic book, one by a great writer who is also an original and weighty scholar. Crossan’s Life of Jesus is a pronouncement, not merely an assessment, of the development of an academic discipline. He covers the many categories into which Jesus has been east: visionary and teacher, peasant and protester, magician and prophet, bandit and messiah, rebel and revolutionary. He moves on to John and Jesus, kingdom and wisdom, magic and meal, death and burial, resurrection and authority.

The upshot of this eloquent story is: “That ecstatic vision and social program sought to rebuild a society upward from its grass roots but on principles of religious and economic egalitarianisms, with free healing brought directly to the peasant homes and free sharing of whatever they had in return. The deliberate conjunction of magic and meal, miracle and table, free comparison and open commensality, was a challenge launched not just at Judaism’s strictest purity regulations, or even at the Mediterranean’s patriarchal combination of honor and shame, patronage and clientage, but at civilization’s eternal inclination to draw lines, invoke boundaries, establish hierarchies, and maintain discriminations.” Clearly, we are in the hands of a master preacher, but a historian? I think not. Whoever heard of a historian who ends his book with a sermon, and a political one at that?

Denying a pure and narrow historical motive, Crossan concludes, “This book . . . is a scholarly reconstruction of the historical Jesus. And if one were to accept its formal methods and even their material investments, one could surely offer divergent interpretative conclusions about the reconstructible historical Jesus. But one cannot dismiss it or the search for the historical Jesus as mere reconstruction, as if reconstruction invalidated somehow the entire project. Because there is only reconstruction. For a believing Christian both the life of the word of God and the test of the Word of God are like a graded process of historical reconstruction. . . . If you cannot believe in something produced by reconstruction, you may have nothing left to believe in.” Here Crossan betrays the true nature of his work: history in form, theology in all else—substance, intent, and result.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger makes the point in a variety of important and authoritative papers that, for the Christian faithful, at issue in the identity of the historical Jesus is the Christ of faith. If the question is theological truth, can the answer claim the status of secular fact? Crossan’s somewhat strident concluding sentences imply that it can, and Meier’s characteristically more prudent remarks say as much. Meier and Crossan, both masters of their craft, actually validate Ratzinger’s insistence: let theology be theology, while (for exegetical, not theological purposes) addressing issues of history. No historical work explains itself so disingenuously as does work on the historical Jesus: from beginning, middle, to end, the issue is theological. But how can theological truth about supernatural reality and historical fact concerning this world’s events be expected to meet? For religious faith speaks in the present tense about eternity—how things are and must always be—while historical facts tell us merely what was, once upon a time

[A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, by John P. Meier (New York: Doubleday) 484 pp., $28.00]

[The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, by John Dominic Crossan (San Francisco: Harper) 507 pp., $30.00]

Leave a Reply