Arguing with my liberal high school teachers did not endear me to them. It got worse when a day or two after one of these disagreements I brought to class material demonstrating the teacher had been feeding us a false narrative. The teacher was not doing so intentionally but simply out of ignorance, having accepted a narrative generated by leftists in academe. However, it soon became evident to me that my liberal teachers were quick to accept a leftist narrative not only because it came from university professors, the putative intelligentsia, but because it made America look bad.

The problem only worsened in college. Nonetheless, in those days there still existed a substantial minority of conservative professors. I recall discussing with a conservative history professor a topic of great interest to me. He told me I was right about a particular sequence of events, but then he added, “Remember, it’s not what actually happened that matters—it’s what people believe happened that counts.”

I’m reminded almost daily of what that professor told me. Routinely, I hear falsehoods repeated that are of serious import. Most recently, I’ve heard discussed in various media the reluctance of American blacks to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Now, I can think of a lot of reasons to be reluctant to get one of these new vaccines, but those reasons were not discussed. The reason for black reluctance was said to be that blacks were injected by white doctors with a syphilis-infected serum as part of the U.S. government’s secret “Tuskegee Experiment” in 1932.

This narrative, we are expected to believe, has contributed to widespread distrust of vaccines among blacks. I’ve even heard more than one conservative talk show host say this. It’s what people believe happened. Except it didn’t.

Syphilis was the American Indians’ gift to the white man, and the white man reciprocated with a gift of smallpox. Reciprocity, the basis for all good trade relations! Upon the return of Columbus from the New World in 1493, two Spaniards, historian and physician Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo and physician Ruy Díaz de Isla, reported that members of the expedition were afflicted with a disease unknown in Europe but, according to the sailors, common to the Indians of the island of Hispaniola where Columbus established a small settlement.

It appears that the first European outbreak of syphilis occurred in the seaport of Barcelona in 1493, and then in 1494 in Naples. As the epidemic raged in the Italian seaport, a 25,000-man army of French, Swiss, and German mercenaries, led by French King Charles VIII, came overland to lay claim to the Kingdom of Naples. The city-state was captured easily, but the army returned to France—and some of the mercenary soldiers to Switzerland and Germany—thoroughly infected with syphilis. The French called it the Neapolitan disease, the Neapolitans called it the Spanish disease, and when the disease began to ravage France, the English called it the French disease. And so it went through Europe, seaport by seaport, country by country. What was soon known as the Great Pox struck London by 1496 and Hamburg in 1497.

Initially, it wasn’t understood that the Great Pox was transmitted by sexual intercourse, so no alarm was raised as working girls at the seaports and camp followers of armies on the march continued to service sailors and soldiers. When the connection was made, attempts to prohibit sex outside of marriage became of life and death importance. Brothels were closed. Prostitutes were persecuted.

Dozens of different methods for treating syphilis were devised. All were painful, caused great harm, and did nothing to mitigate the disease. People died by the thousands, including infants. However, as the death toll rose, the most virulent strains of syphilis also died. The effect of syphilis on European populations was typical of a heretofore unknown disease—rapid spread, high death rates, and then sharp decline.

Not until early in the 20th century, more than 400 years after syphilis was introduced into Europe from the Americas, were physicians and scientists beginning to understand the disease, although effective treatment was still 40 years off. One of the reasons for this breakthrough in understanding, if not treatment, was a study conducted in Norway.

Syphilis had been introduced to Norwegian seaports about 1499 but contacts with infected sailors were limited and, although the disease flared for a time, it soon died away. Then, in 1709 a Russian Navy ship seeking shelter for the winter put into port at Stavanger on Norway’s west coast. Evidently, many of the Russian sailors were carrying syphilis, and the disease soon spread not only through Stavanger but also into the Norwegian interior.

Nothing was done to isolate infected Norwegians, and there were as yet no hospitals in Norway which, at the time, was ruled from Denmark and mostly neglected. Syphilis eventually spread throughout Norway and remained a serious health problem for generations, probably because Norway had only very limited exposure to the disease when it first struck Europe.

It was not by accident, then, that the world’s first major study of syphilis was undertaken at the Oslo University Hospital in Norway from 1891 through 1910. The study of 2,000 afflicted patients was overseen by Cæsar Boeck, the hospital’s chief dermatologist, and after his death by two other prominent Norwegian physicians. Every person in the study was monitored and regularly tested but no attempts were made to treat the disease. Boeck and his successors kept detailed records of the natural course of the disease in each of the patients. It’s conveniently forgotten that lily white Norwegians were the subjects of a syphilis study a generation before blacks were subjects of such a study in the U.S.

The U.S. Public Health Service wanted to study syphilis-infected black populations here in America to compare with the syphilitic whites in the Norwegian study. Syphilis rates for blacks in the United States were far higher than those for whites, and blacks seemed to suffer more cardiovascular damage from syphilis than did whites. The Health Service wanted to know if this was a consequence of promiscuity and lifestyle or a difference in biology. It was decided in 1932 to study syphilitic blacks in Macon County, Alabama, where rates of infection, depending on the survey, ranged from 20 percent to 35 percent of the adult black male population.

In conjunction with the Tuskegee Institute, a black college in Macon County founded by Booker T. Washington, some 400 black males afflicted with syphilis were enrolled in the study, which would replicate the Boeck study by following the natural course of the disease without any attempts at treatment. Playing a prominent role in organizing the study were three blacks: the president of the Tuskegee Institute, Robert Moton; the medical director of the Institute’s hospital, Dr. Eugene Dibble; and the chief nurse for the study, Eunice Rivers. All three were strong proponents of the study, thinking that it would be of great benefit for blacks in the Deep South, where syphilis among blacks amounted to a plague.

above: Nurse Eunice Rivers poses for a photograph with two doctors in the Tuskegee syphillis study (National Archives)

The role played by Eunice Rivers was especially important. By the time the study was launched she had been a public health nurse for nine years and knew the rural black community in Macon County particularly well. Black sharecroppers and others had trusted and relied on her for years. She was there for them when, as participants in the study, they had to interact with white doctors from the Public Health Service and with Eugene Dibble and other black doctors from Tuskegee. She made sure the study participants had transportation to and from the Tuskegee hospital, were served meals, and were treated for other medical problems. She was also the one who had the families of those who died sign releases for autopsies in return for funeral benefits.

Nothing about the study was secret. The Public Health service issued its first report on the study’s findings and data in 1934 and continued to issue reports regularly throughout the life of the study. Moreover, schools of medicine and medical journals were quick to use and publish the materials produced by the study. Most of this material is a part of the public record, as are more recent scholarly treatments of the study, available through the National Library of Medicine.

Nonetheless, the manner in which the study was conducted, especially the lack of full disclosure to the patients, later raised questions about medical ethics and caused several doctors to call for the study’s termination, bringing it to an end in 1972.

What seems ethically and morally indefensible to me, though, was that even after penicillin became available in 1947, the physicians at Tuskegee continued the study without attempting to treat their patients with the new antibacterial drug, presumably because they had committed themselves to study but not to intervene in the progress of the disease. By then some of the participants in the study had died—from syphilis or other causes—and others were in the advanced stages of the disease. How much good penicillin would have done them at that point is a question for experts.

But these ethical issues are not what has been mentioned recently. What has been said, emphatically and repeatedly, is that the U.S. government conducted a secret experiment involving the injection of blacks with syphilis-infected serum and then watched the disease progress. That’s the stuff of World War II’s infamous and ghoulish doctors Shirō Ishii in Japan and Josef Mengele in Germany.

The false narrative, though, is what people believe happened, especially American blacks—and that certainly seems to matter more than what actually happened.

Image Credit:

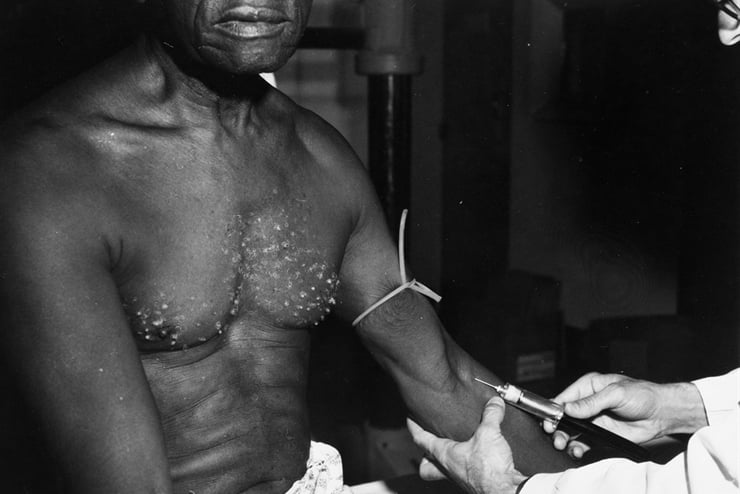

above: a Tuskegee syphilis study doctor with a patient (National Archives)

Leave a Reply