We live—as the choir loudly sings—in a global world; concurrently, the intelligentsia of the West is so degraded, so provincial, and so hopelessly nationalized that globalization seems, on a cultural level, to be best represented by the ubiquitous trash one sees on television. We are now familiar with Japanese pornography, Tex-Mex food, and Korean pop music and dramas, but completely ignorant of the real culture of those seemingly faraway lands, separated by language and misunderstanding. The real culture, one must add, that shows how such cultures feel and think, how they love and hate, and how such feelings have been handed down miraculously through the centuries.

But let us turn first to our own lands. American academics pride themselves on inclusivity, on the faulty notion of scraping the barrel of history for the stories unheard—English programs reek of third-rate, unreadable experimentalism, a rehashed avant-garde whose faults are excused as the scars of, invariably, the immigrant experience, memory, marginalization, interiority, a “lived experience” of oppression, and all the other phrases of politicized literature which have deflated the English language of its majesty.

Excuses are made for the dire state of such works’ quality, but one must nevertheless question the effect of reading them. Have our students become tolerant, elegantly worldly, educated in ways prior generations were not? Of course not, for such a reading is the opposite of true literature’s merit in fostering worldliness: the average, identitarian American reads something understandable to say that they have engaged with something they will never understand. In reality, one reward of literature is to learn upon finishing a truly great work that something that once seemed so distant in time and language and experience mirrors in some essential way our own sense of self. Literature, and painting, and music get to the essence of humanity precisely by our filtering what is ultimately ephemeral and particular—time and place and custom—to capture what is eternal and universal—love and life and death.

Despite their representations to the contrary, it is precisely the intersectional left, and to a similar but less important extent the Old Left, that is most nationalistic, most concerned with values that are first and foremost American, written in English, and marketable to a fashionable conglomerate of readers. Meanwhile, it is precisely the classicists, who nobly defend our learning of Greek and Latin, who seem the most willing to push us outside of our contemporary American microcosm and into the wider world—not simply the globe as it stands, but the globe as it once stood in history.

I must here express my divergence from both groups: I too support the heavy inclusion of non-Western culture in academic curriculums, alongside a return to a rigorous grounding in the classical languages, theology, philosophy, rhetoric, and the languages of German and French. Nothing is more beneficial to a cultivated mind than those thoughts that ever-so-slightly—and thus ever-so-significantly—rethink the thoughts that it already entertains. To read the vast wealth of Persian, Chinese, Arabic, Indian, Japanese, Korean, and other thinkers and writers can only benefit us, as it benefited such worldly scholars of Eastern cultures as Louis Massignon, Arthur Waley, Simon Leys, and countless others who today would be denounced as mere fetishists. How very telling.

But let us turn to that great Other, as they say, which was so great an Other until we realized it was but a mirror of ourselves—let us turn to Russia.

It would not be unwise to note that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s success among Western readers, from Berlin to California, owes something to the demystification achieved by his countrymen’s prior expressions. The figures of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky alone created in the imagination of the Western reader Russian worlds eerily similar to his own. Who of German origin does not see in Dostoyevsky’s gloomy pondering the essence of his own great culture?

Which Frenchman, so consumed by questions of proper love, has not read Tolstoy with electrified fingers upon his pages, desperate to see the next bout of clarity with which he describes the essence of romance? Where scenery and language differed, emotions stood mirrored. And consequently, Western opposition to Soviet excesses could be said to be a residual closeness to the Russians, a closeness engendered, among serious readers, by the graces of those translators who stepped into the infamously arduous realm of apprehending Russian as a non-native. Such a grand parallel does not exist for the nation of China, in spite of its many successful enthusiasts in the West; where most every serious Western reader has engaged with some Russian literature, even the most learned have shied away from the poetry of Li Bai and Du Fu, though their nation and its problems are of prime importance to the American of the 21st century.

Ezra Pound is frequently critiqued by contemporary poets for his appropriation of poetry: his method of translation involved guesswork, amateurish mistakes, and notes penned by the American Japanophile Ernest Fenollosa, whose own understanding of the Chinese and Japanese languages has been heavily questioned. And yet, for all of Pound’s errors, for all that his Chinese poems in The Cantos are not truly Chinese poems, for all that he himself was not as great as Thomas Hardy, Pound nevertheless created a minor sinophilia among American poets, which encouraged young people to learn a language all the more foreboding than Russian. It is this authenticity of engagement so lacking in our present world that fosters negligence, the negligence that does not kill but permits killing to blindly continue.

We must recall that the most outspoken opponents of Parisian Maoism were those enthusiasts not of a present political China, but of the Chinese and their entire history, the sinologists Jacques Pimpaneau, Pierre Ryckmans, Rene Étiemble, Guy Debord, and Claude Roy. Consequently it was those fashionable philosophers and filmmakers—Barthes, Kristeva, Sollers—who knew nothing about China who were so willing to project unto the Cultural Revolution a romanticism reserved only for the French left: the romanticism of idiotic destruction.

It is quite telling that, among such enlightened scholars of French as Alice Kaplan, the politics of the pro-German “collaborators” render virtually all of their work unreadable (one need only look at her article on Céline’s recently published manuscripts in The New York Review of Books), while the death of Jean-Luc Godard, who produced countless films in support of Maoist politics, was mourned by every imbecile across Anglophone Twitter. Perhaps it is our turn to point fingers. Were the noble people who refuse to engage with “fascist” writers more educated on Chinese culture, perhaps they would be just as quick to dismiss those figures who brushed aside the greatest crimes ever committed against the Chinese people. Crimes committed by a regime that, to this day, continues to hold great sway over even America’s universities, films, and culture.

But this would solve nothing: what is good is good, what is not good is not good. What we need to end is the excess of double standards that permits one to dismiss the death of some 50 million Chinese people, while questioning the canonicity of a truly great man for comments he made in a literary bout of polemics.

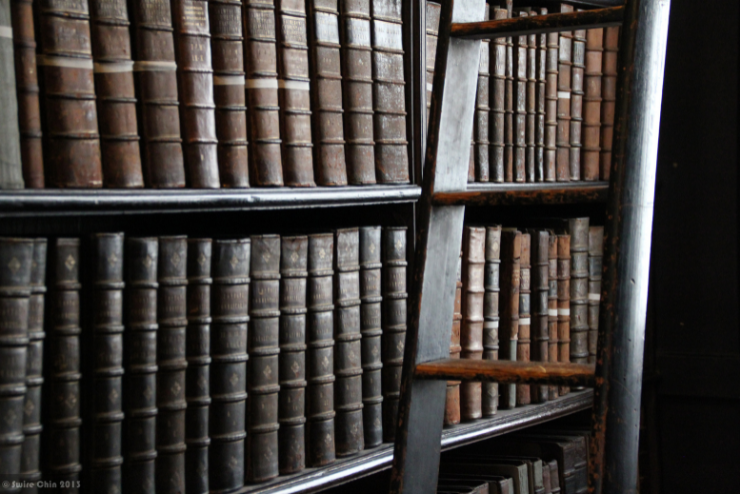

Let us return to the process of apprehension, for it is precisely the process that bridges fantasy and glory. The system of learning languages. One must give the highest palms to men such as Arthur Waley, who learned to read Chinese and Japanese alone while working in the British Museum. Can we picture a modern man capable of learning such languages all by himself, particularly to the level of reading their classics? Yet we have the resources to do such a thing. We may speak freely across the globe, at any hour of the day, with people of any culture we so wish.

Yet such a man as Waley is impossible to imagine today, for we suffer, and consequently our imagination suffers, from the heaviest exhaustion known to man. We have the entire curriculum at our fingertips, without a single semblance of direction. We must here remember that it was Waley’s rendition of Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji (the first novel ever written, though it did not influence such names as Cervantes, Rojas, nor Rabelais) that inspired the American Donald Keene to take up a lifelong career in Japanology, culminating in several landmark translations, and widespread admiration across the Pacific. How splendid the passion ignited by the passion of another, even in the face of something as arduous as learning Japanese.

One can only propose the utility of an expanded curriculum of true diversity in our schools, offering Chinese, Arabic, and Hindi (and thus their entire canons) in place of the saccharine kaleidoscope of American micro-ethnicities which blend together into cultural and ideological conformity. And yet consider the general incompetence of our students in those languages so proximate: French and Spanish. What American child is expected to read in these tongues as his progenitors did some hundred years back? One may propose such an educational ideal while acknowledging that it is faith that animates education, and even our brightest students have no faith left.

The dominant attitude among those who hold the West’s new secular religion is resentment, but among the multitude it is more pernicious: that of ingratitude. It is ingratitude that permits resentment among those educated to know better, and ingratitude that equally prevents the curious from realizing what it is they should like to do with their potential in the first place. Ingratitude permits American youth to neglect the most basic of subjects, to treat education as a mere compilation of checklists within checklists, where information is fed, ephemerally absorbed, and then lost as it is regurgitated back onto the paper.

Intellectual seriousness is so foreign to America’s attitude of ingratitude. We have neglected the utility of demanding rigor from the few brilliant students in favor of placating legions of imbeciles. The apprehension of such languages as Chinese should be mandated as criteria for our elite schools, students, and politicians.

It is not simply a good idea for freethinkers to be knowledgeable of foreign thought in Zhuangzi, Hafez, Confucius, the Koran, and Kalidasa. It is imperative that we shed ourselves of both the Old Left’s fashionable Third Worldism and the New Left’s hobbyistic hyphenations and turn, instead, to Goethe’s ideal of a world literature—and, by extent, a world painting and world music of the most sincere varieties. If we are to live in this global landscape with neither oversensitivity nor fetishization, we must learn again to appreciate deeply what is Other. For how better to answer the left’s call for the cutting up of our Western canon than to place works of a similar weight alongside it?

Leave a Reply