The spectacular rise of the AfD party has alarmed Germany’s political establishment, some of whom are threatening a ban.

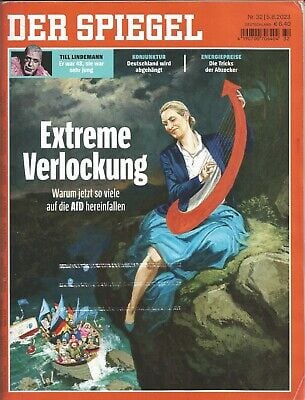

A few months ago, Germany’s leading news magazine, Der Spiegel, ran a bizarre front-page cartoon showing a modern-day “Lorelei” character at the river Rhine with a message underscoring their deep uneasiness about the rise of right-wing politics in Germany. Lorelei, the mythical blond beauty sitting with her harp on a rock at the river, was depicted on the cover in Germany’s leading left-wing magazine with the facial features of Alice Weidel, the co-leader of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

In German mythology, Lorelei lures passing boatmen with her songs. Likewise, in Der Spiegel, one can see far below Weidel’s seat a vessel with dwarf-like Germans wearing hats in the colors of the country’s flag, black, red, and gold, waving at the AfD politician, but unaware that they are drifting dangerously close to the rocks in the river. “Extreme temptation. Why so many Germans are now falling for the AfD,” the headline on the Spiegel cover shouted.

magazine, depicting

Alternative for Germany leader

Alice Weidel as a siren leading

Germans in a boat toward

shipwreck. The headline reads:

“Extreme Temptation. Why so

many Germans are now falling

for the AfD.

The spectacular rise of the right-wing “populist” AfD in the polls this year has alarmed the German political establishment and the predominantly left-liberal media. Within a year, AfD has managed to double their support to more than 20 percent from 10 percent, thus becoming the second-largest party in the polls ahead of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats (SPD) and only about five points behind the Christian Democrats (CDU) and their Bavarian sister party, CSU. Voters’ frustration with Scholz’s three-party “traffic light” coalition (SPD, the Greens, and the Liberals) is running high. AfD’s rise is mainly fueled by voters’ dissatisfaction with high energy prices, costly green climate policies (like a proposed ban on gas boilers), and the out-of-control mass immigration of asylum seekers to Germany, which is again approaching the level of the 2015 migration crisis.

The AfD’s advance has been deeply unsettling for the gatekeepers of respectable opinion in Germany. They call for a firewall against the party to prevent it from gaining legislative and administrative influence. To some critics, this wall resembles the “anti-fascist protection wall” that the former Communist East German regime boasted of creating. When CDU leader Friedrich Merz pointed out that such a firewall is unworkable on the local level in communal assemblies where AfD holds multiple seats, he became the target of attack. Merz quickly returned to the mantra that AfD must never be allowed to be part of any coalition. In the wake of the AfD’s recent surge in the polls, there have even been calls to ban the party.

For decades, the established parties and media had prevented the emergence of any significant political force to the right of the CDU/CSU. They pushed all attempts to form right-leaning challenger parties towards the “extremist” fringe or confined them to a “Nazi” ghetto. This worked well for the left and also the centrist CDU/CSU. However, among the CDU, conservatives were increasingly marginalized and stripped of party responsibilities. This has contributed to the sense that a new party was needed on the democratic right.

The Alternative für Deutschland, founded in 2013, is in many ways the result of mistakes by former Chancellor Angela Merkel and her “there is no alternative” position in agreeing to large bailouts during the Euro crisis. Before that, Merkel had continuously shifted the center-right CDU party to the left (or what she called “to the center”). She managed to steal votes from the SPD and the Greens but increasingly abandoned the right flank, leaving a vacuum there. The CDU had already begun to shift leftwards during the era of Helmut Kohl, but Merkel turbocharged the “modernization,” which in effect was a codeword for the “greening” of the CDU. After the atomic power accident in Fukushima, Japan, she adopted the Green’s opposition to any nuclear power and pursued their costly energy policies.

German conservatives came to despise “Mutti,” as Merkel was called then by many in her party and the German media. Her decision in the summer of 2015 to open Germany’s borders to more than a million asylum immigrants from the Middle East and Africa was the final straw for many conservatives to break from the CDU. AfD entered the Bundestag, the German federal parliament, for the first time in September 2017 with 12.3 percent of the total vote and then had delegates reelected in September 2021 with 10.3 percent.

Against many odds, AfD has broken through that ceiling and is now the second-largest party, according to recent polls. No one expected this level of success when AfD was founded 10 years ago by a small band of dissatisfied conservatives. Junge Freiheit, my newspaper, closely followed the first steps taken by the newcomer party and conducted many interviews with its leaders since then. The emergence of the AfD as a new force on the German right was nothing short of a political miracle. The party managed to grow despite extreme setbacks, including internal organizational chaos, stigmatization by the established political and managerial class, and attacks by Antifa groups.

Since AfD’s leading founders were disgruntled Euroskeptic academic economists, it was dubbed and dismissed as “the professors’ party.” It has undergone several transformations since then. Most of the founders were ousted from their leading positions and have since left AfD. The party is now headed by Alice Weidel, a blonde, intelligent, hard-nosed West-German economist and shrewd tactician (and, by the way, a lesbian mother of two), and Tino Chrupalla a painting company owner from Saxony turned politician. They are now the fourth generation of AfD leaders.

Concerns about the effects of mass immigration, crime, and the fight against the “woke left” have replaced the Euro as the main issue for AfD . The party is especially strong in the east states of Germany, the former GDR, where they have currently gained the support of between a fourth and third of the voters. By attracting protest voters, they contributed to the demise of the left-wing party Die Linke, and to the likely imminent death of the former East German Communist official party SED.

The stunning victory in Sonneberg, a small district in Thuringia, of the first AfD district council administrator with an absolute majority in June has sent shock waves through the German political establishment and the media. That small district vote generated headlines internationally. Even The New York Times and other prominent news outlets sent reporters to the never-heard-of-before Sonneberg district to inquire if a march of the Nazi Brown Shirts was imminent. What they found instead were ordinary people: taxpayers fed up with the established parties, with mass immigration, with the cost-of-living crisis, and with the arrogance of the woke media.

Yet in the words of the liberal establishment media, these Germans have become “more and more radicalized,” “far-right” and even “extreme right.” Grounds for these defamatory allegations are primarily linked to the emergence of Björn Höcke, the regional leader of AfD in Thuringia and a former teacher, whose political friends dominate many of the eastern branches of the party and some in Western Germany. I have made no secret in several published commentaries that I have grave reservations about Höcke, his rhetoric, and his approach. In the worst case, they will lead the AfD to a political dead end.

A strong current of the AfD exhibits open pro-Russia and anti-U.S. leanings. Party leader Tino Chrupalla made an ill-advised visit to the Russian embassy in Berlin on May 9, the Soviet “Day of Victory” (otherwise known as the day of the German defeat in World War II). Some party representatives have come up with crude ideas about breaking up NATO and leaving the bloc, which is quite unrealistic given the sorry state of the German armed forces and the lack of an effective common European defense.

And yet, the polls continue to favor the AfD, despite some of the unrealistic, naïve policy ideas and blunders of its key figures, and despite the relentlessly negative corporate media clamor.

Recently, however, the mainstream pressure against the AfD has reached a high pitch of intensity, just as AfD became more and more successful electorally and in the polls. Some politicians from established parties and some media went so far as to call for a ban on the party. The German Verfassungsschutz, a controversial domestic spy organization charged with protecting the German constitution, has branded parts of the AfD as “extremist” and called it a “suspected case of an organization threatening Germany’s democratic institutions.” (To read more on the history of Verfassungsschutz, see The Peculiar Path in the February 2005 issue of Chronicles.) Verfassungsschutz President Thomas Haldenwang, who must report to the German Minister of the Interior, Nancy Faeser, a Social Democrat politician, has officially declared a third of AfD’s members as “extremists” because they allegedly belong to the wing of the party under the influence of the Höcke. The artillery fire against the AfD is increasing.

“Ban the enemies of our constitution,” thundered Der Spiegel in an editorial. The Hamburg-based magazine is not alone. Saskia Esken, a leader of the SPD, also didn’t exclude the possibility of such a move. Christian Democrat MP Marco Wanderwitz, a failed former government commissar for East Germany who fell out of favor with his Saxon CDU friends, has said that banning the challenger party AfD would give “a breathing pause for democracy.” And, in a Freudian slip, Wanderwitz revealed that desperate politicians are willing to put a pause to democracy when they are challenged and might lose power.

Even German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier (who forgot about his own past as an editor of a radical left journal funded by the Communist regime, which was put under surveillance by the West German Verfassungsschutz) has joined the chorus of howls against the AfD and said that “enemies of the constitution cannot be integrated.”

Meanwhile, Antifa groups in the state of Hesse have published the private addresses of AfD candidates running for the regional parliament and announced that they would “make their lives hell.” There have been numerous examples of AfD members being beaten up, their cars fire-bombed, or their homes attacked with stones or smeared with paint.

As it turns out, all this has not killed the party. The official stigmatization by the Verfassungsschutz surveillance agency, although a burden on the party and a worry for many members concerned about their social reputation and professional positions, especially in the civil service, seems to have become a blunt weapon. However, from my own experience as a founder and editor of a newspaper that was once defamed by a regional branch of the Verfassungsschutz (until the Federal Constitutional Court stopped this attack on the freedom of the press), I can recall that attacks by the Verfassungsschutz can indeed harm one’s operational abilities.

It seems rather unlikely that the federal government, Parliament (Bundestag), or the Federal Assembly (Bundesrat) will dare to ban the AfD by applying to the Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe. Such a process would take years, and legal experts very much doubt that the court would find the case convincing that AfD is trying to destroy Germany’s constitutional democratic order. The accusations rest on dubious arguments that calling for a stop to asylum immigration or deploring a change in the ethnic composition of the population due to mass migration constitutes a violation of human rights. Constitutional lawyers do not agree that the evidence against AfD is sufficient for a ban; most likely, the attempt would fail. And during the process, the party would benefit from a role as a persecuted victim of established parties trying to outlaw a major opposition force.

The respected constitutional law expert Volker Boehme-Neßler believes that SPD leader Esken’s call for an AfD ban has no chance of success. Such a discussion is politically unwise and a sign of desperation. One cannot simply ban a party that has 20 percent to 30 percent public approval ratings, simply because it does not please the left. It would indeed be an attack on the democratic opposition by those who hypocritically pose as the defenders of democracy.

The cordon sanitaire against right-wing parties has mostly collapsed across Europe. The right is now simply too strong to be permanently excluded from sharing power.

Furthermore, the rise of AfD cannot be seen as an isolated phenomenon but points to the broader advance of national conservative and “populist” parties in many European countries. A recent survey by Politico revealed that right-wing parties might gain 23.5 percent of the votes in the next election of the European Parliament. If they were to combine (which is presently unlikely), the two main right-wing groups in the parliament in Brussel (ECR and ID) plus Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party would be stronger than the centrist European Peoples Party of Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (CDU). That would represent a massive challenge for the Brussels establishment and the Eurocrats.

All across Europe, the right is on the move. In Italy, Sweden, and Finland, right-wing governments, which include parties similar to AfD, have come to power recently. Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is a friend of Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. In Spain, the Popular Party came close to forming a national coalition with Vox, which stands further to the right. In Austria, the Freedom Party FPÖ, which has cultivated close ties with AfD, is part of three regional coalitions and polling so strong that they might lead the next federal government coalition. France’s Marine Le Pen is now the most popular politician in her country and stands a chance of winning the next presidential election.

The cordon sanitaire against right-wing parties has mostly collapsed across Europe. The right is now simply too strong to be permanently excluded from sharing power. It remains to be seen if a similar process wears down the firewall in Germany, too. In the present configuration, the big loser is the CDU, which remains captive to the green/left media while scorning any cooperation with AfD.

Leave a Reply