In may of last year, C. Bradley Thompson published a piece in The American Mind entitled “The Rise and Fall of the Pajama-Boy Nietzscheans,” taking aim at the radical left and its cheerleaders at The New York Times, as well as the unfashionably reactionary right. Both, he argues, are fundamentally at odds with the political principles undergirding America’s founding. During the Trump era, the dissident right, in particular, has forced establishment conservatism not only to shift its stances on issues such as immigration and foreign policy, but to raise questions about idols such as universal equality, individualism, and unbridled capitalism.

For Thompson, there is no need to address the arguments of the “anti-American” dissident right; its members must be simply branded as virulent authoritarians and shunned. The principles of the Founders, he argues, are beyond question. They are simply true—“objectively, absolutely, permanently, and universally true.” The historical struggle for truth, it seems, ended happily in 1776. In making this assumption, Thompson reveals the extent to which he and his conservative brand remain in thrall to Enlightenment doctrines that are far from universal, despite claims to the contrary.

According to Thompson, the reactionary right is divided into two camps. The first has a more polished, academic veneer and consists of thinkers such as Iranian-American Catholic Sohrab Ahmari and the University of Notre Dame’s Patrick Deneen. Whether or not Ahmari or Deneen can be accurately characterized as reactionary or consistently anti-liberal (in the Jaffaite sense) is an open question. What is clear is that both thinkers have argued that the liberalism of the Founders was a fragile and flawed concept, one that inevitably transformed into the degenerate progressive liberalism that pervades America today.

Thompson categorically rejects such thinking. In his view, contemporary liberalism is diametrically opposed to the thinking of the Founders, and amounts to a perverse refusal to embrace the high ideals for which the Founders stood—at least if we understand their thought retrospectively through a Lincolnian lens.

In fact, while we need not agree with Deneen and Ahmari that our own debased liberalism is an inevitable outcome of the Enlightenment principles of the Founders, we might concede that Lockean notions of individualism leave little room for the pursuit of the “common good.” But Thompson, sounding suspiciously Nietzschean, will have none of this. He asserts that the common good is merely a recipe for a nanny state which would impose upon us all an overweening, authoritarian social control.

Thompson reserves a special derision for the second group of reactionaries on the dissident right. These “Pajama Boy Nietzscheans” include software developer and neo-reactionary blogger Curtis Yarvin (aka Mencius Moldbug); the mysterious neo-pagan body builder and author of Bronze Age Mindset (2018), known as Bronze Age Pervert; and Daniel DeCarlo, who has written for the Christian blog Mere Orthodoxy.

Thompson’s contempt for this group of thinkers and their works is palpable. The professor, from his catbird seat at the Clemson Institute for the Study of Capitalism, derides the three as “two-bit imposters” and “kiddie reactionaries” who write from “their parents’ basement apartments.” For those who haven’t been paying attention, this is a stale and demeaning cliché frequently employed by members of Conservative Inc.

The so-called Alt Right, in both its extreme and moderate forms, has been subject to criticism from both conventional conservatives and leftists in recent years. Thompson conveniently tars such thinkers with the Nietzschean brush, though his diatribe evinces little or no understanding of the Nietzschean critique of Enlightenment ideals, nor does he acknowledge the role of satire and deliberate exaggeration in the writings of Alt Right bloggers—techniques borrowed partly from Nietzsche himself and from Soviet-era samizdat writers.

In a defense of his own work published in an earlier issue of The American Mind (Oct. 2019), the Bronze Age Pervert states that Bronze Age Mindset was not written as a political manifesto but in a “mood of revelry and laughter.” The mainstream media, he writes, adopt “humorlessness as a strategy and pretend to see policy proposals when we engage in fun and trolling.” His attacks on the principle of equality should be understood in this light. The Pervert freely acknowledges that the Founders did not promote “absolute equality,” but that is precisely what is promoted by the regnant liberal regime.

What is often missed in critiques of the Alt Right is an honest assessment of those thinkers whom the Alt Right have appropriated for their use. Among these thinkers, Nietzsche is one of the most prominent, to be sure. All too often Nietzsche’s work has been read as giving birth to genocidal racism and anti-Semitism. He is still regarded by some, though this notion has been thoroughly debunked, as a forerunner of National Socialism.

Descended from a line of Lutheran pastors, Nietzsche became a classical philologist at the University of Basil, but would later become, like the Plato whom he despised, an itinerant philosopher.

Nietzsche’s study of the classics fueled an interest in pre-Socratic Greece, including the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers as well as the Mycenaean world of Homer. In Nietzsche’s reading, this world was much more vital, irrational, and impulsive than the allegedly boring and vacuous world of Plato’s Academy, in which any genuine human vitality was stifled by “theoretic” reason—a hyperrational denial of the healthy instincts of the body. Figures like Achilles and Dionysian ritual practices were embodiments of a truly natural life.

For Nietzsche, the Socrates of the Platonic dialogues was a creature of ressentiment who had his head in the clouds, as Aristophanes famously depicted him. In Nietzsche’s view, this Socratic tradition was later amplified by Hellenistic Judaism and then Christianity, eventually resulting in the lifeless, weak, and unnatural world of the Enlightenment.

In order for Westerners to free themselves from this unnatural world, it was necessary for them to recognize the “idols” or illusory products of “all too human” universal reason that, by Nietzsche’s day, had resulted in an ever-increasing uniformity and rationalization in culture and politics, including Kantian arguments for the preeminence of the nation-state as the culminating achievement of historical progress.

Such a civilization was becoming, in Nietzsche’s view, what Max Weber later called an “iron cage,” a construct promoting mindless conformity, regimentation, and suppression of genuine individuality. A great defender of particularity, Nietzsche saw the nation-state as a destroyer of any diversity worth the name. As for socialism, he saw it as a form of despotism engaged in a “fundamental remolding…and abolition of the individual.”

None of this is to deny that Nietzsche was a troubling and dangerous thinker, one who glorified the concept of the Übermensch and exulted, at least rhetorically, in the natural brutality of superior men. He saw the whole of Christianity as a manifestation of ressentiment—that is, the resentment of the weak for the strong—and never hesitated to celebrate radical inequalities. One can easily see how such ideas would be attractive to self-styled online intellectual “pirates” like the Bronze Age Pervert. But at least the Pervert and his dissident comrades recognize, more deeply perhaps than Thompson and his Straussian friends, that we are today living in Nietzsche’s nightmare, a world in which absolute equality is promoted relentlessly, while natural distinctions are ruthlessly erased.

As Max Scheler notes in his 1913 book Ressentiment, Christianity traditionally has not been a religion of cowardice and fragility, contrary to Nietzsche’s critique. Scheler, a convert to Catholicism, further argues that some (but not all) of Nietzsche’s critiques of the domestication and shallowness of certain elements of Enlightenment thought are not entirely off the mark. What is needed, Scheler argues, is for Nietzsche’s readers to approach his work with an educated and critical eye, to separate, as it were, the wheat from the nihilistic chaff.

As opposed to consuming Nietzsche wholesale or rejecting him outright, this nuanced method is the approach that thinking conservatives should take to reading both Nietzsche’s work and that of the postmodern thinkers he influenced. Such a careful reading will help conservatives diagnose the essential crisis at the heart of contemporary politics: the replacement of metaphysics with the will to power.

But this approach might accomplish something else. It would teach us to appreciate Nietzsche’s extensive critique of the cult of equality, the politics of misplaced pity (such as sympathy for, if not even promotion of, aberrant behavior) and much else that is wrong with contemporary society, including the radical direction taken by feminism. Nietzsche was a pioneer in addressing these current problems, and as a social critic he is still worth studying.

Nietzsche’s polemical style is mirrored in one of his staunchest critics, the ethicist Alasdair MacIntyre. In making the case for communally-based ethics, MacIntyre famously pits Nietzsche, the will-driven inventor of the new morality, against Aristotle, the ethical traditionalist and social organicist. Nietzsche had pioneered this tactic himself, contrasting the supposedly facile rationalist Socrates to the pre-Socratics and the authors of Greek tragedy. Nietzsche’s condescending treatment of Socrates, the father of the philosophical dialogue, is an argumentative ploy similar to MacIntyre’s later use of Nietzsche in After Virtue.

Whether we end up agreeing with Nietzsche the philosopher as opposed to Nietzsche the social critic, clearly there is more in his work than the facile critics of our “pajama-boy Nietzscheans” might imagine.

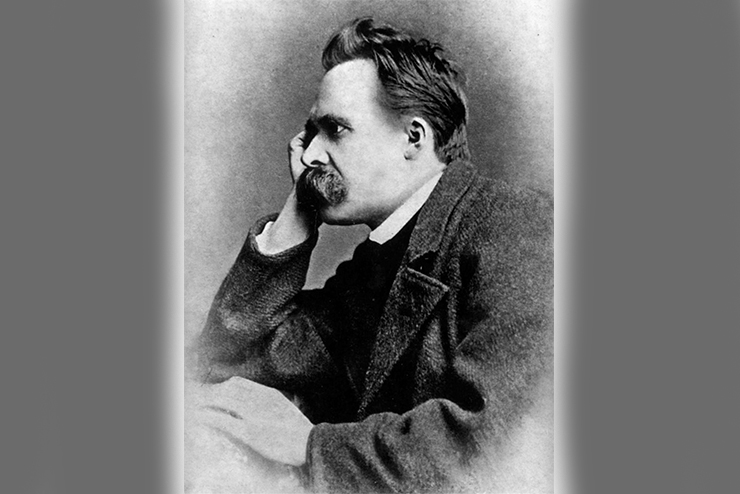

Image Credit:

above: portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche, 1882, by photographer Gustav Schultze, Naumburg (public domain)

Leave a Reply