“Is it time to reread Brave New World?” asks the distinguished historian Anthony Beevor, in a recent article on Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election. I think it is.

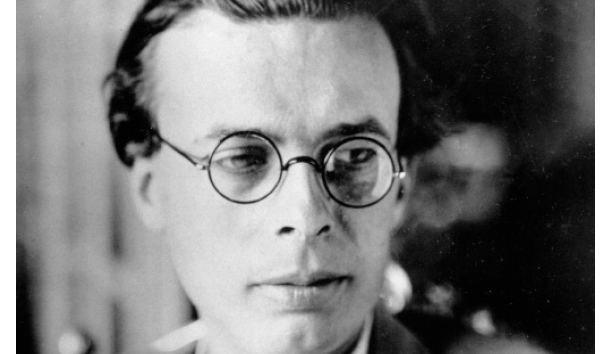

Of the two great fictional casts into the future, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), Huxley’s imaginative prophecies look ever nearer. Orwell’s dark vision of the Thought Police and the Ministry of Truth is well recognizable today, but Huxley cut deep with his insights into the society of the future. He is at least by implication as pessimistic as Orwell. Brave New World—the phrase is Miranda’s in The Tempest—is set 600 years into a future whose period is After Ford. There has been a great war, and the world is at peace. England is governed by the Resident Controller of Western Europe, Mustapha Mond (a deeply significant name). History, the past, has been abolished following Ford’s great doctrine, “History is bunk.” The only language is English, all others including French and German being “dead.” The Bible is unobtainable save in the Controller’s private pornographic-books collection. People are made content by social arrangements based on the drug “soma,” which has no harmful side effects and is universally recommended as the answer to all physical and emotional problems. Marriage does not exist; the words father and mother are smut. People are encouraged to be sexually promiscuous, and offspring are produced by test-tube methods. Families, in our own sense, do not exist. Neither do patronymics: People are named after the major figures of the Russian revolution. A central figure is Bernard Marx, and his lover is Lenina Crowne. A child is applauded for her “very good name,” Polly Trotsky. A rigorous Malthusian drill ensures that contraception is totally efficient, and most Alpha females are freemartins anyway. In the vocabulary of the A.F. society, viviparous is an obscene word that civilized folk do not employ. This coarse practice still exists on the Reservations, where savages live lives of squalor in the old ways.

A good deal of this is close enough to the sexual and drug-taking mores of today: Huxley was thinking along lines that are boulevards to the future. He saw the decline of support for marriage. (A recent writer remarks that young women do not really want marriage; they want the wedding.) Drug-taking is widespread at all social levels. It is not the more obvious parallels but the social discriminations and layerings of Huxley’s prophecies that are most critical now, and I think increasingly controversial.

“We decant our babies as socialized human beings, as Alphas or Epsilons, as future sewage workers or future . . . Directors of Hatcheries,” says the Director. When very young, the children are instructed through sleep-teaching, or “hypnopedia.” One lecture, received here by the Beta children, is Elementary Class Consciousness:

At the end of the room a loud speaker projected from the wall. The Director walked up to it and pressed a switch.

“ . . . all wear green,” said a soft but very distinct voice, beginning in the middle of a sentence, “and Delta Children wear khaki. Oh no, I don’t want to play with Delta children. And Epsilons are still worse. They’re too stupid to be able to read or write. Besides they wear black, which is such a beastly colour. I’m so glad I’m a Beta.”

There was a pause; then the voice began again.

“Alpha children wear grey. They work much harder than we do, because they’re so frightfully clever. I’m really awfully glad I’m a Beta, because I don’t work so hard. And then we are much better than the Gammas and Deltas. Gammas are stupid. They all wear green, and Delta children wear khaki. Oh no, I don’t want to play with Delta children. And Epsilons are still worse. They’re too stupid to be able . . . ”

The class stratifications are delineated as forcefully as in a Victorian minor public school, and the clear lesson emerges: Know your place.

But then the language of class has already been infiltrated by caste. As early as page 28, Huxley refers to the khaki-clad—“their caste was Delta.” This usage becomes steadily more prominent. Height matters: The lower orders “had been to some extent conditioned to associate corporeal mass with social superiority,” and elsewhere, “smallness was so horribly and typically low-caste.” (The records of the British Army in the two world wars fully bear out this perception: The average height difference between officers and men was four inches.) One of the characters, tall, handsome, and dominant, looked “every centimetre an alpha-plus.” Information comes to the masses from the three great London newspapers: The Hourly Radio, an upper-caste sheet; the pale-green Gamma Gazette; and, on khaki paper and in words exclusively of one syllable, The Delta Mirror. Caste is color-coded, and not just in clothing.

The social engineering of this world connects caste with ethnicity. On the Reservation, the Warden’s staff has “an Epsilon-plus negro porter.” The helicopter pilot is a Gamma, “a green-uniformed octoroon.” The menial staff at the Park Lane Hospital for the Dying are Deltas, the men, twins, having long, narrow heads (“dolichocephalic”), and the women, also twins, whose face was “a hairless and freckled moon haloed in orange.” The smaller houses by the Golf Club buildings are reserved for Alpha and Beta members, and are separated by a dividing wall from the huge lower-caste barracks. The workforce is severely graded by caste and ethnicity.

All this leads to Mustapha Mond’s overview of the system. It becomes a debate between the Controller and the Savage, the young man who has been brought into civilization from the Reservation. While living there he has found an old copy of Shakespeare’s works, which he quotes throughout his stay and which is the leitmotif of traditional values. The Controller also knows his Shakespeare, to the Savage’s surprise: “I’m one of the very few. It’s prohibited, you see. But as I make the laws here, I can also break them. With impunity.” Othello is the test case, on which the Controller comments, ‘You can’t make tragedies without social instability.” That stability is the highest achievement of the system: “People are happy; they get what they want, and they never want what they can’t get.” They are entertained with virtual-reality-style “Feelies” (one includes a love scene on a bearskin rug, every hair of the bear reproduced), soothed by soma, undisturbed by passion or relatives. “Orgy-porgy, Ford and fun” is the chorus in their post-Woodstock revels. And it is all based on social segregation. “The optimum population is modeled on the iceberg—eight-ninths below the water line, one-ninth above.” Only Alphas can do Alpha work, and only Epsilons could be content with the work they do. The occasional Alpha individualist rebelling against the system is exiled to an island (one of them, to the Falklands). The ultimate choice is between happiness and truth.

What are we to make of Huxley’s vision of the future? Clearly, he scored several direct hits, and some near misses. Some of it, plainly, does not seem to apply today. Class continues to make headway against caste, and a beautiful woman can always leap across the boundaries, with King Cophetua as the model: “Cophetua sware a royal oath, this beggar maid shall be my queen.” The mother of the future Queen of England started her career as an air hostess, and had later to endure scoffs of “doors to manual.” Nutrition has evened out the height of the population. Successful entertainers and sportsmen have entrée to the higher orders. And yet the suspicion grows that caste has not disappeared, but merely mutated into inequality. Stage and television have growing numbers of names that recall illustrious predecessors—their parents gave them the start. Oscar-heading actors come out of Eton, to the dismay of fellow actors who recall the 1950’s and the first wave of proletarian success on the stage. (In Huxley, Eton itself “is reserved exclusively for upper-caste boys and girls,” says the Provost.)

There is in this nothing new. For centuries the aristocracy has solicited employment for its family, and those well placed socially do the same today. Still, it looks as though the victories of Brexit and the U.S. presidency were born out of a widespread conviction that the ruling caste, without changing the rules, were doing rather too well out of them. Brexit was a nationalist uprising, and Trump’s victory—“Make America Great Again”—of the same order. The supranational elite is now having its assumptions challenged, with the masses in both countries having shown that they are deeply unhappy with the decisions of the Alpha-pluses. Today’s Establishment has evidently adopted the Controller’s view of society, that the top ninth do the thinking, the decisionmaking, the self-rewarding. That goes for the code of law, which “is dictated, in the last resort, by the people who organize society.” I should be surprised to learn that today’s Alpha-plus caste does not accept the main lines of Huxley’s vision. They will have to handle the growing issue of workforce robotization, perhaps the keenest challenge to the status quo.

Huxley did not pose an argument so much as a question. Here in 2017, I answer that the tension between class and caste is not settled, and has yet to be reset.

Leave a Reply